One explanation for collapse is just bad luck. Sometimes all the factors that influence your society just point in the wrong direction and your empire crumbles without you being able to stop it. I want to use this post to explore if bad luck is a helpful framing for societal collapse.

How common is the back luck view of societal collapse?

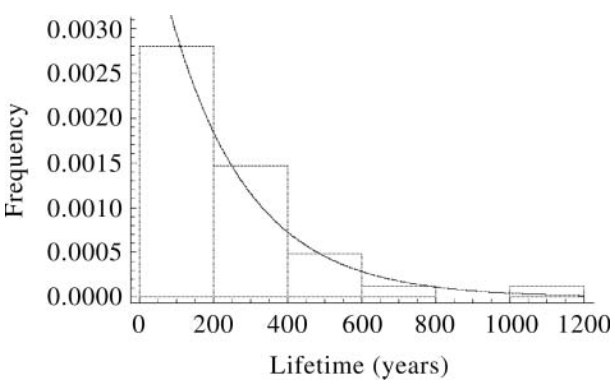

One of the earlier sources that discusses this explicitly is a short paper by Samuel Arbesman (Arbesman, 2011). This paper seems to be the first analysis of how long empires last in general (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Frequency distribution of the lifetimes of empires (Arbesman, 2011)

Arbesman simply plotted the lifetime of empires and used an exponential decay to fit the resulting data. He shows that it seems that the lifetime follows an exponential decay, which implies that civilizations just get randomly knocked out. Arbesman notes this, but also offers some explanations why this might not be random after all. His most prominent explanation is the Red Queen Effect. This is a cultural reference to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, in which Alice encounters the red queen who tells her: “Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.” Translated to our topic here this means that societies are faced with a changing environment, which continuously demands new adaptations from them. They implement these adaptations, but this only gives them a brief pause as new challenges keep popping up. This results in a constant rate of societal collapse.

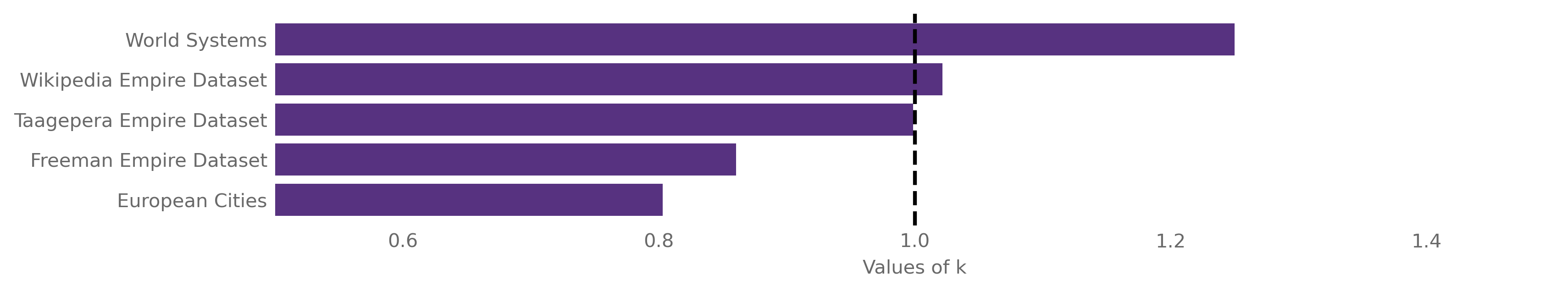

A similar, but more extensive analysis has recently been published by Anders Sandberg (Sandberg, 2023). Like Arbesman, Sandberg tries to fit the lifetime of civilizations to a given distribution. However, in contrast to Arbesman he uses five different datasets, as well as using a Weibull instead of an exponential distribution. The mathematics are not important for the post here, but the fit of the parameter k can be used to make an assessment of the hazard rate a civilization is exposed to, meaning how big is the chance each year of the civilization collapsing. A value of 1 means a constant rate, a value above 1 means an increasing rate, while a value below 1 means a decreasing rate. Sandberg finds a variety of values for k (Figure 2), which seem to center around a value of k = 1. From this he concludes that civilizations likely experience a static hazard rate over time.

