Existential risk is not something static which lives outside of humanity. It is something humans shape. This can be directly, such as things that are created or deployed by humans like nuclear weapons. Or it can be indirectly, like whether or not humans have sufficiently prepared our infrastructure for major volcanic eruptions. This means that human actors can and do increase the hazards we face or worsen our vulnerability to existing hazards. But not everybody has the same influence on this. My neighbours do not have any influence on the question if there will be a nuclear war between Pakistan and India. The power and resources to influence such events is usually concentrated in very few groups (1). But who might want to destroy the world? Who might have the capacity to destroy the world, but no motivation to do it? How are we vulnerable to these risks? And what happens if catastrophic capabilities and motivations of an actor align?

Individual bad actors and the “Doomsday Button”

Two major early works on agential x-risk were Torres (2018a) and Torres (2018b). They try to catalogue all the kinds of agents (individuals or groups) that could have the potential to destroy the world, either on purpose or by accident. They highlight that there should be increasing global concern about those who express omnicidal beliefs, especially when faced with increasing accessibility of dual-use emerging technologies, meaning technologies with potentially high destructive potential like AI or biotech. Also you never know what future scientific breakthroughs have in store, there is always the chance that one day a technology might pop up which is super easily accessible and super destructive (2). The only chance we might have in such a case is to try to understand the actors who might want to use such weapons.

If they had the chance, who would willingly commit “omnicide” - literally, the act of killing everyone? Torres (2018a) develops a framework to assess these kinds of actors. The idea here is that the methods by which bad actors try to destroy the world is less important than their motivation. If their motivation is understood, there is a higher chance to stop them. The first insight here is that this means that we can exclude most conventional terrorists. For example, rebels fighting against an authoritarian regime in their home country do not have an incentive to use weapons of total destruction. If your goal is to free the people in your lands, it does not really make sense to kill them. This is a bit abstract, but Torres (2018a) suggests a simple thought-experiment to determine who we should consider apocalyptic agents: Imagine there is a button you could press, which would instantly kill all humans. According to the paper, every person who would push this button is an apocalyptic agent.

This means we are left with people who think that the current state of Earth (or even the universe) is so irredeemably bad that the only reasonable thing to do is to kill everybody. While this is certainly a very extreme position, we know from history that such people have existed. Torres outlines six examples of ideologies whose adherents might press the “Doomsday Button”. While Torres (2018a) gives the framework, Torres (2018b) provides the examples to fill the framework, so let’s combine the two here:

Apocalyptic terrorists

These are people who believe in some kind of coming apocalypse, would like to see it sooner and contribute to this end if they can.

An example cited here is James Ellison. He was the leader of “The Covenant, the Sword, and the Arm of the Lord”, a far right, anti-government militia in the United States. While they started as a “normal” Christian fundamentalist cult, Ellison formed them into an active terrorist group. He had the idea the Second Coming of Christ would only happen after an apocalyptic race war between white Europeans and everybody else. This means that if he would be able to start a world destroying race war, Christ would return sooner. Ultimately, the group was not really successful in attaining their goals, but one could easily imagine them pushing the “end of the world” button (3).

Misguided moral actors

“Misguided” in the context of the Torres papers refers to actors who do not subscribe to the long-term transhumanist consequences of classical utilitarianism. This means especially believers in negative utilitarianism, who subscribe to the idea that only the prevention of negative experience matters. Therefore, any world which includes suffering should be avoided. As all worlds contain suffering, none should exist. Or said more simply, dead people cannot feel pain.

Fortunately, this quite extreme view is only held by some philosophers tightly locked away in academia. However, nihilism cults like ‘efilism’, the anti-natalist ideology behind the 2025 bombing of a Palm Springs fertility clinic, have surfaced more in recent years, but they at least seem to be sticking with conventional weapons for the moment.

Radical ecoterrorists

These are people who think that Earth (or Gaia) would be better off without humans. We had our chance to live in peace with this planet, we spoiled it, so we should just be extinct and let this planet find its way back to equilibrium again.

