For this post I aim to essentially create a little repository of catastrophic risk lists, so other people can find those more easily and get an overview of how groups of experts with different backgrounds categorize and evaluate risks. The motivation behind both this post and the articles I will be citing, is the idea that to be safe, you have to be prepared and to be prepared you have to know what lurks behind the horizon. Also, I want to show how different groups of researchers go about this and how they focus on sometimes quite different kinds of events. Finally, I want to highlight those catastrophes that most people seem to agree on and how well these risk assessments are taken up by policy makers.

Gotta catch ‘em all

The most extensive of these catastrophe lists which I am aware of is by Tähtinen et al. (2024). They tried to list essentially every possible future threat that societies could face. To bring it all together they looked at 1714 documents and interviewed 54 experts, which left them with 153 potential future crises. They emphasize that this is the most extensive list of things that go wrong on a societal level that there is and I tend to share this assessment. They categorize these crises in 6 distinct categories:

- Political Crises (34 identified): These emerge through societal conflicts, power struggles, and dysfunctional dynamics of existing institutions. The researchers divided political crises into three subcategories:

- Shifts in Governance, Regimes & Power Relations (11 crises): Including phenomena like government overthrow and established surveillance society

- Socio-political Polarisation (8 crises): Covering crises like rising terrorism and disinformation crisis

- Interstate Conflicts (15 crises): Encompassing various forms of warfare and international tensions

- Economic Crises (23 identified): These emerge from market failures and dysfunctionalities in economic systems. They’re categorized into three subcategories:

- Collapsing Economic Institutions (9 crises): Including systemic banking crises and stock market crashes

- Market Frictions & Disparities (9 crises): Covering issues like hyperinflation and mass unemployment

- Adversities in the Public Economy (4 crises): Including fiscal crises and widespread corruption

- Social-Cultural-Health Crises (25 identified): These emerge from socio-political relations, demographic dynamics, and exogenous disruptions. The researchers divided them into three subcategories:

- Demographic Turn (5 crises): Including migrant crises and aging population issues

- Social Erosion (9 crises): Covering phenomena like extreme social stratification

- Blights to Public Health (11 crises): Including pandemics and healthcare service crises

- Technological Crises (31 identified): These escalate in socio-technological systems through technological development and dependency. They fall into three subcategories:

- Socio-Technical Dissonance (10 crises): Including uncontrolled AI and militarization of space

- Technological Hazards (7 crises): Covering incidents like major nuclear plant accidents

- Inaccessibility of Technologies (14 crises): Including energy crises and broadband inaccessibility

- Legal Crises (8 identified): These concern failures in legal systems affecting equality, efficiency, or trustworthiness. They’re divided into two subcategories:

- Inefficient Legal System (5 crises): Including widespread distrust in legal systems

- Discriminative and Oppressive Legal System (3 crises): Covering issues like loss of individual liberty

- Environmental Crises (32 identified): These consist of physical phenomena emerging through natural systems or human disruptions. They’re categorized into two subcategories:

- Natural Hazards & Extremes (23 crises): Including extreme weather events and biodiversity loss

- Human-Made Environmental Emergencies (9 crises): Covering issues like pollution crises and geoengineering failures

Escalating global crises

There are also more directed ways to gather lists of potential crises beyond broad cataloging efforts. The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) report “Hazards with Escalation Potential: Governing the Drivers of Global and Existential Catastrophes” (Stauffer et al., 2023) specifically focuses on identifying hazards that could escalate into global catastrophes or existential threats to humanity.

The report defines hazards with escalation potential as those that, when combined with corresponding vulnerabilities and exposures, could trigger cascades leading to global catastrophic or existential outcomes. Through a comprehensive methodology involving literature review, expert surveys examining 302 hazards from the Hazard Information Profiles (HIPs), and expert consultations, they identified a subset of tenhazards with particular potential for catastrophic escalation. These ten primary hazards are then sorted into four categories:

- Geohazards: Volcanic aerosols that could trigger global cooling and food system collapse

- Biological hazards: Deadly pandemics, antimicrobial resistance, and harmful algal blooms

- Technological hazards: Nuclear weapons and nuclear winter, radiation agents, infrastructure disruption, and hazards related to the Internet of Things

- Social hazards: International armed conflicts and environmental degradation from conflict

Beyond these specific hazards, the report highlighted two crucial cross-cutting risk drivers: climate change (as an amplifier of multiple hazards) and artificial intelligence (as a transformative process with potentially far-reaching implications).

