To better understand societal collapse we not only must examine the factors that could lead to collapse, but also what might happen during and after collapse. One crucial thing here is economics. What are the direct effects of collapse on an economy? How would prices change? Would trade continue? All important questions, but very difficult to answer due to the complexities of how our economies work. Due to this difficulty only very little research exists for this and those that do exist usually only consider a single aspect or simplified scenarios.

Just a single bomb

One example here is a briefing paper by the UK non-profit Article 36 (Article 36, 2015). They analyze the economic consequences of the explosion of a single nuclear weapon. They argue that the effects of such an explosion, be it intentional or not, will have global consequences, but also note that they can only provide some rough sketches, due to the inherent complexity of the matter.

Their key points are:

- Massive loss of life: Even a single, low yield (100 kT) nuclear weapon could plausibly kill and injure around 300,000 people. The effects would be way worse if we would use the larger bombs we have today.

- Destruction of industries: Often industries are concentrated in a region due better use of economies of scale. Therefore, a single explosion could completely disrupt a key sector of a national economy.

- Destruction of infrastructure: Cities tend to be the main hub of infrastructure, be it education, public transport or administration. If those are disabled, the whole region suffers from it.

- Heavy burden on public finances: It would be extremely costly to rebuild the destroyed city. Also, public health costs in the region would be quite elevated for decades to come.

- Unclear recovery: Due to the high cost and unclear systemic effects, the effects of even a single bomb could make it quite hard for the affected country to recover, even with outside help.

Besides those points the paper repeatedly mentions that these are only vague predictions, as our current economic models have a hard time predicting such unprecedented events. We do have some data from the Second World War where Japan and Germany bounced back quite strongly, even though they endured much stronger damage than a single bomb could do. For example, Hiroshima and Nagasaki both took around 10 years to get back to the population levels they had before the bombs were dropped. However, the biggest bombs we have in use today have one to several megatons of explosive yield, which is several magnitudes larger than the only nuclear weapons that were ever dropped in anger. Therefore, it remains quite uncertain if we could use the reconstruction of Japan and Germany as a comparison class.