Figure 2: Summary plot for the values found by Sandberg for k for the fit of the Weibull distribution. k = 1 → constant hazard rate

To further classify his results, Sandberg compares these findings to a variety of other complex systems and their hazard rate. For instance, he uses a dataset of software lifecycles and finds k = 1.7353, implying that software experiences a very steeply increasing hazard rate over time. Firms on the other hand have a k-value near 1, making them more similar to states.

The explanation Sandberg offers for this is also very similar to the one of Arbesman and also refers to the Red Queen Effect. He argues that civilizations constantly have to adapt to arising challenges, which results in a static hazard rate over time. However, he also thinks that societies likely cannot simply increase their preparations against collapse indefinitely, as every added bit of security has a slightly larger cost than the one before. Therefore, if you have a constant hazard rate, it is only a question of time until your civilization collapses.

To tackle the problem of a constant hazard rate he argues that one solution would be to decouple parts of our society, so that a local collapse would not affect the whole. However, Sandberg thinks this would be hard to do. While this is likely true, there are also movements like Degrowth who want to do exactly that.

Criticism of the bad luck idea

It is interesting to note that so far I have not yet read a paper that discusses bad luck as a helpful explanation of collapse which is written by an actual historian. The scientists who champion these kinds of ideas seem to be mostly coming from physics, economics, computer science and similar fields. Which intuitively makes sense to me, as those are all fields that have a stronger held belief that complex phenomena can be quantified in neat equations. So, why shouldn’t societal collapse be one of them?

A more critical view comes from Joseph Tainter, who is both a historian and has been well known for his work on societal collapse for decades (Tainter, 2023) (1). Tainter’s literature review is not specifically focussed on bad luck, but asks the more general question of how scholars have explained collapse over time. One thing he notes is that societal collapse explanations seem to follow trends, like the rise of ecological explanations after the publication of the Limits to Growth report. After giving an overview of collapse research similar to the first post in this series, Tainter moves on to highlight two earlier studies, which he sees as the only ones that covered collapse in a sufficient breadth. The first one is by himself (Tainter, 1988) and the other one is a book by Guy Middleton (Middleton, 2017). He singles these two studies out, as they summarized all known explanations for collapse for 19 civilizations. Those sum up to 64 explanations in total. The most favored explanations seem to be external conflict (12), internal conflict (11) and climate change (10). However, Tainter also notes that this identified that 28 of the 64 explanations frame the collapse as a sudden and unexpected event caused by climate change, invaders, catastrophes or a chance concatenation of events. He sees this as a lacking explanation, as it ignores the complicated path that led to the event having the chance to cause a collapse.

A recent paper by Scheffer et al. (2023) also improved upon the analysis of Sandberg and Arbesman and showed that bad luck is likely an insufficient explanation of collapse. Just as the studies by Arbesman and Sandberg, Scheffer and co-authors used a large dataset of the life cycles of past civilizations and then looked at which probability distribution produces the best fit. However, Scheffer and coauthors did not rely on existing datasets, but instead created their own (2). This allowed them to both collect a larger sample and make sure that they only included those data points which they deemed of high enough quality. They made sure that they only included those data points where they could clearly point to a beginning and end of a given state. In addition to creating their own dataset, they also reproduced their own analysis using data from the SESHAT database. In both cases the results were very similar. They found that the risk of collapse increases for the first ~ 200 years of the state’s existence and levels off after that. This implies that either risk rises over time, resilience declines or both. To determine which it is, they propose that future research should look at past societies and see if they find critical slowing down in their response to disturbances (3). Critical slowing down means that a system takes longer to recover from a disturbance, the closer it comes to a tipping point due to decreased resilience. They also highlight some other studies who have already tried something in this direction. Their results seem to imply that critical slowing down is happening before collapse, but we need more and better data to be sure.

