As long as we are not in the year 2100, we will not know exactly what path humanity will have taken when it comes to climate change in this century. But we can at least make educated guesses about the trajectory we are on. Given this, it seems that a good amount of climate science is aimed at hopeful temperature ranges below 2°C, which we will likely miss. The focus on below 2°C stems from the aspirational climate targets that humanity has set itself. We have less research on the currently most probable looking temperatures far above 2°C and even less on low probability, but high impact tail risk warming. By tail risk, I mean both the chance of unexpectedly high emissions and the chance of unexpectedly high temperatures from a given level of emissions. This post aims to give an overview of why I think that climate science is at least partly looking in the wrong direction to understand such risks.

Reasons for pathways above 2°C

First, let’s explore why it seems to have gotten more likely again that we will end up in a more than 2°C world. While there has been some hope before 2020 that climate action was gathering the force it needs to limit warming below 2°C, the last few years have had more of a feeling of disappointment in them. Both from the way the climate system is behaving, as well as how society is doing.

Green backlash

Before COVID hit, there were widespread climate protests in many countries. However, only a few years later it seems like the main news stories are that climate action is just too costly and we should abandon it and funnel all the money into the economy instead. This is not only my own impression, but also the topic of a recent review paper by Bosetti et al. (2025). They tried to understand the political consequences of climate policies. Based on their findings they argue that dissatisfaction around climate science mainly focuses on two issues:

- Economics: The distributional consequences. Climate policies, as all policies, produce winners and losers. If too many people think that climate policies will harm them, they will try to elect someone else.

- Culture: A broader pattern of distrust towards the scientific and political elite (1).

They summarize the overall process in a very straightforward conceptual model (Figure 1). The basic idea is politicians implement climate policies, these impact citizens, who elect politicians based on this impact. Easy.

Figure 1: Conceptual model of how climate policies, politicians and citizen preferences interact

They go on to explain all three steps of this in more detail:

Impact of climate policies

Climate policy typically involves two main components: promoting renewable energy and reducing fossil fuel use. Renewable energy projects often face local opposition, like people opposing turbines near their homes. Policies targeting fossil fuels include traffic restrictions, bans on combustion engine vehicles, increased fuel taxes, and coal mine closures.

Bosetti et al. (2025) find a consistent pattern across their case studies: these policies increase support for anti-climate politicians, but only when affected citizens receive no compensation. When compensation is provided, like improved public transport alongside traffic restrictions, support for climate action holds steady. People appear willing to accept climate policies when they’re compensated for losses and even more when they are included in decision-making. Unfortunately, these important steps are often skipped, as they cost additional money, which governments seem unwilling to spend. This compensation and representation gap typically benefits right-wing parties advocating against climate action.

Advocacy against climate action from populist right wing parties

Populist right wing parties particularly emphasize that there could be a trade-off between climate action and economic development, which is too high to pay. This is grounded in their belief that global warming is not actually that bad and a general opposition to higher taxes, often based on a neoliberal belief system. These messages allow them to frame climate action as a competition about resources between pure, working class people and corrupt elites, who only push climate action for their own gain. This messaging is often mixed with other themes like “climate hysteria”, which aims to discredit everybody who speaks up in support of climate action, as an overzealous activist.

There are some populist right wing parties (e.g. in Finland) who generally accept the claim that global warming is a reality, but are still against doing anything, as they frame it as unfair that they should pay, while others stand by idly. Similarly, it is often argued that one’s country is too small to make a difference, so only the major polluters are required to do anything.

Finally, climate action means change and conservative parties are all about maintaining the status quo. This argument is then pushed further by arguing that the country is in a pure and beautiful state (or more likely was) and that climate action will push it further away from this ideal.

Political consequences of the green backlash

We now know that climate action without compensation can trigger a significant backlash and that populist right wing parties are most likely to benefit from them. This has a significant impact on the likelihood of climate action decreasing or even being rolled back. The most prominent example here is Donald Trump. Besides many other things, he withdrew the US from the Paris Agreement (twice), defunded the Environmental Protection Agency and liberalized the drilling for oil and gas.

