From time to time you come across a paper that blows you away with the amount of work it must have needed to create it and the fascinating insights that can be gleaned from it. For me the preprint “All Crises are Unhappy in their Own Way: The role of societal instability in shaping the past” by Hoyer et al. (2024) is such a piece of work. They have built a new dataset on top of the Seshat history database (Turchin et al., 2019) (1). Their new data is meant to capture the majority of big crises from the beginning of recorded history until around the beginning of the 20th century. They use this dataset to try to prove or disprove a large group of history’s big narratives in one big swoop.

The grand narratives of history

When we talk about the history of our species, often grand narratives are used. These try to explain why history happens or what major trends we can see developing from the deep past to today. Some famous examples include:

- Steven Pinker’s argument that violence has been decreasing for millennia and that we are living in the most peaceful time since humanity exists.

- Joseph Tainter’s theory of diminishing returns of complexity, which we discussed in more detail in an earlier post. The complexity view of collapse proposes that societies become increasingly unsustainable as solutions to problems create a burden of maintaining that complexity.

- Peter Turchin’s secular cycles, also described in an earlier post. Secular cycles assume societies rise and fall through phases of cooperation fueled by growth turning to competition due to resource limitations.

Other examples, which cannot be attributed to a specific person:

- The major world religions exist to provide a social glue that makes interaction of individuals outside of their direct kin possible. This (allegedly) leads to less crises in regions where the majority of people belong to one of the major world religions.

- Over time societies built institutions, which allow them to control crises better.

- Greater crises lead to greater transformations and reforms.

Hoyer and co-authors think that all of those are potentially the product of cherry picking. We therefore need a big dataset, which contains as many crises as possible, as well as events that could have become a major crisis, but didn’t.

How to build a gigantic crises dataset

To create a big dataset about crises, you first have to define what you mean when you are talking about crises. The definition used by Hoyer et al. is:

“We define crisis as a period of high societal stress and risk of systemic dysfunction - in effect, times when signs of unrest, institutional failing or decline, and/or socio-political instability appear on the rise compared to previous generations (until roughly 50 years earlier).”

They acknowledge that crisis is not the best word for this as it is more concerned with the time before, after and during what we usually see as a crisis, but think that we don’t have any better, so they stick with it. To clarify what counts as a crisis, here are some examples:

- The times of troubles in Russia

- The French Revolution

- Fragmentation of the Mughal Empire

- Meiji Restoration in Japan

To find all the actual and potential crises, they talked to a large group of historical experts and read everything they could find in the literature that could give them hints. They end up with 250 cases, from which they used 168 in their final analysis, as the rest did not have enough data available to be reliable. Scale wise, these entries could relate to everything from a city state to a global empire. To group these things together, they use the term polity (2). The dataset contains samples from all over the world and covers everything between the Bronze Age and the early 20th century. It is somewhat skewed to more modern crises, as we have more data available. For each of those samples they collected a wide array of data:

- Crisis outcomes: Does the crisis result in a civil war, a revolution, etc? As the crisis definition is trying to capture a broad period of time, these crisis outcomes do not necessarily have to be the endpoint of a crisis.

- Crisis intensity: This includes factors like how much the population declined, if the elite lost their positions, assassinations of rulers, if the state remained intact or was partially or completely dismantled. They then sum those all up to give every crisis a turmoil score.

- Reform: How much the state reformed after the crisis. This focuses on reforms which improved things like well-being and freedom. For example, expansion of suffrage or major public goods programs.

- Polity metadata: Things like duration of the crisis, lifespan of the polity, geography, religion.

- Societal complexity: The overall complexity of the polity. This includes things like scale (territorial extent, population, …), hierarchical complexity (how many levels your hierarchy has in admin, military and religion), governance (how professional and standardized your bureaucracy is), infrastructure, informational complexity (is writing present, how did you keep your records, …), money (what kind of money you used). The overall complexity is then represented as the first principal component of all these measures.

An overview of past crises

Based on this massive dataset, Hoyer et al. do a wide variety of analysis with the data. This is mostly simple correlations and descriptive statistics, so I think with more powerful tools, there are likely a lot of other insights to be gleaned from this data. But even with such simple approaches, they provide a lot of fascinating results.