Examples of such ideas in the wild are the fringes of the deep ecology movement. One of the more well known groups affiliated with these ideas is the Gaia Liberation Front. They state that their mission is to extinguish all humans, as we cannot be trusted with Earth. To bring this about they think that a pandemic that can only target humans would be most well suited, because other methods are too impractical (like mass suicide) or too destructive (like nuclear war).

Idiosyncratic actors

This category includes ‘lone wolves’ or fringe cells. They can be part of loose communities online or evolve organically alone, and often pull from a personal or eclectic range of ideologies. We can find many such examples in the US school shootings epidemic, and a particularly famous one is Eric Harris, who was the shooter at the 1999 Columbine High School massacre. In his diaries he explained that he wanted to see the world burn and kill mankind. Fortunately Eric Harris did not have the means to see the world burn, and the ‘lone actor’ concept has received a lot of counter-terrorism attention over the last few decades when it comes to dangerous weapons.

Non-human actors

Besides these actors where we can give historical examples, Torres also argues that there are two further, more hypothetical groups: value-misaligned machine superintelligence and belligerent extraterrestrials. But for obvious reasons we can only speculate about the ideas and incentives for such actors.

What might bring people to press the Doomsday Button?

Besides Torres, there are other people who have looked into such feelings in the general population. In other words, what might cause ordinary people to feel motivated to press a doomsday button if one existed? There will always be insane people, malignant narcissists and frothing zealots to account for, but wider systemic problems can raise the net level of extreme beliefs in the general population who otherwise wouldn’t hold them, which might increase levels of terrorism without proper social support.

Based on data from British elections, how people change their beliefs when they feel threatened is explored by Stevens & Banducci (2022). They show that growth spikes in extremism might be correlated with feelings of threat, both in normative and personal spheres. Personal threats include things like feelings of existential insecurity. Normative threats can include climate change (mentioned by Torres in the papers described above), feelings of cultural erosion, or increasing authoritarianism. Apocalypticism and doomsday sentiments have historically seen greater proliferation during times of crisis, such as the Cold War. Feelings of existential insecurity might mean that a greater-than-average number of people feel increasingly drawn to beliefs that the world is better off destroyed or fundamentally altered than it is continuing along its current trajectory. However, issues arise if we rely too heavily on the idea of “citizen terror”, which we shall explore now.

Problems with the “individual actors” framing

So far we have explored in great detail what has and what might motivate individual actors or small groups to believe in - or even to try to cause - omnicide. However, this does not mean that this is the most likely way that omnicide or global catastrophe might be caused by humans.

There is a recurring theme in existential risk literature (for example the work by Torres explained above) that strongly emphasizes the risk of terrorists or single actors causing a global catastrophic event. However, this argument lacks somewhat, as there might be actors who theoretically might want to destroy the world, but they clearly lack the resources to do so and it seems plausible that they won’t get them anytime soon. In addition, in the last decades the world has seen massive investments into international CBRN counter-terrorism work, further decreasing the chance that a splinter group will have the chance to end the world. Finally, the question is: would most of the people holding the beliefs outlined above actually be able to extinguish all of humanity?

In general, it seems pretty hard to find people who would want to destroy the world for real and also have the capability to do so. Kallenborn & Ackerman (2023) thoroughly went through the literature in an attempt to find such groups, but weren’t able to find any that tick all the boxes. Groups usually have the motivation to destroy the world, but not the capabilities for a direct attack. Though they think it is plausible that such groups might exist in the future, focusing on building resilience and addressing societal vulnerabilities is the best way to lower the risk. They also highlight that while there currently is no terrorist group which could destroy the world, there have been groups that had the will and capability to spoil risk mitigation measures, but got their timing wrong. This means, currently there is no ongoing risk mitigation measure for global risk, but for example, if there would be an asteroid on the way to Earth, terrorists would likely be able to sabotage a mission to deflect it from hitting Earth.

