One question that often comes up when discussing global catastrophes and societal collapse is: What is the best place to stay in such a case? This simple question is surprisingly hard to answer, as it depends on a lot of factors. This post is meant to give an overview of the factors that come into play and give some recommendations for the main global catastrophic risks which could lead to societal collapse. It is a bit more on the speculative side, but given the current state of the literature I think those speculations are reasonable and instructive. I mostly focus on the food system, as I think that this will be the most vulnerable process for many people globally in the event of global catastrophe.

What kind of catastrophe are we talking about?

There are a wide variety of global catastrophic risks and we cannot talk about all of them in detail. However, in general you can split them into two major groups:

-

Global catastrophic infrastructure loss: This includes scenarios like High Altitude Electromagnetic Pulses (HEMP), geomagnetic storms, globally coordinated cyberattacks, and extreme pandemics. These events could cripple the global electrical grid, disrupting essential industries (either by destroying infrastructure or harming the workers) and the production of agricultural necessities like fertilizers and pesticides. This would lead to drastically reduced food yields worldwide, severely impacting food trade. An example of a paper that models these effects on agriculture is Moersdorf et al. (2024) (note I am also an author on this paper).

-

Abrupt sunlight reduction scenarios: Such events can potentially be triggered by nuclear war, asteroid or comet impacts, or major volcanic eruptions. Their mechanism is that they could inject particles into the atmosphere, leading to plummeting global temperatures and thus crippling agriculture. Studies suggest potential yield reductions exceeding 90% in the worst-case scenario of a large-scale nuclear war. This is explored in more depth in Xia et al. (2022) where they modeled the effects of a nuclear war on agriculture.

I will focus on these two groups, as the most research on a global scale exists for them. There are a lot of other catastrophes that could plausibly lead to societal collapse, but they often have more complex theories of collapse than the ones mentioned above, which makes it considerably harder to give any meaningful recommendations for places to weather them.

Southern vs. Northern Hemisphere?

In general the Southern Hemisphere seems to be a better place to stay for catastrophes that reduce sunlight. This is mainly due there being more ocean than land in the Southern Hemisphere. One of the main negative effects of abrupt sunlight reduction scenarios is the drop in temperature due to the reduced incoming sunlight. The most recent big modeling study that explores this is by Coupe et al. (2019). They looked at the climatic effects of a nuclear war and simulated this with a modified climate change model. While the world cools as a whole, the cooling effect is bigger in the Northern Hemisphere (1). The Southern Hemisphere temperature is partly buffered by the larger oceans, which keep some of the heat from before the nuclear war. While we do not have similar simulations for large volcanic eruptions (2), there is research that looked at climatic shocks after the eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815 and found that for comparable places the shock in the Northern Hemisphere is often larger (Wilson et al., 2023). Though this also depends on where the particles are emitted into the atmosphere. If you had a major volcanic eruption in the Southern Hemisphere, you would also have more climatic effects there, even though the particles spread globally in a few months. Given paleoclimatic evidence and a lack of nuclear weapon states in the Southern Hemisphere, an abrupt sunlight reduction scenario starting in the Northern Hemisphere seems much more likely.

For global catastrophic infrastructure loss it does not seem to matter if you are in the Northern or Southern Hemisphere. Here the main impact is due loss of fertilizers, pesticides and trade. This hits the economies with the most intense agriculture, which we have examples of in both hemispheres (Moersdorf et al., 2024).

High income vs. low income countries?

As stated above one big factor for global catastrophic infrastructure loss is if a country is high or low income. This is mostly due to the way these countries conduct their agriculture (Moersdorf et al., 2024). High income countries usually use more fertilizers and other agricultural inputs, which makes them more vulnerable to disruptions in the flow of these goods. However, there are also countries like Australia, which are major grain exporters, but do so by using less inputs per hectare than for example Germany. Instead they use more land, but less intensively. This means they would likely be less vulnerable than other high income nations. Combine this with higher state capacity (3) and a high income, and a less import dependent nation like Australia is more likely in a good position to stay stable after global catastrophic infrastructure loss. However, Moersdorf et al. (2024) may imply low income countries have a good chance as well. Their agriculture does not use a lot of inputs like fertilizers right now and so their economy would likely be less disrupted if the flow of these goods ceased.

For abrupt sunlight reduction scenarios high income countries are also likely a better place to stay, as their increased state capacity would likely help them cope better. That said, if sunlight is reduced due to a nuclear war, NATO members and states with nuclear weapons would likely be an exception, as those would be directly impacted by the destruction of the nuclear weapons. Another factor is the latitude of the high income countries. In abrupt sunlight reduction scenarios higher latitudes would be worse for growing crops due to less sunlight and lower temperature (Coupe et al., 2019).

Islands vs. continents?