There is no typical crisis

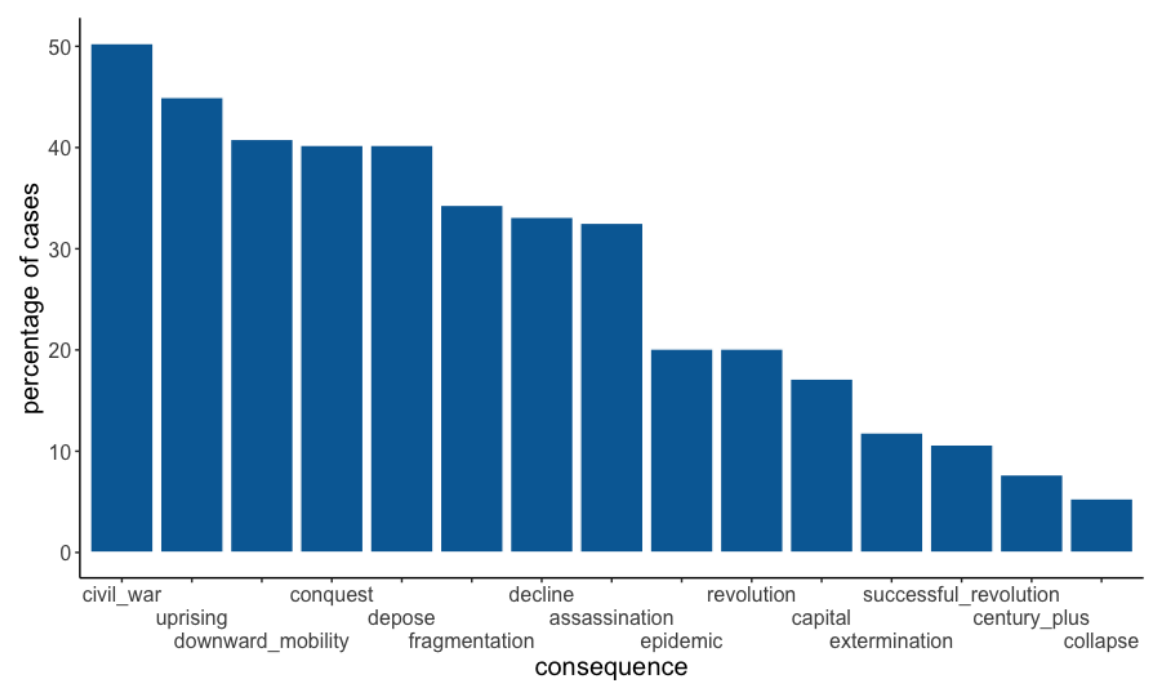

All crises tend to be somewhat unique and they differ a lot in their properties. While the median duration of a crisis is 22 years, the range is between < 1 year and 200+ years. There is also no typical outcome of a crisis. While around 50% of the crises end in some kind of civil war, there are a lot of other outcomes which can also also be observed (Figure 1). These outcomes are also often combined and a crisis can have a variety of different outcomes at once. Quite relevant to this living literature review, only around 5 % of crises result in some kind of collapse.