The researchers were able to identify shared characteristics that make these escalating hazards especially dangerous. These include exponential growth and self-propagation, global geographical scope, severe cascading impacts across multiple systems, ability to trigger irreversible systemic shifts, capacity to bypass established response mechanisms, erosion of trust and cooperation, high uncertainty, shared ownership between separate, national governments, technological origins, and development-driven emergence.

The report emphasizes that human choices drive these risks. How societies invest in critical infrastructure, political systems, military capacity, and technological development creates opportunities but also introduces risks. Many of the most dangerous escalation scenarios are directly linked to human decision-making and technological development, highlighting that human agency is a critical factor in both creating and potentially mitigating these catastrophic threats.

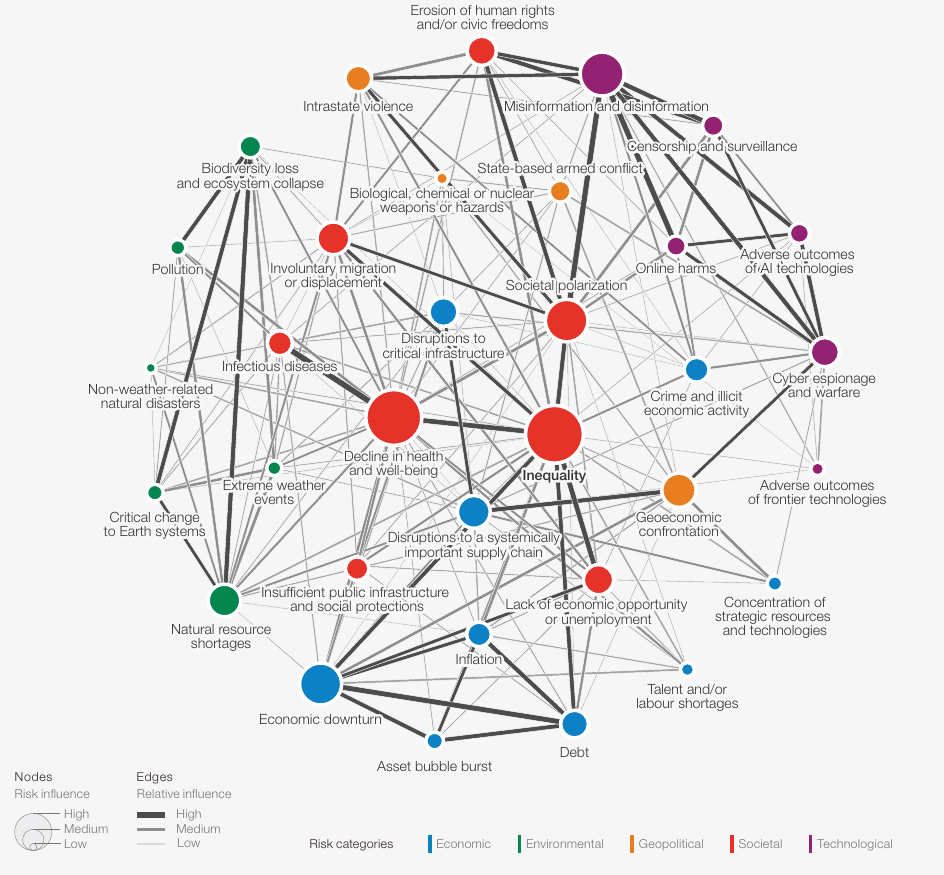

Similar in scope and approach is the Global Risks Report by the World Economic Forum (WEF) (World Economic Forum, 2025). Like the UNDRR report this surveyed actors from academia, government, the private sector and civil society, but an even larger sample (900 experts). The goal in the WEF report was to identify which risks we face in the short term (2 years) and long term (10 years). Generally, the vibes are pessimistic and the majority of survey respondents think that we are in for a rough ride in the short term and an even rougher ride in the long term. This is also a more negative assessment than in the WEF risk reports of the last few years. The survey respondents trace their more negative assessments back to deepening geopolitical and geoeconomic tensions. Especially, in the short term they rank state-based armed conflicts as the number one risk that will cause trouble in 2025. Though this does not mean that they think that armed conflict will be the most severe risk. In the short term the survey respondents think this will be misinformation and in the long term extreme weather events. In addition to ranking the risks, the report also tries to explore how they interact with each other and what kind of risks tend to have a large influence on others (Figure 1). I found this one especially interesting, because it frames inequality as the key issue of our time, as it influences a lot of other potential risks in a very negative way. This is very much in line with inequality also coming up as one of the main culprits for past crises, which we discussed here.