As noted above the Southern Hemisphere is likely more resilient to abrupt sunlight reduction, as it has more oceans, which buffer the temperature shock. This argument is even more true for islands in the Southern Hemisphere. Based on this line of reasoning Boyd & Wilson (2022) looked at a variety of islands globally and evaluated them on their resilience to abrupt sunlight reduction scenarios. Moreover, many of the assessed parameters focus on the self-sufficiency of islands, which would also be valuable after a global catastrophic infrastructure loss. New Zealand, Australia, and Indonesia are each relatively resilient, though each comes with caveats:

- New Zealand is very dependent on trade, especially when it comes to fuel.

- Australia is overall pretty good, but could be a potential target in a nuclear war, as it is allied with the United States.

- Indonesia is pretty good overall as well, but suffers from low political stability.

In addition, island nations usually have small militaries and are therefore potentially vulnerable against aggressors. One of the biggest trade related problems is the reliance on oil imports. This means that those islands could become increasingly resilient if they switch more to renewable energy, though wind and solar power and biofuels are susceptible to abrupt sunlight reduction scenarios. Nonetheless, they would likely fare much better than continental nations, which would face many of the same problems, as well as having a much steeper temperature decline than the islands.

However, the picture is less clear for global catastrophic infrastructure loss. While the arguments show that some of these islands would be resilient against such a catastrophe, it is unclear if they would be better or worse than countries on continents. As far as I know there has been no research that looks at the question if islands or continents are better for weathering global catastrophic infrastructure loss.

If you know of important studies I’ve missed, please email me and I’ll update this article!

Urban vs. rural?

The main problem when it comes to global catastrophes and cities is that food quickly runs out, as the local food stockpiles are not large enough to sustain the population of cities for long. Baum et al. (2015) did a literature review about the overall resilience of the food system against shortages and came to the conclusion that one of the main problems is that stockpiles run out quickly. Any densely populated areas do not have locally available natural resources that would be needed to grow food in the event of supply disruptions. Therefore, many cities would have much more people than they could realistically feed, which makes rural areas generally a better place to be after global catastrophes.

Food exporter vs. food importer?

Most countries are food importers; exporting is dominated by few major players like the United States for wheat and corn (4). This means that many countries will run into problems with food supplies when trade is hindered by catastrophes, as they lack the capacity (or sometimes the climate and soils) to grow the food that they need. Therefore, it is preferable to be in a country that exports food in normal circumstances, as this makes it more likely it will be able to produce enough food for its population after catastrophes. An example of an exporting nation that also fits the other criteria we have discussed so far is Australia.

So, where should you stay?

To conclude, there is no simple answer on where to stay, as it depends on the catastrophe. However, there are still some general recommendations that I think hold true for many catastrophes:

- Southern Hemisphere > Northern Hemisphere

- High income country > low income country (with the caveat of the high income country not being one that needs a lot of imports to run their agriculture and economy and maybe that it is not a nuclear weapon state or a part of NATO)

- Food exporter > food importer

- Islands > continents (if the islands is not too small and is able to sustain itself)