Figure 1: Consequences of crises and their occurance rate

Crisis intensity and subsequent reforms do not correlate

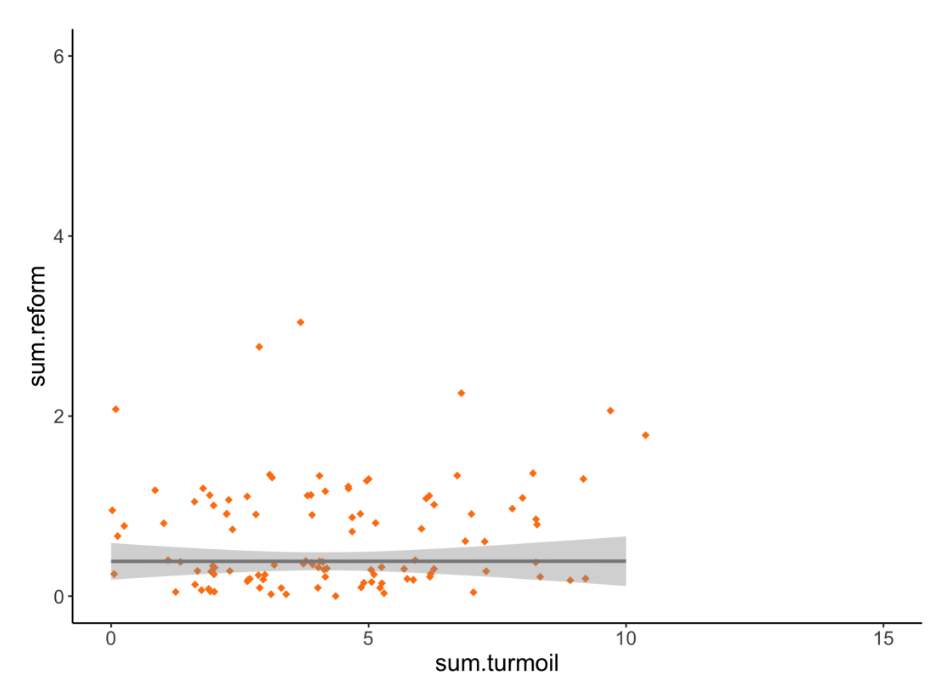

The distribution of crisis intensity and the extent of reforms are quite different. While the intensity of the crises seems to roughly follow a normal distribution (3), the distribution of the extent of reforms centers around 0, meaning that for the large majority of crises no reforms were conducted afterwards. These differences even become more striking if you directly compare those two distributions (Figure 2). This dataset does show that, conditional on a crisis happening, a bigger crisis does not tend to lead to bigger reforms.

Figure 2: Correlation of the amount of reforms and the intensity of the crises (The numbers are actually integers, but they added some noise, so you can more easily separate the individual points visually).

Crisis dynamics

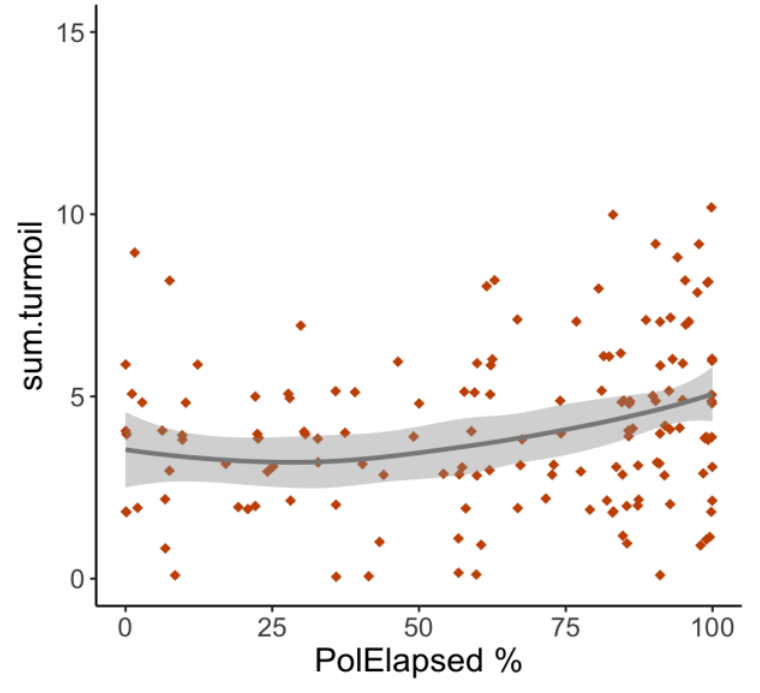

In addition to their severity and outcomes, crises can be characterized by various other factors. Notably, the severity of crises has not diminished over time; significant crises were as likely in 1850 as they were in 1000 BC. This finding appears to be fairly robust. The data may be skewed towards recent crises, but we should anticipate that the crises in a deeper past should be more severe to even make it into the historical record. If there is any trend in the data, it is that crises in the last thousand years have been somewhat more severe compared to earlier periods. However, there appears to be a correlation with the life cycle of a polity. Analysis of crisis distribution within a polity’s lifespan reveals that crises in the latter half tend to be marginally more severe (Figure 3). Despite this, the likelihood of reforms remains relatively constant throughout a polity’s lifetime. This same figure contains both alarming and hopeful insights: while civilizations can endure major crises and persist for long periods thereafter, even minor crises have the potential to bring about their end.