But we can see the same happening in Europe. Generally, the greater the influence of populist right-wing parties, the weaker the climate action. This impact increases if they manage to control a relevant part of the government.

Summing it up

Overall, this shows that we are currently in a time of slowing climate commitment, as exactly those parties who advocate against it, are able to gather momentum. However, as many of the grievances seem to be driven by a lack of compensation, this also opens the door for more successful climate policies in the future. But unfortunately, we do not yet live in this world.

Path dependence

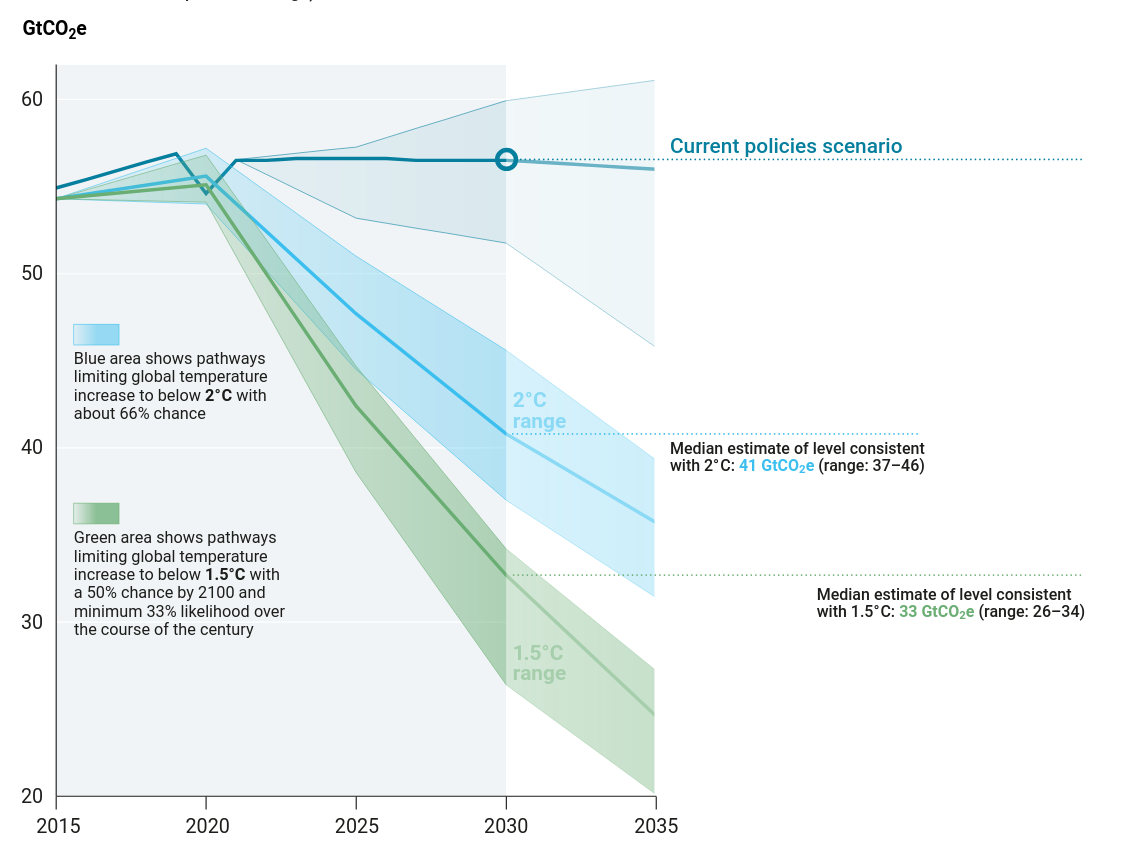

This rise of parties that are hellbent on delaying or stopping climate action has also shown up in the progress on climate action. If you have been involved in the climate movement or are interested in climate change, you probably have seen the kind of graph that shows past emissions and how much these would have to be reduced in the next decades to limit warming to 1.5°C or 2°C. You might have noticed that the slope of the emission reduction trajectory gets steeper every year, as countries fail to step up their climate game.

