If you read about collapse in past societies, one thing that comes up almost always is famine. Why is famine so closely connected with societal collapse? This post will summarize the reasons for this strong connection.

Famines have many triggers

To begin, the food system is very connected with many parts of our society. For example, we need a stable climate, a steady supply of fertilizers and pesticides, and transportation infrastructure to move the food from where it is grown to where it is needed. This interconnectedness means that many different kinds of events could impact the food system. One framework that highlights this well can be found in a paper by Avin et al. (2018). They used the existing planetary boundaries system (more information about planetary boundaries in the context of collapse can be found here) to identify which parts of human society are vulnerable to global catastrophes (for example nuclear war, asteroid impacts, and geoengineering). They classify the global catastrophes by the critical societal systems they interact with (e.g. the food system or global security) and what the spread mechanism of the catastrophe is (e.g. if it spreads by natural systems like air dispersal or more abstract networks like the digital infrastructure). They find that our food system is the one part of our society that is impacted by the largest amount of global catastrophes.

This is largely due to the food system’s dependence on a stable status quo. Food is continuously grown and needs a steady input of acceptable climate, fertilizers/pesticides to be grown and an intact trade system to be distributed. If any part of this chain is disrupted, food production suffers.

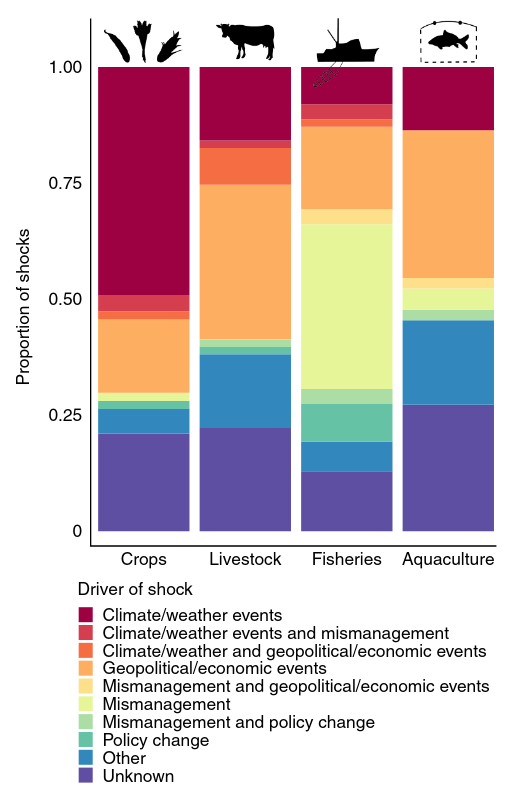

This description is relatively abstract. We can also look at more empirical assessment of how the food system is influenced by a lot of factors. A 2019 paper by Cottrell et al. looked at food production data for crops, livestock, fisheries and aquaculture and determined if a food shock happened in those areas in the years 1961 to 2013. They define a food shock as any event in their data where there is a negative break in the autocorrelation in the data and try to find a real world event that can explain this break. Autocorrelation is a statistical concept that measures how closely a data point is related to its past values. They find that food production shocks are happening more or less constantly, but only on a local level that averages out most of the time if you look at it globally. They find that the main reasons for those shocks are climate events (strongest for crops), geopolitical events (strongest for livestock and aquaculture) and mismanagement (strongest for fisheries) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Causes of food production shocks (Cottrell et al., 2019)