Figure 3: Severity of crises over the lifetime of a polity.

The level of crisis turmoil appears to be independent of world region, suggesting that geographical location does not significantly impact the severity of crises experienced. Additionally, regions where world religions constitute the majority faith tend to undergo slightly less severe crises. Moreover, larger crises are more likely to result in state-related outcomes (meaning things like being conquered by a rival or having a civil war), with population decline being also slightly correlated with crisis intensity.

State Characteristics and Reform

As stated above the extent of reforms does not correlate at all with crisis severity. However, there are a variety of other factors that increase or decrease the level of reforms. One important factor is revolution (4). If a revolution happened, in 65% of the cases reforms followed, while if no revolution happened, reform only followed in 23% of the cases. Interestingly, even in the revolution subset of the data, there is no correlation between crisis severity and number of reforms. This seems to indicate that revolutions make reforms more likely, even if the revolution did not lead to any major crisis afterwards. However, assessing reforms here is quite complex. Reforms may also follow a regime change.

The administrative complexity of a state is another important factor. Higher administrative complexity tends to hinder reform efforts, with the idea being that the intricacies of highly specialized bureaucratic systems can impede the implementation of new policies and structures. Conversely, polities with smaller geographical size and lower administrative complexity show more reforms. Possibly because they allow for more streamlined decision-making processes and thus easier implementation of changes.

Finally, the overall hierarchical structure of a state plays a role in determining its openness for reform. While an increased number of hierarchical levels within a state typically correlates with higher rates of reform, this trend is contingent upon the hierarchy not being predominantly situated within the administrative apparatus of the state. Or in other words, if you have parallel power structures in a state, this seems to make it easier to enact reforms. Interestingly, the complexity of the different hierarchies tend to correlate very highly with each other. This indicates that there is some kind of sweet spot in hierarchy and the distribution of power in a polity that allows easier reforms.

Which historical narratives hold up?

Violence has decreased over human history (Steven Pinker)

Hoyer and coauthor’s data does not support Pinker’s claim that violence has declined over the long run: the severity of crises has not decreased over time. If anything it has increased in the last 1000 years. However, it’s important to note that Pinker focuses primarily on the decline in the number of violent deaths over time, whereas the dataset presented here examines the intensity of crisis periods and also includes some crises caused by natural disasters. Therefore, Pinker’s hypothesis may still hold true, but must be qualified with the acknowledgment that it may not necessarily indicate a more peaceful era overall, but rather only a decrease in violent deaths amid ongoing crises.

Complexity has diminishing returns (Joseph Tainter)

The findings from Hoyer and colleagues do not invalidate the theory of diminishing returns of complexity. Tainter’s theory suggests that as a society progresses, its resilience diminishes due to the increasing resources needed to maintain solutions to previously resolved societal issues. The data presented here, (Figure 3) aligns with this theory by demonstrating a rise in crisis severity over the lifespan of a polity. However, the strength of this trend is relatively weak, which creates some inconsistency with research on societal longevity, discussed in a previous post, indicating a clear trend of increased collapse likelihood with polity age. Nevertheless, this shows that the complexity theory has stood strong against two independent attempts to falsify it with quantitative data.

Secular cycles (Peter Turchin)

The idea of secular cycles or any cyclical approach to history cannot be validated with the data here. If the secular cycles idea holds true, we should expect that polities end with a major crisis event. This does not seem to be the case here, which makes this hypothesis less likely to be true.

Religions as social glue

This hypothesis seems to be true, but only to a small extent. The major religions seem to make crises less severe, but only by a small amount.

Building institutions helps to survive crises

The question if this historical narrative is true is a bit more difficult to answer. We already discussed in a previous post that more state capacity seems to be important to make it through a crisis. Such an argument is also echoed by Hoyter et al.. Still, their study also shows that too much bureaucracy is also not helpful and that parallel hierarchies make reforms more likely. To me this seems to indicate that somewhere in the space of hierarchies and state capacity there is a somewhat optimal range for reform and resilience, but from the paper it does not become clear where exactly this range might be.

Greater crises lead to greater transformation.