Industrial disruption

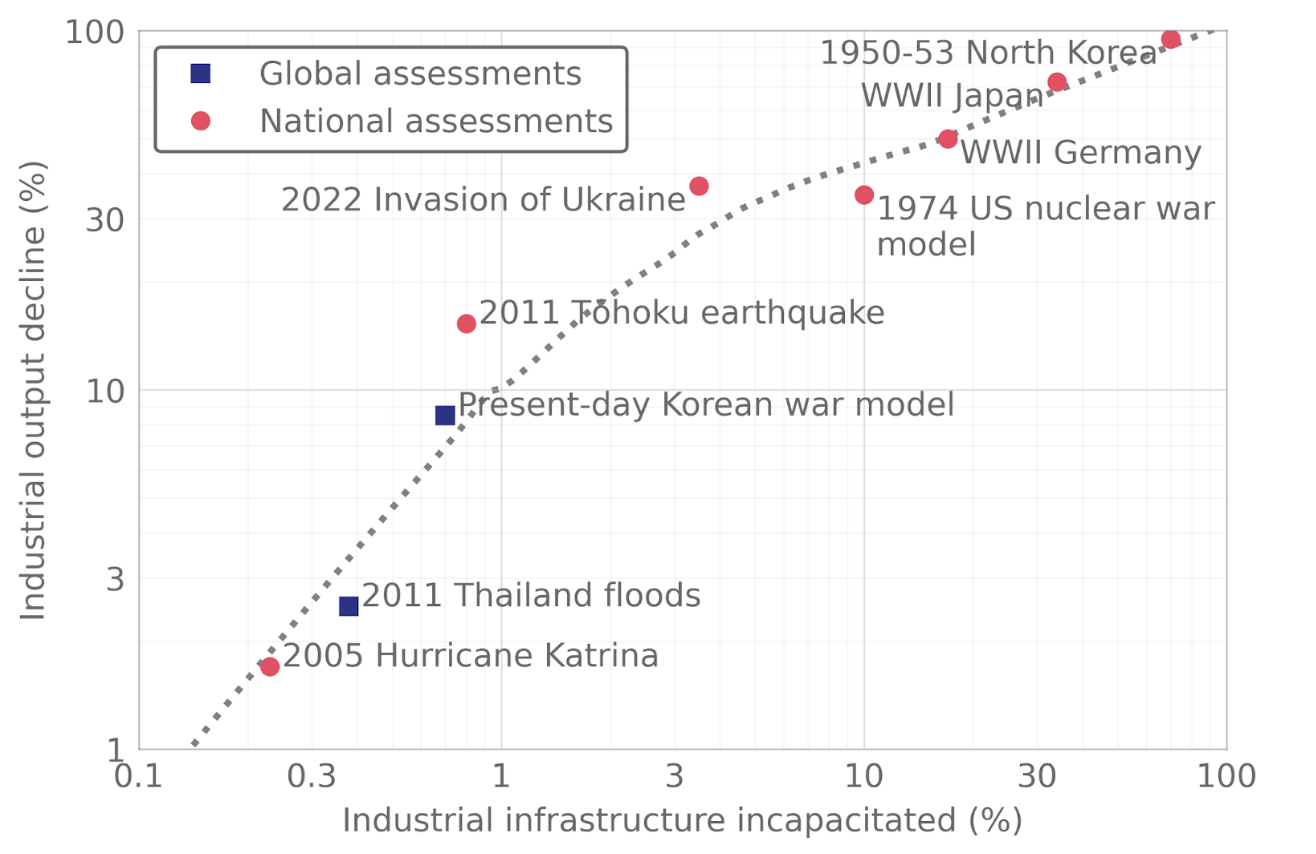

A paper that looks more systematically into the impacts of industrial destruction is by Blouin et al. (2024) (Disclaimer: I am a co-author on this one). The general idea is that, while we cannot easily assess the damages a nuclear war might do to industrial output, we can look into history, to find case studies of how destruction of industry leads to declines in industrial outputs and extrapolate from this. These case studies reach from major hurricanes to the Second World War (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Relationship of incapacitated industrial infrastructure and subsequent decline in industrial output. Based on historical case studies and modelling studies.

In addition to establishing this relationship between industrial destruction and declines in output, the study also assesses how much of industrial capacity would be destroyed in US/Russia and India/Pakistan conflicts. This can be estimated from plausible target lists and the destruction caused by the nuclear weapons detonating above those targets. In the case of the US/Russia conflict the estimate is that this could destroy roughly 3 % of global industrial capacity, which would translate to a 24 % loss in global industrial output from the detonation damage alone. This strongly nonlinear relationship between destroyed capacity and declining output highlights the vulnerability of economies to large scale disruptions.

Modeling agricultural prices after a nuclear war

The studies above relied more on case studies and historical comparisons, but can we still learn something from them by applying economic models to global catastrophes? Due to the difficulties of using economic models so far outside of their training data, very little research on this topic exists. For example, to my knowledge there is just a single study that even attempts to model how a nuclear war (or similar events) might impact the global economy. In this case the study looks at food prices after a nuclear war (Hochman et al., 2022).

If you know of important studies I’ve missed, please email me and I’ll update this article!

The study by Hochman and co-authors uses a general equilibrium model originally developed to understand the economic effects of climate change (later we will discuss why this might be a problem). The model simulates most countries and a total of 15 sectors, of which 9 represent the food system (mainly different crops like rice, wheat etc.), while the rest is for mining, manufacturing, construction and transport. They force the model by providing the changes in agricultural productivity due to worsened climate after a nuclear war. Their scenario is a smaller exchange between India and Pakistan, resulting in roughly 2-4°C decrease of the global mean temperature.

The model makes one quite big assumption: it does not consider the destruction caused by the bombs. It basically models a world where everything is as today, with the one exception that agriculture is suddenly much less productive. This means it also does not consider big knock on effects. India is a large food exporter and having it effectively removed from the market by the destruction from a nuclear war would send additional shockwaves rippling through the global economy. In addition, it is the most populous country in the world and many of the people living there would likely want to migrate from India in such a scenario.

But even this incomplete picture of the situation already shows that this would massively impact our food system. They find that global calories would likely decrease by 10-12 % and also see short time price peaks. However, their model also finds that prices for staple foods quickly go down again, as farmers switch away from livestock and vegetables to produce more staple crops. All this comes with one additional caveat: the results are only valid under the assumption that global trade continues as is, which might not be the case, after such a massive shock.

Do we even have the right tools to model global catastrophes?

The papers we have discussed hint that any global catastrophe would likely be very bad for our overall economic outlook. But it also shows that we do have large difficulties in even applying our current tools to such tasks. Modeling the economics after nuclear war was only possible by excluding the direct impacts of the war and modeling trade is done on such an abstract level that it is often difficult to draw direct lines to the way trade is actually occurring. This leads to the question: Do we even have the right tools to model and analyze our economy after global catastrophe?

One global risk where this question is discussed more thoroughly is climate change. A well known paper here is by Weitzman (2009). The main argument is that the way cost-benefit analysis is done for climate change is fundamentally flawed, as it does not properly account for the uncertainty around catastrophic outcomes. The core problem is structural uncertainty: we don’t just face unknown outcomes, we don’t even know the true probability distribution of those outcomes. We have to estimate it from limited data. When you account for this estimation uncertainty mathematically, you get a distribution with fatter tails than climate economic models typically assume. Extreme events become more probable than thin-tailed distributions would suggest.