This pattern has become so obvious that there is even a whole UN report just about that topic (UN Environment Programme, 2023). In the report they review the state of emissions reductions and how it has developed over the last few years. Every year (with the exception of 2020 due to COVID) we set a new record in emissions, while the pathway we should be on points down, not up. Though, at least it seems that the emissions are growing more slowly every year, which implies that we should see them pointing down in a few years. But even if we see such a change in the direction of the trend in a few years, it will be too late to easily set us at a 1.5°C path again. The UN report also created an updated version of the graph (Figure 2) that shows the discrepancy between where we should be and where we actually are. This one clearly shows that we are very much on a pathway to above 2°C.

Though to be fair to the right wing populist parties who are currently working on dismantling climate action, progress wasn’t stellar before they showed up either. It is just that they slowed down the crawl even more.

Figure 2: Climate pathways for the next decades for current policies and what we would actually need to get to 1.5°C or 2°C degrees. Y-axis is the amount of gigatons of carbon dioxide we can emit.

Hot 2020s

While we seem to be living in a world where climate action decreases, at the same time the climate system itself may be responding more strongly than anticipated. Even if emissions trajectories stabilize, higher climate sensitivity or stronger feedbacks could push us toward higher temperatures than current models predict.

Here I want to highlight a recent study by Minobe et al. (2025). They argue that we are currently in a time where almost every new year is a new record in temperature. There no longer is a “normal” year. However, even in this more extreme world the years 2023 and 2024 have been extraordinary. Especially, oceans are severely affected by the rapid warming. To study this, they came up with a new statistical test which tracks abnormal-record breaking years and use this to analyze ocean and atmosphere data from 2023 and 2024. They find that these two years were warmer than we should have expected, even after factoring in El Niño events. This implies that we might be on a quicker climate pathway than standard models predict, might be caused by either climate sensitivity being higher than the median estimate or that feedbacks are stronger. In both cases higher temperature scenarios are becoming more likely. Though we need more data to be sure.

While this is just a single study, it is not the only one that has recently made the point that climate might be warming more quickly, as the last few years have been quite exceptional.

This implies we face dual risks: both insufficient emissions reductions and potentially stronger climate responses to whatever emissions we do produce. Both pathways lead to higher temperature becoming more likely.

Do we actually know what might happen in more extreme warming?

