What would we eat if the sun disappeared tomorrow? Or if our electrical grid collapsed worldwide? This is a topic I am quite interested in, because many of the facets of societal collapse are quite intimately linked to the food system. In previous posts we have explored what happens during a famine, what triggers a famine and how it contributes to societal collapse, how small our global food reserves are, how the collapse of trade influences food availability, where we might be able to produce food in a variety of catastrophes and how a famine can lead to a societal crisis. What we haven’t tackled so far is how we can actually make our food system more resilient in general and what foods we could eat during a global catastrophe. This will be the topic of this post.

What makes a food resilient?

When we ask the question on how to make food resilient, the logical follow-up question is “resilient against what?”. Thankfully, García Martínez et al. (2024) published a literature review where they answer both.

When we talk about resilient foods we have to consider two main scenarios (1):

- Abrupt sunlight reduction scenario (ASRS): This refers to events like volcanic eruptions which emit particles that block out sunlight and thus decrease global surface temperatures and precipitations, decreasing crop yields up to ~90 %.

- Global catastrophic infrastructure loss (GCIL): This means scenarios where the electrical grid is disrupted or destroyed on a global scale, affecting agricultural inputs and thus crops up to ~75 %. This could be caused by things like large geomagnetic storms or an EMP attack.

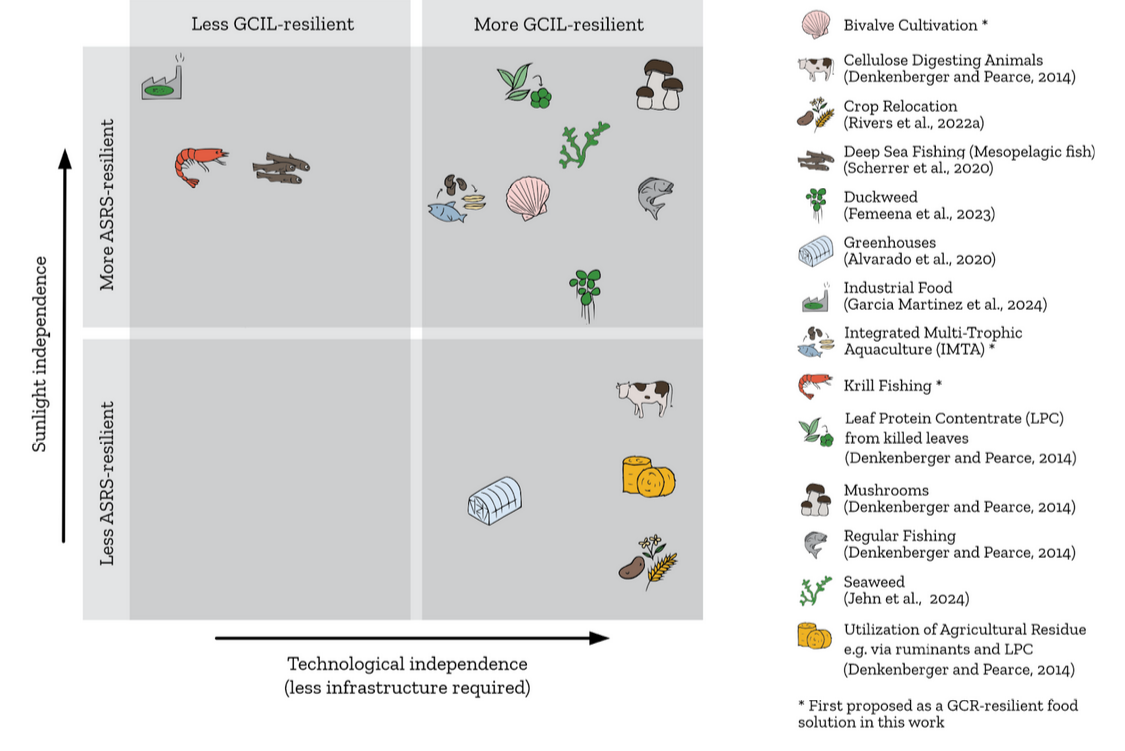

Both of these scenarios can lead to a steep decline in available food. Also, they both likely last for several years. As we have learned in a previous post, our food resources only last for less than a year, this means we have to find alternatives to extend the stocks we have. The two scenarios need different interventions, because they affect different parts of the food system. For ASRS the problem is that the overall amount of energy that flows into the system is decreased, as the sun is delivering massive amounts of free energy every day. Therefore, interventions here need to grapple with the reduced energy input. For GCIL however, you still get the same amount of sunlight and thus energy, but you lose access to other inputs in the food system like fertilizers, pesticides and potentially mechanization if you run out of fuel. Based on these constraints García Martínez and co-authors come up with a variety of possible interventions (Figure 1).

I will not explain all resilient foods here, as the paper already does a good job with this (2), but to highlight some examples of the different categories:

- Suitable for ASRS, but not for GCIL: Foods in this category don’t rely on sunlight, but still require a working infrastructure (think functioning electrical grid or working ports). The best example here are likely so called industrial foods. The idea here is essentially: how can we produce food without relying on agriculture in a classical sense. One of the solutions in this category is single cell protein. This means you have a bioreactor which you fill with some microbial nutrients (e.g. ammonia and minerals), an energy source such as methane (3), and heat it to a cozy temperature. In this bioreactor microorganisms eat the methane and the nutrient and do so quite efficiently. These microorganisms can then be eaten in the form of a flour-like substance (e.g. by adding it to your bread as an additional protein source).