Famines are self-reinforcing

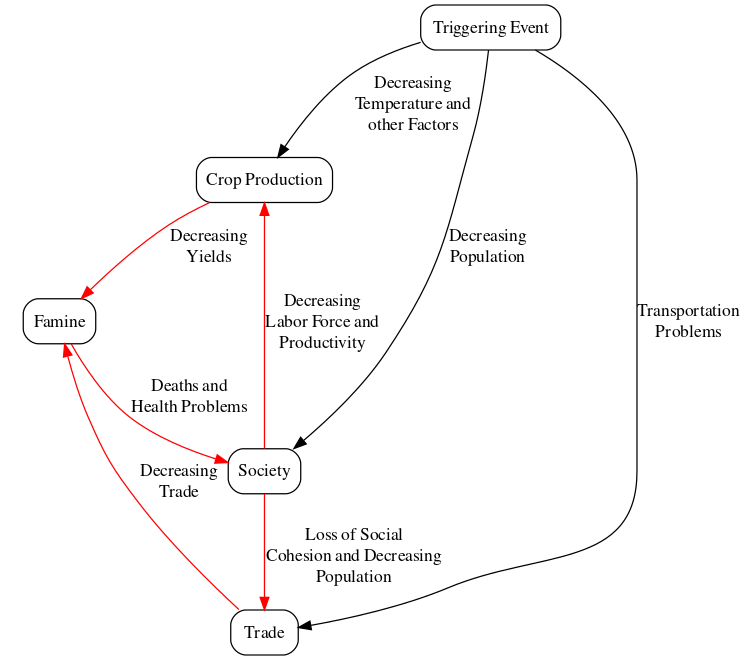

So there are a lot of ways to arrive at famine. But a second reason for the connection between famine and social collapse is that once you are in a famine it is difficult to get out of it again, as the famine tends to reinforce itself. Charalampopoulos & Droulia (2021) looked at historical famines and tried to come up with a simple model that captures the relationship between extreme weather events and famine. I adapted it from their paper (Figure 2) to a more general form, as their explanation seems to me like they are agnostic of what is the cause of the famine.

Figure 2: The self-reinforcing mechanism of famines (adapted from Charalampopoulos & Droulia (2021)). Red arrows indicate the self-reinforcing famine cycle.

The self-reinforcing cycle they describe originates with a triggering event, which can encompass various factors that create stress for a society. This can be a global catastrophic risk, but the concept applies broadly to any event that significantly diminishes food production or disrupts trade and can be local, regional or global. This triggering event operates through multiple pathways. Firstly, it can hinder crop production by creating adverse conditions for plant growth, such as reduced temperatures. Secondly, it leads to a reduction in the overall population of the society and thus decreases the pool of available labor. Lastly, it creates transportation challenges that hinder the efficient distribution of food. Should these effects reach a critical magnitude, they set in motion a self-reinforcing cycle:

- A society that experiences a substantial loss of population will inevitably see a decline in its capacity to both produce and trade food resources.

- Reduced food production and trade result in a decreased availability of food within the society.

- The scarcity of food leads to increased instances of famine, exacerbating the prevalence of deaths and health-related issues, thus initiating the subsequent iteration of the cycle.

This self-reinforcing cycle continues until one of two things happen: You get food from somewhere else or our local population and food production have found a new equilibrium. The first option was often not available in the past, as moving goods was comparatively expensive before we had fossil fuels and would not be available today if we faced a global catastrophe. The second option usually means that the new equilibrium is considerably lower than before. As the famine continues, the societal structures needed to produce a high amount of food crumble. The lowest equilibria is either smallholder farms or hunter gatherer tribes. Charalampopoulos & Droulia (2021) argue famines are comparable with major wars, when it comes to the destruction of social structures and population numbers. They also emphasize that famines usually happen in tandem with other disruptive events like war, migration, or revolution. This makes it even more difficult to stop the famine cycle.

Famines are hard to defend against

So lots of things can cause famines, and once they get started they can be hard to pull out of. But they’re also hard to protect against. Humans eat a lot of food and much of the food we have goes bad quickly, especially if it is not cooled. This means there is only a limited amount of food available at any given time.

It is difficult to estimate the global amount of food; it also varies over time, depending on the season. However, there are some rough estimates. Baum et al. (2015) did a literature review on what interventions could increase resilience to global food supply catastrophes and find that we can expect to have a leeway of 4-7 months of food supplies globally. They also argue that while food storages create some slack in the system they are not really the solution to bigger catastrophes. Food storage is very expensive. Creating and maintaining large food reserves increases the price of food globally, which makes more humans insecure in the present. Finally, many of the catastrophes that could lead to a global societal collapse would need food supplies for 5-15 years (for instance, nuclear winter, volcanic winter or impact winter). It could simply be near impossible to store such a gigantic amount of food safely for such a long time. This means that food storage can only ever contribute to food security, but not be the sole solution, especially for bigger catastrophes.