The problem of making apocalyptic terrorism the center of agential risk focus is explored in Meggitt (2020). The category of “apocalyptic terrorism” is deceptive and should not be attributed lightly as it leads to false positives. Terrorism analysts have shown that ‘apocalypticism’ is often flexible and debated within terrorist groups like ISIS, used as a strategy to gain bargaining power, or to boost recruitment or membership retention in hard times; its emphasis waxing and waning relative to the group’s fortunes.

An interesting case study is presented by Juergensmeyer (2003). He explored the motivations of members of Aum Shinrikyo, a group often used in x-risk discussions as an example of genuine omnicidal intent and follow-through. After conducting interviews with multiple cult members after the Sarin gas attack, both free and in jail, Juergensmeyer concluded that despite their apocalyptic rhetoric, their goal was not to annihilate humanity or cause a GCR. Instead they believed that their organisation would help them survive an apocalypse caused by external nuclear forces. Their actual motivation was being a part of those survivors that would rebuild the world after the apocalypse and that they would hold power in Japan. Their apocalyptic framing served them for meaning making, but was not their actual goal. There is no great evidence that they really wanted to cause human extinction.

Since many of Torres’ papers were written, the field of existential risk has benefited from the inclusion of researchers with counter-terrorism, biosecurity, politics and CBRN expertise, as well as simply having had more time to consider the multiple hazard and high vulnerability areas of this risk. While recognising the importance of monitoring dangerous ideologies in numerous but incapable actors, existential terrorism has moved away from this narrow focus and is starting to focus more on systemic vulnerability risk factors and their exploitation by malicious actors. Kallenborn and Ackerman (2023) advocate for resilience-strengthening solutions as well as monitoring on the agents side. Meanwhile, examinations have also grown to include other agents, capabilities and systemic vulnerabilities too.

Institutional bad actors

It seems far-fetched that an isolated individual could destroy the world today, even if they had ideological motivations to do so. However, institutions which endanger the world already exist. Not only should we ask “who might press the doomsday button?”, but also “who might build it, and should they?”.

Institutions are made up of networks and groups of people, have access to greater resources and legal protection to build capabilities, and often use systemic vulnerabilities to their advantage. Understanding these institutions, their capabilities and the wider societal vulnerabilities at play is integral to building a fuller and more accurate picture of agential x-risk.