- Suitable for GCIL, but not for ASRS: Here the requirements are the other way around. The food can still rely on sunlight, but not on an intact infrastructure. Therefore, these foods have to be more on the low tech side. A classic example here would be to grow standard crops in Greenhouses. Simple greenhouses can be built cheaply (you need just little more than a transparent sheet and some scaffolding).

- Suitable for both GCIL and ASRS: The foods here must still be possible if you have reduced sunlight, as well as being low-tech. At first glance this sounds kind of impossible. However, there are actually quite a lot of resilient foods in this category. The clearest example here is seaweed. Seaweed does not actually need that much sunlight to grow well and also can be grown in very low tech settings (and has been grown for thousands of years).

Figure 1: Suitability of a variety of resilient foods for different kinds of catastrophes.

Can we actually scale things up?

So, now we know that there are a lot of food sources out there who could feed us even in pretty bleak circumstances. But having the potential to be a resilient food and actually being able to produce enough of that food after a global catastrophe, are two quite different topics. Clear numbers of how quickly we could scale up something like such resilient food production are hard to come by, but I want to highlight a somewhat different topic, which highlights a recent, large scale-up project: Operation Warp Speed (OWS). During OWS the United States was able to scale up the production of vaccines quicker than everybody expected it to be possible. OWS is discussed in detail by D’Souza et al. (2024). Besides explaining how OWS came to pass, their research essentially answers two main questions:

- What kind of properties must a project have so it can be accelerated like OWS?

- Importance: This one’s pretty self-explanatory. If a project is very important, this means a lot of people are interested in it succeeding.

- Time sensitivity: Running something like OWS is quite expensive, therefore the problem at hand should be urgent and costly, like COVID was, so these expenses can be justified.

- Uncommon coordination: Big and important projects often cannot clearly be separated into just entrepreneurial or just governmental. They need both to succeed. To combine them, a kind of unified command structure is needed, which allows us to share risks and reward good ideas.

- Well defined technological goal: Basic research takes time. If your project is still stuck in basic research, it is unlikely that you will be able to bring it to the market in a short period of time.

- Commercial market inadequacy: How much money you can get for something on a commercial market and how valuable something is for society can differ quite a lot. The larger this difference is, the more it is justified to intervene with something like OWS.

- If you have a OWS like project, what do you have to do to accelerate it?

- Lots of money: This is kind of obvious, but if you can throw a lot of money on the problem, there is a higher chance it will be solved. However, what should be noted is that especially in crisis situations, the risk of underspending is much more severe than overspending. If something like OWS costs a few billion dollars more than it was worth, this is not great, but if you think about the counterfactual that you could have gotten a vaccine, but you were too afraid to spend money, this is just a clearly much worse outcome.