While storing food in advance of a famine is challenging (especially for multi-year global famines), this is not the only way countries can reduce their risk. It is notable that no stable democracy has yet experienced a famine (Hasell & Roser, 2013). More broadly, as discussed in this earlier post, participation and democracy have been found to enhance societal resilience.

Famine in interaction with climate and society

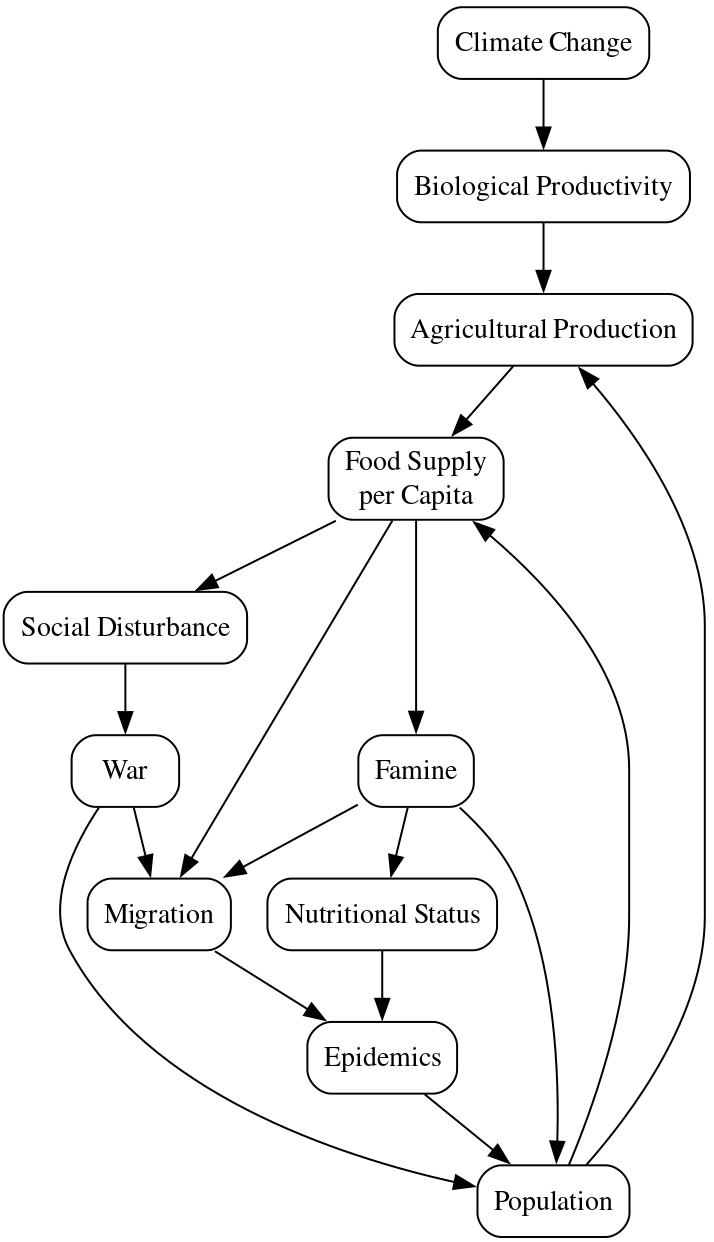

We can find all those complex interactions of famine with other parts of society when we look into history. Zhang et al. (2011) tried to determine the timing of famines, climate and other large scale human crises. To do so, they built a model that looked at the timing of climate shocks and how the resulting effects rippled through society (Figure 3). They then use empirical data and statistical analysis to determine the order in what climate shocks and the societal effects happen and if this follows their model.

Figure 3: Complex interaction of climatic shocks with famine, adapted from Zhang et al. (2011).

They find a mechanism that is quite similar to what we have described here so far and also the timing is correct. This means that you usually have the climate shock first, this reduces the amount of food you can produce, which in turn leads to famine, conflict and disease. This leads to population decline, which in turn changes both the amount of food needed and produced. Therefore the paper by Zhang and co-authors nicely ties together the origins of food shocks with the resulting consequences in an empirically validated model. More concrete examples on how such a cascade plays out in our history can be found in the post about the crisis following the potato famine, as well as the in-depth analysis of the Little Ice Age.