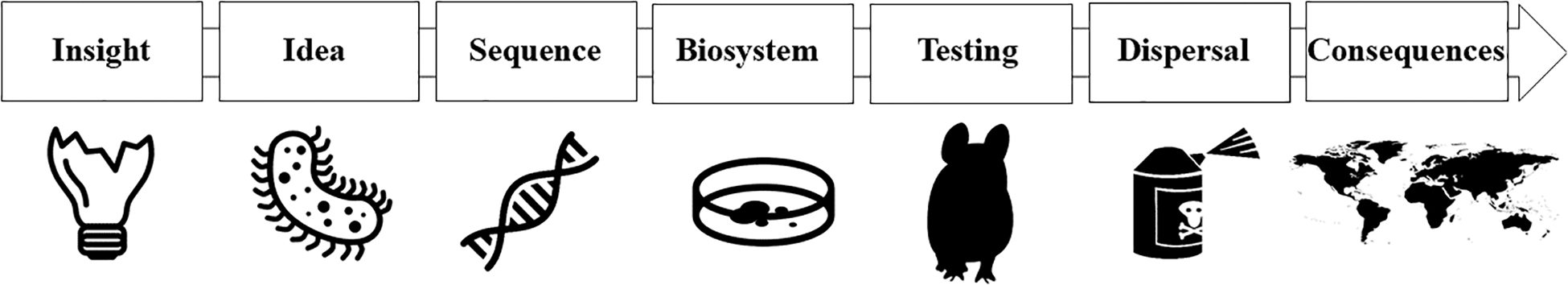

A comparison of threats from malicious actors at different scales is done by Sandberg & Nelson (2020). They developed a simple model for this in biorisk (Figure 1). The idea is that if you want to be a successful bioterrorist, there are many steps you have to do right. This starts from having the insights of how you want to kill everyone, implementing and testing the idea, evading capture, and scaling the enterprise to global proportions. Each of these steps has a specific set of difficulties, each of which has to be overcome in order for an actor to progress to the next step. Overcoming these difficulties often requires having resources and progress is harder the fewer resources you have. Due to these constraints, their model comes to the conclusion that, even though less powerful malicious actors are more numerous, it is more likely that less numerous but more powerful actors would be able to overcome more difficulties and therefore progress through the entire risk chain. Though Sandberg and Nelson also acknowledge that this might change in the future (if these steps get considerably easier as technology progresses), the results of their model indicate that most current risk from malicious actors is enabled by their place inside resource-centralising institutions.

Figure 1: The model of which steps you have to master to be able to cause global biorisk.

This scary possibility is one that CBRN, de-radicalization and biosecurity experts have devoted huge amounts of time and resources to minimizing: a high-powered actor becoming sufficiently motivated to deploy the catastrophic capabilities they are already in possession of, and no-one around them being educated to notice or report it until it is too late.

But what happens when institutions’ very incentives are to build these capabilities and keep them secret? A highly destructive, highly accessible weapon which might be discovered in the future is, most likely, not going to come from a DIY amateur biolab, or a single genius researcher. It is much more likely to come from a group of people working in an AI development lab, biosecurity facility, or defence-tech company. Their investors, another group of people with highly centralised resources, may have a strong incentive to market, use or sell this new invention. Because of this level of resource and power centralisation, it’s no exaggeration to say that, in today’s world, the agential threat posed by terrorist groups is dwarfed by that posed by Peter Thiel or Sam Altman, enabled by the institutions that they operate within and the systems vulnerabilities those institutions exploit.

Specifically focussed on the institutional actors is a short overview article by Kemp (2021) (4). In it Kemp argues that existential risk is mainly driven by big, institutional actors, as everybody else has too few resources to meaningfully move the needle. The pathways that have been identified so far to end the world are things like artificial general intelligence, catastrophic biological threats, climate change, lethal autonomous weapons systems and nuclear weapons. You cannot build nuclear weapons in your backyard, neither can the lifestyle of an individual meaningfully influence how many ppm carbon dioxide are in the atmosphere.

To do these things you have to have lots of power and lots of resources, and lots of time to work on them without being stopped.They are something only very large actors like the military-industrial complexes of several countries, the fossil fuel industry, or Big Tech can enable or accomplish. In many (or maybe all?) of these institutions we can see that their profits are privatized, while the potential downsides are public.

Let’s look at some examples:

- Artificial general intelligence: There are very few AI companies who actually build powerful new models, and the resources needed to build such models are highly concentrated in a few groups of people. Presently the biggest ones are OpenAI, xAI, Anthropic and Deepseek. It is unclear if their models even could lead to general AI, but what is clear is that it is extremely resource-intensive and therefore difficult to work on them, because they need large amounts of electricity and compute to be built and run.

- Climate change: Globally around 100 producers are responsible for the vast amount of carbon dioxide emissions. Similarly, more than half of the global cumulative emissions fall to just three main actors: the US, EU-27 and China. Finally, only six countries hold 80 % of the global fossil fuel reserves.

- Nuclear weapons: Almost 90 % of all nuclear weapons are held by two countries: the United States and Russia. And for the remaining 10 % you just have to add 7 other countries. The maintenance and production of American weapons is bundled up into just 28 companies. The command chain to use those weapons are quite short. In the United States the president has sole authority to order a nuclear strike. There are four key advisors, but their consent is not required.

All this means that most human-made catastrophic hazards are highly concentrated in small networks of powerful actors. The United States military could easily be considered as the largest contributor to global risk. They emit gigantic amounts of carbon dioxide, they control the most advanced nuclear arsenal, are at the forefront of developing autonomous weapons and surveillance technologies and have by far the largest military in the world.