Weitzman builds a toy model which showcases why this matters. In his model, the probability of catastrophe declines polynomially as the catastrophe gets worse, but the disutility (how much the catastrophe hurts) grows exponentially (the more you lose, the more each additional loss hurts). Exponential growth beats polynomial decline. This means that even very low-probability catastrophic outcomes can dominate the entire expected damage calculation. The problem is that climate economic models usually use thin-tailed distributions and arbitrary cutoffs for extreme damages. This means they are effectively assuming we can ignore catastrophic outcomes because their probability is negligible. But if the tails are actually fat, this assumption breaks down. If a model ignores the fat tails of the distribution, it has to make much more positive predictions by default, as it ignores the worst parts.

Weitzman’s critique applies to every model that does not consider tail risks properly, no matter the underlying structure. But in complex, global questions like trade policy analysis, climate economics, and large-scale policy simulation one kind of model is used especially often: general equilibrium models. These kinds of models try to simulate an entire economy and how prices react to changes (e.g. production shocks). Their problems have been summarized in a review by Stiglitz (2018). Generally, one of the things you want from a model is to predict catastrophic changes, because those are the ones that hurt most. If GDP growth is 2.8 % or 2.9 % does not matter that much, but if you have a market crash, that hurts. The problem is that general equilibrium models fail at exactly that. They have quite a hard time predicting sudden downturns.

This often gets attempted to be fixed by introducing additional parameters. However, additional parameters always make it easier to just produce a nice looking overfit. The problem with these kinds of models is that they work on quite a high level of abstraction. It doesn’t actually model how households, companies or countries behave or react. It just calculates an equilibrium price. And thus it cannot really tell you anything about changing expectations or values. The models solve this by simply assuming that humans are completely rational actors. But they are not and their behavior is what we actually want to predict, not the future state of some idealized price. This means these models assume the thing we are most interested in as static. As they fail this, they also fail to predict catastrophic outcomes, as these are based on changing expectations, behavior and values. The simple structure of the models also does not account for amplification of shocks in the system. It assumes that shocks can only ever come from the outside. However, from systemic risk research we know that amplification of risks in a system and a risk arising from the system itself regularly happen.

When we think about global catastrophes, another problem creeps in. Population is usually assumed to be an external factor, meaning that the model just assumes a stable population a priori. However, after global catastrophes the loss of life is likely one of the most important factors for economic consequences (2).

Finally, the economic models only look at a single catastrophe at a time. What would happen if we have massive damages from high warming plus a pandemic (3)? We simply do not know.

Are we going to be able to model economics after a global catastrophe anytime soon?

Can you calculate a price after a catastrophe? Maybe, but it will always be a guess, as most of the available tools that just are not made for the task. Economic models are ill equipped to model the effects of global catastrophes, but even the first attempts made highlight the potential for massive consequences. To improve predictions here economic models have to focus on outcomes outside of GDP, like lives lost and we also have to work on improving the missing feedbacks. Empirical work could improve, but this likely only works for climate change, as there simply do not exist any reliable training data sets for catastrophes like nuclear war. Overall, it seems that it will be quite some time until we can make any usable predictions here and in the meantime we should be quite careful of any economic prediction that involves global catastrophes. This all harks back to modeling of a whole economy being really difficult. We cannot even accurately forecast recessions today, but at least we have data to calibrate the models on. Simulating global catastrophes thankfully cannot rely on empirical data, but this makes it much more difficult as well.

Endnotes

(1) Agricultural optimization aligns with local climates. Short-term climate shifts therefore incur higher costs than long-term ones. As climate shifts, initial productivity decline is substantial, but over time, agriculture adapts and starts to resemble places with similar climates before the shift happened. Comparing productivity across current climate zones may forecast long-term outcomes, yet may underestimate short-term damages, given the time required for agricultural adjustment.

(2) In an earlier post we have discussed how a shrinking population is one of the parameters that can bring a society back into equilibrium with the carrying capacity of its surroundings. However, this equilibrium can be on a much lower population and technological level.

(3) This example is actually something that seems to be getting more likely over time. Increased human population and animals migrating to cope with higher warming produce much more opportunities for disease to be transmitted from animals to humans.

How to cite

Jehn, F. U. (2026, January 14). End time economics. Existential Crunch. https://doi.org/10.59350/10f7p-hc578

References

- Article 36. (2015). Economic impacts of a nuclear weapon detonation.

- Blouin, S., Jehn, F. U., & Denkenberger, D. (2024). Global industrial disruption following nuclear war. EarthArXiv. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.31223/X58H9G

- Hochman, G., Zhang, H., Xia, L., Robock, A., Saketh, A., Mensbrugghe, D. Y. van der, & Jägermeyr, J. (2022). Economic incentives modify agricultural impacts of nuclear war. Environmental Research Letters, 17(5), 054003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac61c7

- Stiglitz, J. E. (2018). Where modern macroeconomics went wrong. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 34(1–2), 70–106. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grx057

- Weitzman, M. L. (2009). On Modeling and Interpreting the Economics of Catastrophic Climate Change. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 91(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.91.1.1