- Try a bunch of different stuff in parallel: If you have several potential solutions and one of your limited resources is time, it is quite sensible to try many solutions at once, even if some of them will fail. This costs more money, but when the stakes are that high, it is worth it.

- Try weird and unusual things: Some potential solutions might have a very slim chance of succeeding. However, if they succeed the upside is so large that you should just fund them either way. For example, OWD also funded mRNA vaccines, which were novel, but ultimately turned out to be quite effective.

- Combine push and pull funding: This essentially means that you should give the people money to start working on what you want to see happen (push) and also promise them that they will get more money if they manage to solve the problem (pull).

- Give lots of authority to good leaders: Pushing through with something like OWS is hard and time critical. Therefore, it makes sense to try to find the best talent possible and give them the authority to just push away roadblocks, so the problem is solved quickly and does not get mired down in bureaucracy.

While some of the papers that have introduced resilient foods as a research topic, also include some estimates on how long it would take to scale them up to a meaningful percentage of food production, it is still quite unclear how feasible this is. However, if we ever come into the situation that we actually have to test this feasibility because an ASRS or a GCIL has devastated our food system, using a OWS like approach seems quite sensible. Resilient foods tick pretty much all the boxes:

- Importance: It is obviously important to have enough food to feed your population.

- Time sensitivity: You quickly run out of food, so you have to find a solution fast.

- Uncommon coordination: Many resilient food interventions are novel (at least in scale) and therefore surely need some uncommon coordination.

- Well defined technological goal: Most resilient foods are either already produced commercially or are close to that stage. The question is about how quickly we can ramp up their production.

- Commercial market inadequacy: While theoretically markets should be able to solve a problem with food, it is unlikely whether markets would react sufficiently fast to such a massively sized, unprecedented shock.

Also, resilient foods lend themselves well to parallel approaches like OWS did with vaccines. In case of a global catastrophe, it would make sense to try to scale many of them at once, to make sure that there will be enough food for everyone, even if some of the approaches fail.

Conclusion

Operation Warp Speed demonstrates that rapid scaling of critical technologies is possible with the right combination of resources, leadership, and institutional coordination. While scaling resilient foods would face different (and probably larger) challenges than vaccine development, the core lessons about parallel development, adequate funding, and strong leadership remain relevant. This is especially important given that democratic societies with higher state capacity tend to be more resilient to crises - we need to leverage these institutional strengths to develop robust food alternatives before they’re critically needed.

However, for resilient foods it would also be important if we do more preparation and research now. While many of the resilient foods (like seaweed) are quite established, they are currently not grown in many regions where we would need in case of a global catastrophe, even though they would be feasible there now (e.g. Nigeria) (4). Similarly, some high tech food solutions have yet to be produced on a large scale. And in general, there is little research about how the interactions between the food system and global catastrophic risk would play out, so there is much to be done here.

By taking these steps now, while our food system is still functioning, we give ourselves the best chance of avoiding the cascading failures that have historically turned food system disruptions into societal collapse.

Endnotes

(1) There are other scenarios that could lead to us needing resilient foods, but those are more on the speculative side, so I won’t cover them here.

(2) If you want to dig a bit deeper, here is a blogpost which does just that.

(3) Other energy sources for SCP production include: hydrogen, methanol, acetate, formic acid, paraffin wax, gas oil, peat, plastic, pyrolysis gas, lignocellulosic biomass.

(4) Shoutout to my three subscribers from Nigeria: Let me know if you want to talk about seaweed.

How to cite

Jehn, F. U. (2024, December 19). Resilient foods. Existential Crunch. https://doi.org/10.59350/w8s91-q5a13

References

- D’Souza, A., Hoyt, K., Snyder, C. M., & Stapp, A. (2024). Can Operation Warp Speed Serve as a Model for Accelerating Innovations Beyond COVID Vaccines? (Working Paper No. 32831). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w32831

- García Martínez, J. B., Behr, J., Pearce, J. M., & Denkenberger, D. (2024). Resilient foods for preventing global famine: A review of food supply interventions for global catastrophic food shocks including nuclear winter and infrastructure collapse. EarthArXiv. https://eartharxiv.org/repository/view/7688/