- Rural > urban

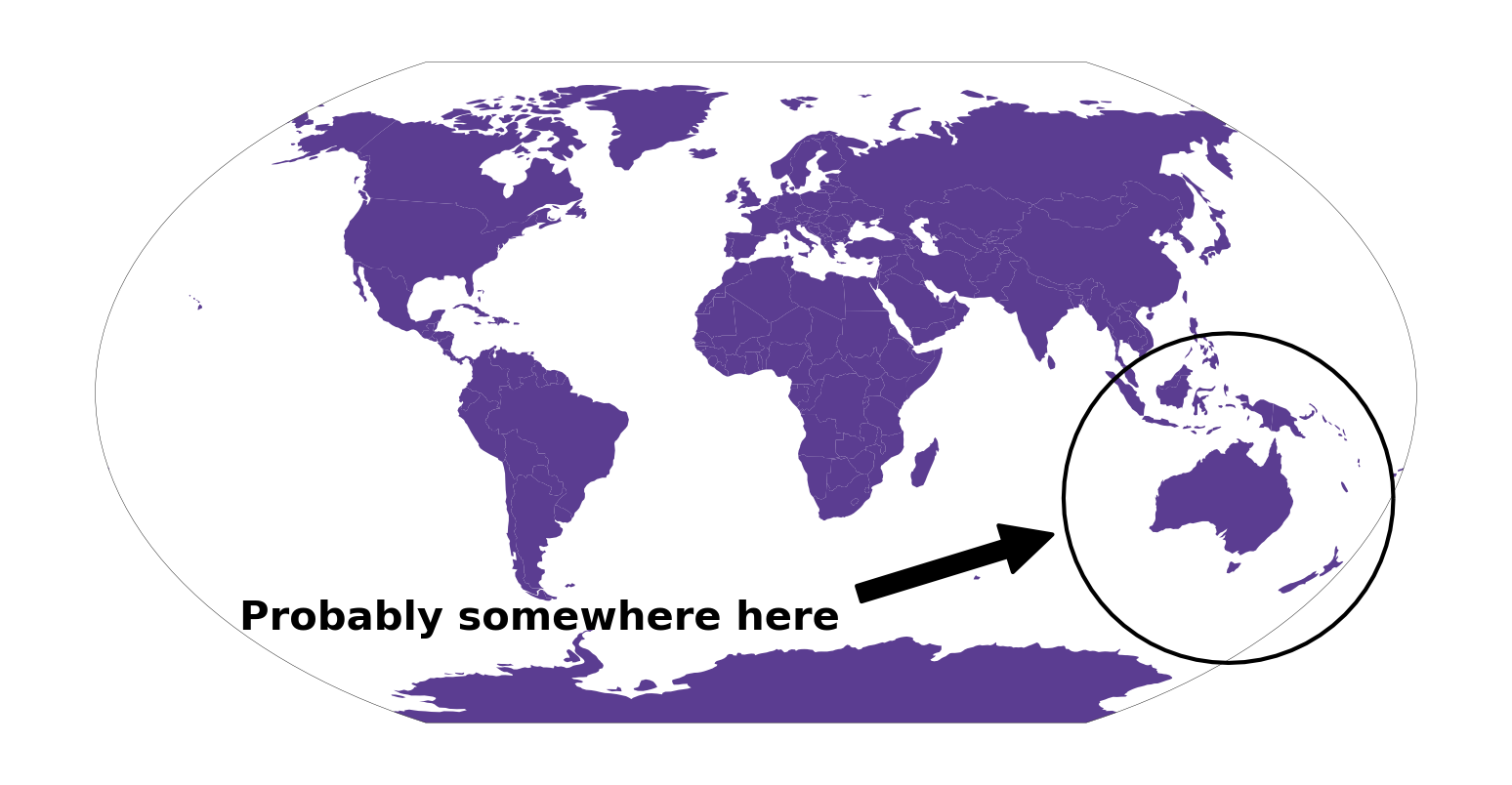

Or to make a visual summary:

Endnotes

(1) The paper does not describe in concrete numbers how much the temperature in the Northern and Southern Hemisphere differ, but they model how many days with a high enough temperature to grow any crops exist on the hemispheres. For the majority of the Northern Hemisphere the growing period is 0 days, while it remains 300 days and more for much of the Southern Hemisphere.

(2) For earlier posts about the effects of volcanoes see here and here.

(3) Which is important for resilience, as discussed in an earlier post.

(4) There are a lot of studies that look into these kinds of distribution, but I found Clapp (2023) especially interesting, as it also explains the history of how we ended up with this focus on so few major exporting nations.

How to cite

Jehn, F. U. (2024, March 4). The best places to weather global catastrophes. Existential Crunch. https://doi.org/10.59350/bgsnc-b5430

References

- Baum, S. D., Denkenberger, D. C., Pearce, J. M., Robock, A., & Winkler, R. (2015). Resilience to global food supply catastrophes. Environment Systems and Decisions, 35(2), 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10669-015-9549-2

- Boyd, M., & Wilson, N. (2022). Island refuges for surviving nuclear winter and other abrupt sunlight‐reducing catastrophes. Risk Analysis, risa.14072. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.14072

- Clapp, J. (2023). Concentration and crises: Exploring the deep roots of vulnerability in the global industrial food system. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 50(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2022.2129013

- Coupe, J., Bardeen, C. G., Robock, A., & Toon, O. B. (2019). Nuclear Winter Responses to Nuclear War Between the United States and Russia in the Whole Atmosphere Community Climate Model Version 4 and the Goddard Institute for Space Studies ModelE. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 124(15), 8522–8543. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JD030509

- Moersdorf, J., Rivers, M., Denkenberger, D., Breuer, L., & Jehn, F. U. (2024). The Fragile State of Industrial Agriculture: Estimating Crop Yield Reductions in a Global Catastrophic Infrastructure Loss Scenario. Global Challenges, 8(1), 2300206. https://doi.org/10.1002/gch2.202300206

- Wilson, N., Valler, V., Cassidy, M., Boyd, M., Mani, L., & Brönnimann, S. (2023). Impact of the Tambora volcanic eruption of 1815 on islands and relevance to future sunlight-blocking catastrophes. Scientific Reports, 13(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30729-2

- Xia, L., Robock, A., Scherrer, K., Harrison, C. S., Bodirsky, B. L., Weindl, I., Jägermeyr, J., Bardeen, C. G., Toon, O. B., & Heneghan, R. (2022). Global food insecurity and famine from reduced crop, marine fishery and livestock production due to climate disruption from nuclear war soot injection. Nature Food, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-022-00573-0