What makes such actors so tricky to reign in is that they often use their power and resources to distribute misinformation, so public opinion is swayed and they can continue their mission. Clear examples here would be NATO trying to discredit nuclear winter research (5) or the fossil fuel industry financing large misinformation campaigns for decades. Similarly, these powerful organizations often lack efficient oversight, which allows them to keep risks secret. Like the fossil fuel industry knowing about the fact of global warming for decades.

In the future, some of those pathways to global catastrophes might get into the reach of individual actors, but for now it seems pretty obvious who creates global risk and we should focus our efforts on those actors. The motivation of these actors is likely not to ruin the world, but we cannot get around the fact that they do endanger us all. They are driven to accept these risks because they have a profit motive and face competitive dynamics.

There are also attempts to combine these two strands of ideas focussed on individual and institutional actors. A report by Althaus & Baumann (2020) argues that we should also look at malevolent individuals in positions of power. They argue that some of the worst things ever done to humans were caused by dictators, who had large institutional power behind them. Clear examples of this would be Hitler or Stalin. These individuals likely did those horrible things because they had power, but also because they scored high in Machiavellianism, narcissism, psychopathy and sadism. These are often properties that individuals often have who are power and status seeking and also harbour extreme beliefs. Therefore, existential risk mitigation should also be done via exploring these traits, how they can be detected and how people with these traits can be excluded from ever gaining power. Something like a similar screening process is already done in counter-terrorism, for example in high security biolabs. If more scrutiny can be directed towards actors already operating within powerful institutions, agential x-risk might be significantly lowered via this type of intervention.

Policy around global risk

The concentration of global catastrophic risk in the hands of relatively few powerful institutions raises a critical question: how do those responsible for governing these risks actually perceive this challenge? Understanding how policymakers navigate this landscape of concentrated power is essential, as they represent one of the few potential checks on these institutional actors. However, policymakers themselves face significant constraints. Research by Nathan & Hyams (2022) provides direct insight into how those closest to global catastrophic risk governance perceive their own capacity to address these challenges, revealing both the opportunities and structural barriers that shape policy responses to our most dangerous institutional actors. They interviewed 16 civil servants, civil society group representatives and individuals from the private sector in the UK, US or Europe and tried to distill these interviews. This brought up four themes on how these people think about global risk:

- Scepticism: They realize that current solutions are often lacking and that the government is too often just in a reactive role. New systems are needed to plan before disaster happens. This skepticism directly reflects the challenge of regulating the powerful institutional actors identified earlier. As one UN policy lead put it regarding pandemics: “if a crisis hits tomorrow, it’s too late.”

- Realism: Global catastrophic risks are just a very complex problem, which often requires long times to implement solutions. This is just really hard in a policy world which is focussed on the short term. As one health security expert noted, there’s “realpolitik because you can have as many agreements as you want, but if you’ve got the UK and the United States producing something, politically, their first obligation is clearly their own citizens.” This reflects the challenge of governing institutional actors whose influence spans national boundaries while policymakers remain constrained by domestic political pressures.

- Influence: Individual policymakers feel like they can be a force for good when they do good work on global catastrophic risk. For one to implement potential solutions, but also just simply by making the topic something that can get more easily discussed. One interviewee emphasized the importance of formative conversations with “people a lot brighter than me who are maybe going to end up in a sovereign wealth fund, maybe advising the government of Saudi Arabia or Abu Dhabi… If their framing of the world is just really, really slightly different and then they’re making a decision that relates to tens of billions of dollars being allocated in a particular area rather than on another.”

- Governance outside government: The idea here is that governance also happens a lot outside of government. This means we should not only rely on the policy world, but also work on creating more accountable governance structures in other places like academia or companies. As one expert on emerging biotechnology policy stated: “where I find the most optimism is where I dream of creating supplementary spaces that create bridges between regulation and scientists that sit just under regulatory decision-making that augment the process.” This reflects recognition that traditional state-based governance may be insufficient to control the institutional actors driving global catastrophic risk.