What can we learn from the bad luck idea of collapse?

I think it is right to say that civilizations are destroyed by bad luck, but only in the same way my own death can be explained by bad luck. I can’t know when I will die, but if I look over all humans that have lived in the last 100 years, I will get a pretty clear picture of when I can expect to leave this world. The same is likely true for civilization. It will always be difficult to exactly know what the cause will be that ends a civilization, but this does not mean that all ends are equally likely. We can still look at past civilizations and try to understand what happened, so we can prepare for more likely causes and understand the warning signs, which earlier societies might not have seen. However, we also have to think about how transferable our insights of the past are. Maybe bad luck was a better explanation in the past, but has ceased to be so, as our society today mostly faces dangers from its own making?

This means that framing civilizational collapse as just bad luck is not really that helpful, as it is not really telling us much except the end result of collapse. However, what we really want is to understand the gears. This is at least partially done in the bad luck paper by Anders Sandberg, where he shows us across many examples that civilizations seem to face a stable risk of collapse. While this does not help us in understanding what ultimately destroyed the civilization, it does give us some evidence that historical theories that predict an increasing chance of collapse are less likely (4). Approaches like the one by Sandberg could also be framed as giving us a base rate of societal collapse. They are helpful to give a range of plausible outcomes, but will not be able to give detailed explanations for societal collapse.

This is also related to the framing of seeing risk as a combination of hazard, vulnerability and exposure (as explained in this earlier post). If I separate the risk in those categories, framing it as bad luck does not really work, as it highlights that risk is actually a continued interaction of how we understand the risk and how we prepare for it. If a hazard is able to create damage, it is not bad luck, but failure of our preparation which left us vulnerable and exposed.

Seen in such a light, attributing societal collapse just to bad luck really is a insufficient explanation of why civilizations collapse or to quote Joseph Tainter here:

“After 3,000 years of literature on collapse and related phenomena, we cannot fail to be disappointed that 44% of collapse explanations answer the question “What causes collapse?” with the reply “Nothing in particular, just bad luck.” Surely we can do better.”

Endnotes

(1) Interestingly, this is published in the same book as the analysis by Anders Sandberg (Patterson, 2023).

(2) They also attached the whole dataset as a supplement to their paper, which I think is a great practice and I wish more paper would make it so easy to reproduce their results.

(3) This critical slowing down is the same process which we discussed in the tipping points post.

(4) An example of such a theory is the idea that civilizations accumulate more and more complexity, which eats up their resources and makes them less able to react to catastrophe.

How to cite

Jehn, F. U. (2023, December 4). Is societal collapse just a random event?. Existential Crunch. https://doi.org/10.59350/jjsgz-g1t08

References

- Arbesman, S. (2011). The Life-Spans of Empires. Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History, 44(3), 127–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/01615440.2011.577733

- Middleton, G. D. (2017). Understanding Collapse: Ancient History and Modern Myths. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316584941

- Patterson, M. C., Peter Callahan, Paul Larcey, Thayer (Ed.). (2023). How Worlds Collapse: What History, Systems, and Complexity Can Teach Us About Our Modern World and Fragile Future. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003331384

- Sandberg, A. (2023). The Lifespan of Civilizations: Do Societies “Age,” or Is Collapse Just Bad Luck? In How Worlds Collapse. Routledge.

- Scheffer, M., van Nes, E. H., Kemp, L., Kohler, T. A., Lenton, T. M., & Xu, C. (2023). The vulnerability of aging states: A survival analysis across premodern societies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(48), e2218834120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2218834120

- Tainter, J. (1988). The Collapse of Complex Societies. Cambridge University Press.

- Tainter, J. A. (2023). How Scholars Explain Collapse. In How Worlds Collapse. Routledge.