This post primarily centers around a comprehensive 2022 case study conducted by Markus Stoffel and colleagues (Stoffel et al., 2022). This information dense paper is notable for its integration of a literature review and the combination of data from diverse sources and historical records. It underscores the far-reaching societal consequences triggered by a relatively modest maximal global temperature decline of around 1°C.

Background

The “Little Ice Age” denotes an extended period of cold climatic conditions (1), mostly affecting Europe, spanning from the 16th to the 19th century. Our focus will center on the mid-1630s through the late 1640s, which is especially interesting for three key reasons:

- The era from 1621 to 1718 is characterized by the “Maunder Minimum,” signifying a period of low solar activity resulting in reduced global temperatures.

- This time frame witnessed several significant volcanic eruptions: In 1637, Hekla in Iceland erupted with a volcanic explosivity index of 3 (which has a logarithmic scale and a maximum of 8). In 1640 and 1641, Mount Parker in the Philippines and Komaga-take in Japan erupted with a combined volcanic explosivity index of 6. In 1646, Shiveluch in Kamchatka erupted, though the exact size remains uncertain, but likely around twice the impact of Hekla. This unusually high concentration of a number of small to medium sized eruptions added up to a significant amount of climate cooling gases added to the atmosphere.

- In addition, this period was marked by many unusually intense conflicts, notably the Thirty Years’ War (1618 to 1648), along with a large number of civil wars, including the Scottish Revolution, the Catalan Revolt, the War of Restoration in Portugal, the English Civil War, the Irish Rebellion, and the complete downfall of the Ming Dynasty in China. In relation to the population at the time, these were the second most deadly decades since 1400, only to be topped by the Second World War (Roser, 2014).

The paper tries to explain how these conflicts intertwined with the decreased temperatures attributed to the Maunder Minimum and the clustering of volcanic eruptions.

Temperature anomaly in the 17th century

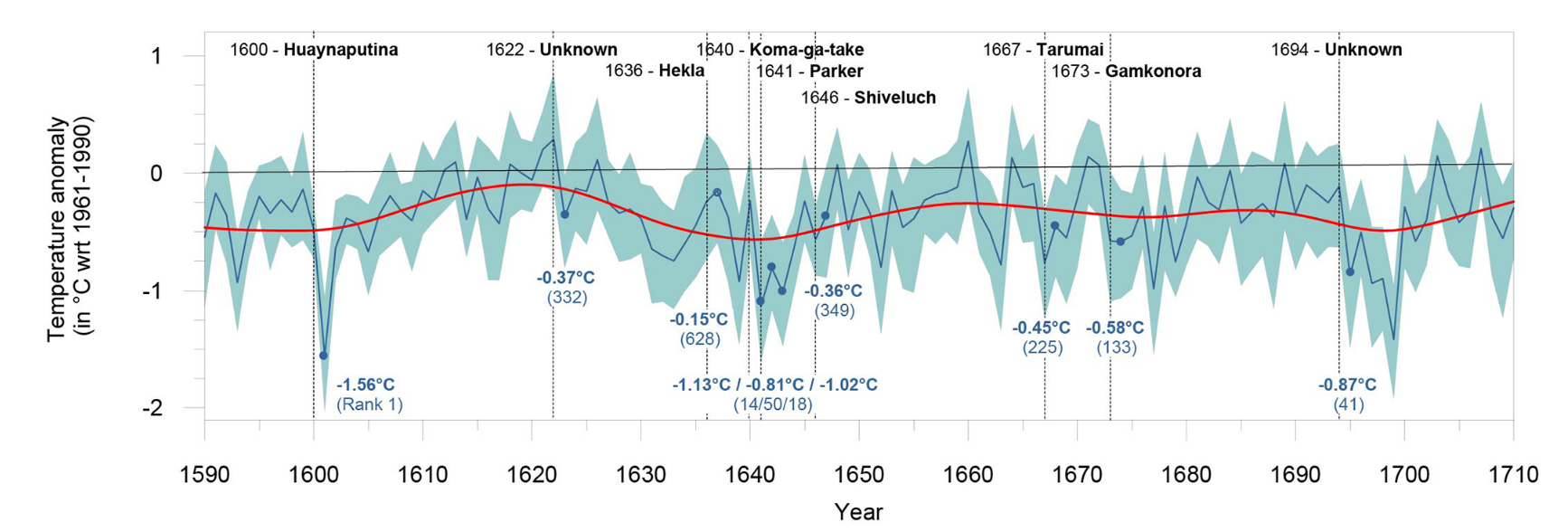

Temperature data from this era can be reconstructed using maximum latewood density records. The density of trees varies in response to the climate conditions when they were growing. Consequently, when we measure tree latewood density, we can use this as a proxy for temperature. Stoffel and colleagues use a publicly accessible dataset of tree rings to reconstruct historical temperatures and make comparisons with present-day conditions (Figure 1). This highlights that the 1630s and 1640s experienced a dip in temperatures. However, it is also similar in size as the earlier dip due to the eruption of the Huaynaputina in Peru (1600). We can also see that during the whole time period the temperatures were lower than with the comparison period of 1961 to 1990.

Figure 1: Tree-ring based summer temperature reconstruction for the Northern Hempisphere. This shows the temperature as a derivation from the temperature we have today. The rank values, shown in parentheses, show the extent of cooling caused by the eruption in comparison to all cooling events documented within the last 1500 years. Red line shows the long-term trend.

Stoffel and colleagues additionally emphasize numerous contemporary accounts that documented lower temperatures, occurrences of “unusual fog,” and skies colored copper-red (2). This underscores the awareness of individuals during that era regarding the unusual phenomena occurring within their natural environment.