Temperature focus

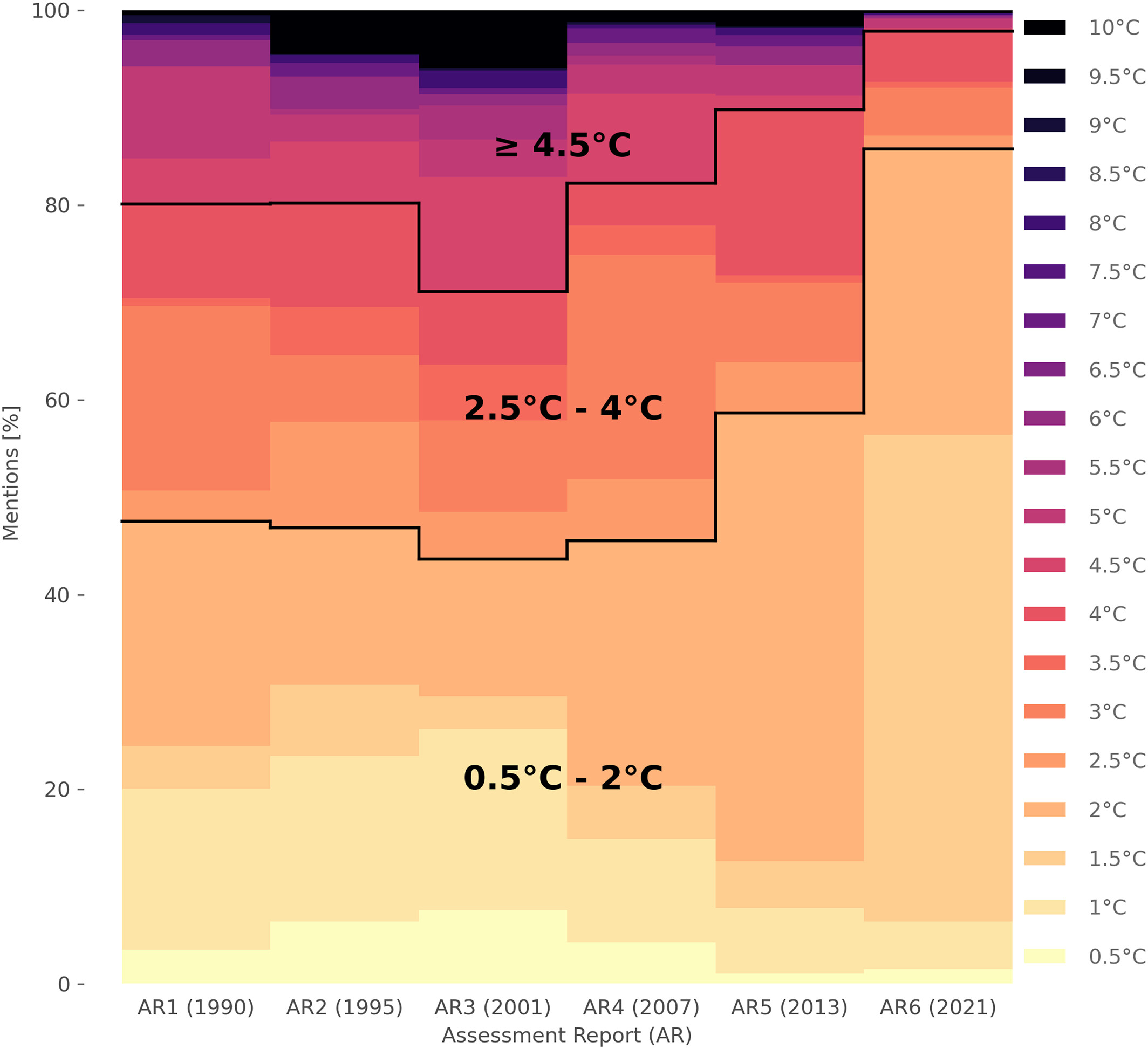

The three arguments I made above, a backlash to the green transition, slowing climate action and accelerating warming all point that we have a very good chance to end up well above 2°C warming. But how good are we actually prepared for that? Because theoretically, we all agreed that warming well under 2°C (or even below 1.5°C) is our collective aim as a species. As this was the agreed goal, there was also an incentive to focus just on those temperature ranges and scenarios that explore those. How much did this incentive shape research? This is the question that Jehn et al. (2022) tackle (Disclaimer: I am the first author on this paper).

The approach of the paper is simple: Read in all documents produced by the IPCC and track how often they mention different temperatures. The result is Figure 3.

Figure 3: Temperature mentions across the different IPCC assessment reports.

It shows that the range of temperatures explored always focussed most on temperature below 2°C, but really emphasized them in AR6, which was the first report after the Paris Agreement. This highlights that up until recently, most research energy was spent on temperatures we are quite unlikely to remain below.

Scenario focus

I am not aware of any study which updated those numbers using the IPCC documents published after 2022, but there haven’t been that many new documents anyway. But what exists is an interesting review and perspective paper by Meinshausen et al. (2024). In it they discuss how climate scenarios have been used in the past and how they should be used in the future. I am not going to recap the whole thing, because it is quite long, but what I want to highlight is that they find that we miss a suitable scenario that can be used, which is in line with the current promised policies. These will likely lead us to a world with far above 2°C warming, albeit with a high uncertainty. Past scenarios often explored temperature ranges higher and lower than this, but not really this pathway in particular. Meinshausen and co-authors therefore argue that in the future we should create such a specific scenario that starts from the place we are actually in right now. This would equip us with the knowledge needed for the pathway we will probably end up in.

This does not mean that we should all suddenly focus on RCP8.5 again, because this worst case scenario is practically impossible by now (2), but a more sensible approach to higher temperature and especially considering tail risk. This means the chance that we end up in a high temperature scenario, due to unforeseen feedback or higher than expected climate sensitivity.