Figure 1: An interconnected map of the global risk landscape

Global catastrophic risk and existential risk

Another community that is fond of making lists of catastrophes is the one focussed on global catastrophic risk (1). Global catastrophic risk involves threats that could cause widespread human mortality or severely reduce well-being worldwide. The research here revolves around how such risks might occur and how they could be prevented or managed. However, it is still debated which catastrophes should count here. But I want to quickly highlight the most extensive summary studies here and what kinds of catastrophes they include.

Ord (2020)

This book is one of the foundational texts of the field of global catastrophic risk. In it, Toby Ord wrestles with the question of what catastrophes are a global risk to humanity and what the chances are that they might lead to human extinction. The main catastrophes he comes up with are: asteroids, volcanoes, stellar explosions, nuclear weapons, climate change, environmental damage, pandemics, AI and global authoritarianism. Overall, he thinks there is a one in six chance that one of these leading to an existential catastrophe this century, with his best bet being AI.

ÓhÉigeartaigh (2025)

Very similar in its aim to Ord, but more recent (and considerably shorter), is this review by Sean ÓhÉigeartaigh. It is specifically about what experts have said in the past about which catastrophes might lead to human extinction and how likely they might be. The list is similar to Ord, but a bit longer. In addition to those already mentioned by Ord, ÓhÉigeartaigh also considers solar luminosity increase (the Sun getting brighter in its life cycle), physics experiments going wrong (e.g. accidentally creating a black hole inside of Earth) and unknown future technologies (e.g. atomically precise manufacturing) (2). Overall, ÓhÉigeartaigh assesses that getting to human extinction is just pretty difficult. For most of the catastrophes, you always have some kind of holdout. For example, if you have a supervolcano cooling the Earth, there are still places like Australia that would be pretty habitable. However, he thinks what might get us all are more the cascading failures of critical systems like power and food supply chains and the resulting chaos and reduced resilience against further catastrophes. Finally, he highlights that the largest danger comes from ourselves. We still have nuclear weapons and might build artificial general intelligence in the future, with very uncertain consequences for all of us. He ends with a sentence that summarizes this succinctly: “Humans may be hard to wipe out, but that will not stop us giving it our best shot.”

Avin et al. (2018)

This study has a bit of a different approach from Ord. Instead of trying to come up with the main existential catastrophes that are out there, they try to think about how we can classify them best. The way they go about this is by thinking about what critical systems are affected (physical, biogeochemical, cellular, anatomical, whole organism, ecological, sociotechnological), how the catastrophe spreads globally (natural global scale, anthropogenic networks, replicators) and on what scale prevention and mitigation failures happen (individual, interpersonal, institutional, beyond institutional). They then try to sort a list of example scenarios into those categories. More specifically they decide to look at asteroid impact, volcanic super-eruption, natural pandemic, ecosystem collapse, nuclear war, bioengineered pathogen, weaponized artificial intelligence, geoengineering termination shock. This is not meant as an exhaustive list, but more to showcase their classification system. While their classification system is interesting in and of itself, it also highlights that there is one system that is especially vulnerable to many of these global catastrophes: the food system (3).

Sepasspour (2023)

There are many further studies who discuss what might count as a global catastrophic risk, but I have highlighted Ord, ÓhÉigeartaigh and Avin et al., because I think they are the best ones. The final one I want to highlight here is Sepasspour (2023). While the general direction of this article is more focused on the importance of an all-hazards approach to global catastrophic risk (4), it starts with a literature review I want to highlight. In this, Sepasspour looked at 31 books and 7 reports to try to find out which are the most often mentioned global catastrophic risks and comes up with the following list: artificial intelligence, biotechnology, climate change, ecological collapse, near-Earth objects, nuclear weapons, pandemics, supervolcanic eruption. Given my own experience in the field, this seems spot on to me and should probably be considered the list of “main” global catastrophic risks.

What future catastrophes might await us?

Besides these catastrophes, about which most already agree that they are big and bad and we should do something about them, there are also potentially less known catastrophes out there, which could become a big problem in the future. Dal Prá et al. (2024) tried to map out such risks in a horizon scan. To do so, they gathered a team of 32 scientists (disclaimer: I was one of them) and asked them first to submit global issues that they thought were flying under the radar. This resulted in 96 potential future risks, which were brought down to those 15 that were deemed as most important by the majority. Here’s a short description:

- Integration of AI in Nuclear Weapons Systems: The increasing integration of AI into nuclear weapons systems introduces new risks by potentially destabilizing the strategic balance, enabling faster decision-making with less human oversight, and creating vulnerabilities to cyberattacks that could lead to accidental launches.