Weather and societal distress

Western Europe, particularly the Holy Roman Empire, was grappling with significant challenges prior to 1630, largely due to the protracted Thirty Years’ War. This conflict, fueled by a blend of religious, political, territorial, economic, and social factors, exacerbated by international involvement, had already strained the region. The ongoing warfare had led to food shortages, but the situation deteriorated further when a drop in temperatures commenced. Starting in the early 1640s, there were numerous accounts of cold and wet summers, along with prolonged and exceptionally cold winters. These climatic shifts heightened local conflicts, but by the late 1640s, all parties were so fatigued that continued fighting became difficult, which led to successful peace talks. In some parts of Germany, the population dwindled by up to two-thirds and the total population of the Holy Roman Empire dropped from 16 to 10 million.

Similar reports emerged from Northern Europe and Ireland, as well as more distant locations such as China and Japan. China, in particular, endured severe hardships as it was already grappling with the most extensive drought in recorded history. The volcanic eruptions of 1640/1641 exacerbated the drought, leading to extreme conditions, including cannibalism, widespread epidemics, and ultimately conflict. The year 1645 is notable for having the highest recorded war frequency in China between 850 and 1911.

Can we attribute all of this to the volcanoes?

The data presented by Stoffel et al. unmistakably indicate that the 1630s and 1640s marked a challenging period for large parts of the world. However, it also prompts the question: To what extent can we attribute these difficulties to the volcanic eruptions and their climatic consequences? China was already grappling with an extensive drought, and Europe was entangled in conflicts. Therefore, the role of the volcanoes in these circumstances is not straightforward. The paper offers a clear answer: “it depends.”

The difficulty in attributing volcanism to societal problems in general is also highlighted in another study by Büntgen et al. (2020). Just like Stoffel and co-authors they use big paleoclimatic datasets to draw a direct line from volcanoes to societal effects and just like Stoffel they also conclude with an “it depends”. I mention this here to highlight just how difficult it is to make clear conclusions from paleoclimatic data. The uncertainties are large and it is easy to create a narrative to your liking by cherry picking.

The underlying fact is that the societies examined here were already facing pre existing issues before the volcanic eruptions occurred. While some of these problems were related to climate, particularly in the case of China, most of them were of human origin, arising from conflicts and societal processes that were not well-adapted. This indicates that the societies of that time had vulnerabilities in place, which made them more susceptible to the hazard of volcanic eruptions than they would have been otherwise. In this way, the abrupt climatic disruptions caused by episodes of intense volcanic activity, like the series of eruptions from 1636 to 1646, expose underlying problems. Such crises have the potential to unveil maladapted elements of the underlying cultural, geopolitical, and socioeconomic environments in which they happen.

Lessons learned for today

I found this paper intriguing for several reasons. It demonstrates the extensive effort required to reconstruct historical climates and link them with societal responses. It also illustrates that even a relatively modest temperature drop of 1°C can yield significant impacts when the affected society is vulnerable due to its organizational structure and pre-existing conflicts. This serves as a cautionary tale about how various risks can interact. In this case, Europe had already been weakened by warfare before the temperature drop, and these two factors mutually exacerbated the issues, resulting in a higher death toll than if these events had occurred separately.

Moreover, the paper highlights that it doesn’t necessarily take a supervolcano to have such effects; a series of regular-sized volcanic eruptions occurring simultaneously can also lead to substantial consequences. Lastly, it showcases the self-reinforcing cycle of famines and how it intertwines with crises and warfare, which we discussed in an earlier post.

Finally, I wanted to showcase this paper, because it illuminates the major challenge of creating coherent historical narratives. The researchers conducted a thorough review of existing literature, supplemented by their own data analysis rooted in big datasets of paleoclimatic proxies. Despite these efforts, they were unable to definitively demonstrate the extent to which the observed changes during that period could be ascribed to climate and environmental shifts. Deciphering history is just really hard and we need large amounts of data to be able to come to meaningful conclusions.

Endnotes

(1) Not to be confused with the Late Antique Little Ice Age which we explored in our discussion of how resilience is influenced by democracy.

(2) The fog can be attributed to a dust veil caused by the volcanic eruption, while the red skies are caused by sulfur dioxide scattering the sunlight it gets hit by. This is also the reason for the red sky in “The Scream” painting.

How to cite

Jehn, F. U. (2023, November 22). Societal consequences of the Little Ice Age. Existential Crunch. https://doi.org/10.59350/9bsn4-32g23

References

- Büntgen, U., Arseneault, D., Boucher, É., Churakova (Sidorova), O. V., Gennaretti, F., Crivellaro, A., Hughes, M. K., Kirdyanov, A. V., Klippel, L., Krusic, P. J., Linderholm, H. W., Ljungqvist, F. C., Ludescher, J., McCormick, M., Myglan, V. S., Nicolussi, K., Piermattei, A., Oppenheimer, C., Reinig, F., … Esper, J. (2020). Prominent role of volcanism in Common Era climate variability and human history. Dendrochronologia, 64, 125757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dendro.2020.125757

- Roser, M. (2014). Global deaths in conflict since the year 1400. Our World in Data. https://slides.ourworldindata.org/war-and-violence/#/6

- Stoffel, M., Corona, C., Ludlow, F., Sigl, M., Huhtamaa, H., Garnier, E., Helama, S., Guillet, S., Crampsie, A., Kleemann, K., Camenisch, C., McConnell, J., & Gao, C. (2022). Climatic, weather, and socio-economic conditions corresponding to the mid-17th-century eruption cluster. Climate of the Past, 18(5), 1083–1108. https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-18-1083-2022