This historical idea seems the most clearly false under Hoyer and colleagues data. There is no indication that bigger crises lead to bigger transformation. Even if you look at revolutions, which lead to more reforms, the size of the crisis is not correlated to how many reforms are enacted afterwards.

Why are some crises worse than others and why do some crises lead to reform?

The answer is somewhat beyond the scope of the paper, but Hoyer and coauthors still discuss some potential explanations of why this might be happening:

- The size of the external shock: Many crises are caused by events outside of the influence of the polity. For example, a large-scale drought (5) could push a society beyond its breaking point even if it is well prepared.

- Elite behavior: The response of elites varies significantly even to similar crises. Hoyer et al. illustrate this with the case of the Black Death and how elites in both Egypt and England reacted differently. In England, the crisis prompted wealth redistribution and the advancement of workers’ rights, contributing in part to the onset of the industrial revolution. Conversely, in Egypt, the crisis was poorly managed, resulting mainly in increased repression and no redistribution of wealth. This highlights the question of whether elites are capable of equitably distributing the costs of crises across society, rather than placing the burden solely on the less well off.

- State capacity: As mentioned above, the more state capacity you have the more you can prepare for crises and the quicker you can move resources once the crisis happens. However, you have to manage at the same time that the state is not made inflexible by an overly complex bureaucracy.

- Revolutions: One of the most fascinating results of this study is that revolutions seem to be one of the major drivers of reform. However, as there is no connection to the size of the crises, this seems to imply that the best way to push for reforms is to make a revolution, but somehow manage to keep the revolution under control, so it does not spiral into big turmoil.

Conclusion

As with all good pieces of science, this paper opens up at least as many new questions as it answers old ones. However, it tries to give answers to an impressive amount of questions. Not all of them have been answered, but still this paper presents a lot of compelling evidence for them. This highlights the power of quantitative history, while also showcasing the massive amount of work that has to go into it to make it happen. This paper builds on the work of hundreds or even thousands of other researchers. I hope such research continues to be funded and produced. Especially, as the team around Hoyer also plans to extend the timeline of the dataset until today. Not only would this give even more accurate answers to the questions discussed here, it would also provide a pretty strong datapoint to the question if history in the last ~100-200 years is a continuation of past trends or is something new that cannot be compared to earlier history (6).

Endnotes

(1) A vast historical dataset, which we have already mentioned a bunch of times on this blog: 1, 2, 3, 4

(2) Which they define as: “We define a polity as an independent political unit which can range from villages (local communities) through simple and complex chiefdoms to states and empires.”

(3) You can also make a good argument that this is not really a normal distribution, as we might be undersampling very minor crises. If almost nothing happened, there is a bigger chance that it was not recorded and therefore is not present in the dataset.

(4) Revolution here is defined as: “Revolution is the attempted forcible overthrow of a government through mass mobilization (whether military or civilian or both) to create new political institutions. This is distinct from rebellions and other uprisings that do not necessarily involve mass mobilization or seek systemic / governmental change (though they can)”

(5) We discussed in earlier posts how such climatic shocks can spiral out of control: 1, 2

(6) This question was also discussed in an earlier post.

How to cite

Jehn, F. U. (2024, April 9). What factors allow societies to survive a crisis?. Existential Crunch. https://doi.org/10.59350/qk98g-z9j18

References

- Hoyer, D., Holder, S., Bennett, J. S., François, P., Whitehouse, H., Covey, A., Feinman, G., Korotayev, A., Vustiuzhanin, V., Preiser-Kapeller, J., Bard, K., Levine, J., Reddish, J., Orlandi, G., Ainsworth, R., & Turchin, P. (2024). All Crises are Unhappy in their Own Way: The role of societal instability in shaping the past. OSF. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/rk4gd

- Turchin, P., Whitehouse, H., Francois, P., Hoyer, D., Alves, A., Baines, J., Baker, D., Bartkowiak, M., Bates, J., Bennett, J., Bidmead, J., Bol, P., Ceccarelli, A., Christakis, K., Christian, D., Covey, A., De Angelis, F., Earle, T., Edwards, N., & Xie, L. (2019). An Introduction to Seshat: Global History Databank. Journal of Cognitive Historiography, 5. https://doi.org/10.1558/jch.39395