- State Capacity Deficits: Growing government debt, declining trust in institutions, and reduced political stability are hindering governments’ abilities to provide essential services and effectively respond to catastrophic risks, creating a dangerous decrease in state capacity precisely when we need it most.

- Cascading Failures in Global Food Systems: The complexity of our global food system makes it vulnerable to disruptions that can trigger domino effects across food, economic, and health systems, potentially leaving hundreds of millions more people hungry when crop failures, conflicts, or supply chain disruptions occur.

- Climate Change-Induced Displacement: As climate change pushes nearly one-third of humanity outside the historical human climate niche, mass displacement will interact with other crises like conflicts and food insecurity, creating a mutually reinforcing web of challenges that overwhelms societies’ abilities to respond.

- Unclear Future of the Ocean Carbon Sink: The ocean’s crucial role in regulating Earth’s climate by absorbing CO₂ and excess heat may be weakening, potentially accelerating climate change and disrupting marine food webs that billions of people depend on.

- Declining Epistemic Robustness: Our collective ability to make decisions based on accurate information is being eroded by digital media, ideological biases, and the lowering costs of producing disinformation, making it increasingly difficult to coordinate responses to global catastrophic risks.

- Supercharged Surveillance States: Advanced surveillance technologies combining facial recognition, biometrics, and social media monitoring are enabling unprecedented social control, potentially locking societies into surveillance regimes that reduce citizens’ agency and ability to respond to extraordinary crises.

- AI in Bioengineering Arms Races: AI is removing barriers to the development of biological weapons by enabling more people to manipulate biological data for creating proteins and viral vectors, with risks of accidental releases or deliberate use in conflicts.

- Collapse of the Truth in the Age of AI: Generative AI is accelerating our inability to distinguish fact from fiction, creating a societal environment where truth is increasingly devalued and our ability to respond to real threats is severely limited by confusion and mistrust.

- Instability and Collision of Objects in Earth’s Orbit: The proliferation of satellites raises the risk of triggering the Kessler Syndrome—a cascade of collisions generating space debris faster than it decays—which could render low Earth orbit unusable and threaten modern communications, GPS systems, and critical Earth observation capabilities.

- Collapse of Trade Networks Due to Key Hub Destruction: Our just-in-time global supply chains are vulnerable to disruptions at critical trade hubs that could trigger cascading effects, causing export bans, conflicts over resource access, and severe impacts on vital sectors.

- Political Radicalization Driven by Ecological Destabilization: Climate change and environmental threats can push people toward more authoritarian views, creating self-reinforcing cycles where rising authoritarianism makes environmental problems harder to address, further accelerating societal polarization.

- Large-Scale Heat Stress: At just 2-3°C of warming, extreme heat stress will be exceeded during large parts of the year across much of the tropics where half of humanity lives, causing neurological damage, economic collapse, and potentially starting a global socio-economic tipping cascade.

- Accelerated Development of Autonomous Weapons Systems: The rapid proliferation of autonomous weapons systems without adequate oversight is undermining international norms about when nations are at war, blurring conflict boundaries, and increasing the risk of inadvertent escalation.

- Termination Shock from Solar Radiation Management: If solar geoengineering efforts using stratospheric aerosol injection were disabled by disaster or international conflict after implementation, the rapid warming that would follow could be catastrophic, potentially causing multiple degrees of temperature rise in a short period.

This is a pretty wild mix from a very wide range of fields, but I think it gives an interesting overview of what experts concerned with global risks are thinking about. And just like in the review by ÓhÉigeartaigh one thing becomes very clear: all of these risks are of our own doing. The largest future risk for humanity is humanity.

What kind of catastrophes do policy makers consider?

Now we know what kinds of catastrophes experts of global risk see as most important right now and potentially important in the near future. But this is only the first step. It is also important how these risks are considered in policy. Because if none of these insights make it into law or agreements, they are pretty much toothless. Therefore, let’s look a bit at the uptake of these catastrophes by policy makers.

United Nations

One very interesting study in this context of global catastrophic risk and policy uptake is Boyd & Wilson (2020). They examined the UN Digital Library to assess which existential threats receive attention from global policymakers. They conducted a systematic keyword search for terms related to existential risks (like “human survival” and “global catastrophe”) as well as specific risk categories such as nuclear war, artificial intelligence, and synthetic biology. Their analysis revealed that nuclear war dominated the discussion, accounting for 69% of explicit existential risk mentions, while other potentially catastrophic threats like artificial intelligence, synthetic biology, and supervolcanic eruptions received minimal attention or were completely absent from UN documents.