The research reveals a fundamental tension: policymakers understand the risks posed by concentrated institutional power, but feel constrained by the very power asymmetries this concentration creates. They see opportunities for influence through language, agenda-setting, and non-governmental governance mechanisms, yet remain skeptical about their ability to fundamentally alter the incentive structures that drive institutional bad actors.

Conclusion

The takeaway from all this is that large risks from individual actors is something we should be concerned with and prepare for, but the ultimate problem is not them, but some of the institutions which have been built to shape and control parts of society. Their incentives are often misaligned with society and we need more accountability and control over them. Policy makers are thinking about this, but it is just hard. The research shown here highlights that the actors posing the most risk globally are often held unaccountable and even the policy makers who think most about them, are unsure how they can make a difference. This means we need to restructure our system, so accountability exists again. And I might just sound like a broken record, but I think this is again an area where we can see that we have to make our society more democratic, that we have to experiment with new ways to distribute power. It might not fix all of our problems, but more decentralized decision making does lend itself less to unaccountable power centers by definition (6).

This post was reviewed by Mel Cowans. If you enjoy it, or are interested in any of the concepts discussed, feel free to reach out to them on Linkedin.

Endnotes

(1) This is especially the case for nuclear weapons, as the short time span to decide if you want to launch the weapons or not, makes it impractical to include a lot of shareholders. Kurzgesagt has a nice video which highlights this urgency: https://youtu.be/wmP3MBjsx20

(2) A more formal explanation of how this might come about can be found in Nick Bostrom’s vulnerable world hypothesis.

(3) As long as the person pushing the button is white, of course.

(4) Yes, I know that this is a newspaper article and not a paper, but I think it is a pretty good source and also includes lots of references to underline its arguments. You can also find a more detailed account of this in chapter 20 of Luke Kemp’s Goliath’s Curse book, which I summarized in another post.

(5) I have written about this here.

(6) See here for a more detailed argument why I think democracies are essential.

References

- Althaus, D., & Baumann, T. (2020). Reducing long-term risks from malevolent actors. Center on Long-Term Risk. https://longtermrisk.org/files/Reducing_long_term_risks_from_malevolent_actors.pdf

- Juergensmeyer, M. (2003). CHAPTER 6 Armageddon in a Tokyo Subway. In Terror in the Mind of God: The Global Rise of Religious Violence (3rd ed.). University of California Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt4cgfbx

- Kallenborn, Z., & Ackerman, G. (2023). Existential Terrorism: Can Terrorists Destroy Humanity? European Journal of Risk Regulation, 14(4), 760–778. https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2023.48

- Kemp, L. (2021). Agents of Doom: Who is creating the apocalypse and why. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20211014-agents-of-doom-who-is-hastening-the-apocalypse-and-why

- Meggitt, J. J. (2020). The Problem of Apocalyptic Terrorism. Journal of Religion and Violence, 8(1), 58–104. https://doi.org/10.5840/jrv202061173

- Nathan, C., & Hyams, K. (2022). Global Catastrophic Risk and the Drivers of Scientist Attitudes Towards Policy. Science and Engineering Ethics, 28(6), 50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-022-00411-3

- Sandberg, A., & Nelson, C. (2020). Who Should We Fear More: Biohackers, Disgruntled Postdocs, or Bad Governments? A Simple Risk Chain Model of Biorisk. Health Security, 18(3), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1089/hs.2019.0115

- Stevens, D., & Banducci, S. (2022). What Are You Afraid of? Authoritarianism, Terrorism, and Threat. Political Psychology, 43(6), 1081–1100. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12804

- Torres, P. (2018a). Agential risks and information hazards: An unavoidable but dangerous topic? Futures, 95, 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2017.10.004

- Torres, P. (2018b). Who would destroy the world? Omnicidal agents and related phenomena. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 39, 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.02.002