The model of Zhang et al. covers only the direct interactions from climate to declining population. However, if you really want to understand how things might play out it makes sense to include indirect processes as well. This massive project was undertaken by Richards et al. (2021). They built a causal-loop diagram (1) which includes the indirect effects of climate, societal collapse and food as well. As far as I know this has yet to be used for actual modeling, but I think it would be quite informative, as it contains a wide variety and quantified interactions between them. For example, they show how even quite separate societal processes like innovation, migration and consumer demand are all connected via the food system. It also highlights how central our food system is, as the central link between our climate and societal collapse. Societies can withstand many problems, but as soon as the food production stops, things break down fast.

Trade and Famines Today

All these points show that our food system is quite vulnerable to a variety of stressors and we cannot simply store enough food to stabilize it. However, the past also shows that food supply shocks don’t have to lead to famine if there is an outside source that can make up for the loss of food production.

Global catastrophic risks don’t apply uniform stress on our food system. There will always be areas that will be hit less and that might still be able to produce food, even in more extreme circumstances. One paper that explores this is Boyd & Wilson (2022). For all major islands (for example, like Iceland or Australia (which you might count as a continent sized island) they collect empirical data on things like food production, food availability and other factors which are important after global catastrophes. Among major islands, Australia comes out on top for many of those factors. From the perspective of protecting against global famine risk, it is especially relevant that Australia’s food production capabilities are quite large, as it is a major exporter. This implies that Australia could serve as an important stabilizer for global food production, so long as trade remains feasible.

Indeed, the importance of trade comes up in a lot of research that looks into food security, both now and after catastrophes (like the work by Boyd & Wilson). For instance, Wang et al. (2023) use global trade data from 1986 to 2018 to show that the number of countries who trade food and the amount of food they trade has risen considerably over time. This means that food trade is now much more important for the food security of many countries than in the past. Wang and co-authors also raise the alarm that this network could quickly unravel if important food exporting nations introduce food export bans, as this will likely lead to a cascade of food export bans globally, which in turn would make many countries food insecure. Now, and especially after a catastrophe.

All this shows that while our current food system is able to create food security for most of humanity, there are many pathways which could end this relatively stable regime. Wang et al. summarized this as our food system being “robust, but fragile”. We can buffer small shocks easily, if this would also be the case after a major shock is much less certain.

Endnotes

(1) Linking it here directly, because it is so big.

References

Avin, S., Wintle, B. C., Weitzdörfer, J., Ó hÉigeartaigh, S. S., Sutherland, W. J., & Rees, M. J. (2018). Classifying global catastrophic risks. Futures, 102, 20–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2018.02.001

Baum, S. D., Denkenberger, D. C., Pearce, J. M., Robock, A., & Winkler, R. (2015). Resilience to global food supply catastrophes. Environment Systems and Decisions, 35(2), 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10669-015-9549-2

Boyd, M., & Wilson, N. (2022). Island refuges for surviving nuclear winter and other abrupt sunlight‐reducing catastrophes. Risk Analysis, risa.14072. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.14072

Charalampopoulos, I., & Droulia, F. (2021). The Agro-Meteorological Caused Famines as an Evolutionary Factor in the Formation of Civilisation and History: Representative Cases in Europe. Climate, 9(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli9010005

Cottrell, R. S., Nash, K. L., Halpern, B. S., Remenyi, T. A., Corney, S. P., Fleming, A., Fulton, E. A., Hornborg, S., Johne, A., Watson, R. A., & Blanchard, J. L. (2019). Food production shocks across land and sea. Nature Sustainability, 2(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-018-0210-1

Hasell, J., & Roser, M. (2013). Famines. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/famines

Richards, C. E., Lupton, R. C., & Allwood, J. M. (2021). Re-framing the threat of global warming: An empirical causal loop diagram of climate change, food insecurity and societal collapse. Climatic Change, 164(3), 49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-021-02957-w

Wang, X., Ma, L., Yan, S., Chen, X., & Growe, A. (2023). Trade for Food Security: The Stability of Global Agricultural Trade Networks. Foods, 12, 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12020271

Zhang, D. D., Lee, H. F., Wang, C., Li, B., Pei, Q., Zhang, J., & An, Y. (2011). The causality analysis of climate change and large-scale human crisis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(42), 17296–17301. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1104268108