They concluded that there’s a significant imbalance in how international governance bodies address different existential threats, with some major risks being severely neglected despite their potential severity. They argue that this gap should be addressed through three main approaches: creating dedicated UN bodies for each major existential threat (similar to existing ones for nuclear disarmament and near-Earth objects), establishing an overarching body to coordinate across all existential risks, and potentially considering the rights of future generations through the UN Human Rights Council. Their findings suggest that global cooperation on existential risk mitigation needs significant strengthening, especially for emerging technological threats that could develop rapidly in the coming years.

What kind of catastrophes do national risk assessments consider?

I have already discussed national risk assessments in another post, so I won’t go into much detail here, but to quickly recap it: Democratic countries often conduct comprehensive national risk assessments that include global catastrophic threats. A review of assessments from Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and Canada shows varying coverage of major risks. Switzerland has the most thorough approach, addressing artificial intelligence, climate change, near-Earth objects, geomagnetic storms, pandemics, and supervolcanic eruptions. The UK similarly covers most risks except near-Earth objects. Other democracies like the Netherlands, New Zealand, and Canada have more limited coverage, though climate change and pandemics appear consistently across all assessments.

Overall, it seems here that the inclusion of global and/or a bit more unusual risks strongly depends on the country. Some of them do very thorough analysis, while others mostly focus on small, local risks like floods and immediate global risks like climate change or pandemics. It is not really clear to me if there’s a pattern here.

If you have studies that might shine a light on why some countries focus more on global risks than others, please let me know.

Takeaway

When looking at all these different risk complications, it seems to me that global risk experts are most concerned with nuclear threats, artificial intelligence, pandemics and climate change. Also, it becomes pretty clear that generally all risks are either directly caused by humanity or made worse by humanity. While it is obviously bad that we are our own nightmare, it also means that all of these risks are within our own agency. Things caused by humanity can probably also be solved by humanity. A good place to start seems to be to make sure that the risks we face are more consistently included in things like national risk assessments or global policy making, so that we can better explore what might be done about them. Also, inequality pops up in all kinds of assessments as being pretty bad. So, it seems like a good idea to also take care of that.

Endnotes

(1) If you want to know about this field, I wrote a whole systematic review about it.

(2) The famous grey goo.

(3) The implications of this are discussed in another post of this living literature review.

(4) Which essentially means that we should primarily focus on interventions which have a positive effect on all or most global catastrophic risks, instead of getting bogged down in trying to find the best solution for each global catastrophe.

How to cite

Jehn, F. U. (2025, June 18). What could go wrong?. Existential Crunch. https://doi.org/10.59350/k1dc2-9x428

References

- Avin, S., Wintle, B. C., Weitzdörfer, J., Ó hÉigeartaigh, S. S., Sutherland, W. J., & Rees, M. J. (2018). Classifying global catastrophic risks. Futures, 102, 20–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2018.02.001

- Boyd, M., & Wilson, N. (2020). Existential Risks to Humanity Should Concern International Policymakers and More Could Be Done in Considering Them at the International Governance Level. Risk Analysis, 40(11), 2303–2312. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13566

- Dal Prá, G., Chan, C., Burkhanov, T., Arnscheidt, C. W., Cremades, R., Cremer, C. Z., Galaz, V., Gambhir, A., Heikkinen, K., Hinge, M., Hoyer, D., Jehn, F. U., Larcey, P., Kemp, L., Keys, P. W., Kiyaei, E., Lade, S. J., Manheim, D., McKay, D. A., … Sutherland, W. (2024). A Horizon Scan of Global Catastrophic Risks (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 5005075). Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5005075

- ÓhÉigeartaigh, S. (2025). Extinction of the human species: What could cause it and how likely is it to occur? Cambridge Prisms: Extinction, 3, e4. https://doi.org/10.1017/ext.2025.4

- Ord, T. (2020). The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity. Hachette Books, 480 pp.

- Sepasspour, R. (2023). All-Hazards Policy for Global Catastrophic Risk (Technical Report Nos. 23–1; p. 37). Global Catastrophic Risk Institute. https://gcrinstitute.org/papers/068_all-hazards.pdf

- Stauffer, M., Kirsch-Wood, J., Stevance, A.-S., Mani, L., Sundaram, L., Dryhurst, S., & Seifert, K. (2023). Hazards with Escalation Potential Governing the Drivers of Global and Existential Catastrophes. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction.

- Tähtinen, L., Toivonen, S., & Rashidfarokhi, A. (2024). Landscape and domains of possible future threats from a societal point of view. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 32(1), e12529. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12529

- World Economic Forum. (2025). The Global Risks Report 2025.