Also, scenarios can only be a piece of the puzzle. What I think would be especially helpful is research around compounding and cascading events. The IPCC is quite good at pointing to things like the likelihood of extreme weather events increasing. However, what the research generally lacks is an understanding of complex cascades happening above 3°C. In such a warming scenario we can expect events like multiple-breadbasket failures, overstepping tipping points or large scale ecosystem collapse. What are the long term consequences of this? How might they interact? There is very little research about this.

Exploring tail risk is a good idea actually

The two last papers show that there is a clear gap in the research, both in the most probable bath, but also in more extreme warming. This means we need more research here urgently, to know what we are up against and what might happen if we get really unlucky. However, often when such catastrophic outcomes are highlighted as being worthwhile for research, they are often dismissed as only contributing to pessimism and climate inaction.

Thankfully, there is also a perspective paper by Davidson & Kemp (2024), which lays out why it is instead quite valuable to explore more extreme warming and that it is an essential part of good climate research and policy. They argue that by now there is plenty of evidence that exploring extreme warming does not misrepresent science. Also, there is no evidence that they slow decarbonisation or lead to apathy. There are even multiple studies that highlight that fear-based messaging is effective at altering intentions and behaviors, when they are framed as actionable.

They distance themselves from climate doomerism. They think of themselves and this approach rather as climate realism. Not seeing the more extreme futures as a certainty, but as a probability that has to be explored, to be safe from unpleasant surprises. Their motivation is to understand these futures better, so we can avoid them, not preparing for near term collapse (2).

They think there are three approaches which are most helpful to study these climate endgames:

- The first is foresight, which involves scientists, economists, and philosophers creating systematic assessments of catastrophic futures through tools like climate models, expert surveys, and forecasting exercises. While this approach aims to provide evidence-based probability estimates, it often falls short by using overly simplistic methods that miss important cascading risks and societal responses.

- The second approach is agitation, where political actors and activists use images of catastrophic futures to mobilize climate action. This includes warnings from groups like Extinction Rebellion showing that disaster is possible but avoidable. While agitation can effectively communicate stakes and counter false optimism, it risks depoliticizing the crisis by framing it as a universal threat that obscures different interests and positions.

- The third approach is fiction, where writers and artists create speculative narratives of climate-changed worlds. Climate fiction serves unique functions beyond entertainment—it challenges taken-for-granted assumptions through estrangement, offers reflexive commentary on how different communities already experience disaster differently, and reveals the limits of our ability to imagine unprecedented futures. While fiction may seem too speculative, it actually helps highlight important but overlooked futures and encourages epistemic humility (3).

The authors argue these three approaches are complementary and should be better integrated, while always maintaining awareness that extreme outcomes are uncertain possibilities to be avoided, not inevitable certainties to accept.

Conclusion

All this taken together it seems like we are on a challenging climate path of far above 2°C warming and we do not yet know enough about what might await us in such a future. However, it is great to see that people are working on this and it also was a pleasant surprise while reading the first paper (Bosetti et al., 2025), that apparently more climate policy does not automatically lead to more backlash. It just needs to be compensated and done more democratically for the outcomes to be much better.

Finally, I want to highlight especially the climate tipping points community. After many discussions and reading their papers, it seems to me that this is the part of the climate change community which takes tail risks most seriously. Also, they now publish their most recent knowledge now every year in a global tipping points report. It’s great to see that they are gaining traction in their research around more extreme futures.

Now we just have to put in the work to avoid those.

How to cite

Jehn, F. U. (2025, November 26). Does climate science focus on the right temperature range?. Existential Crunch. https://doi.org/10.59350/g64bp-jjf43

Endnotes

(1) If you want to learn more about where this distrust might come from, take a look here.

(2) Climate Brink wrote a nice explainer about why RCP8.5 is not likely.

(3) People mean a lot of different things when they talk about collapse. If you really mean collapse of industrial society, I don’t really see what preparation now will give you. Chances are really high you just work hard for the privilege to starve last.

(4) The best example of this is arguably “Ministry for the Future”. I can recommend asking climate scientists what they thought about the book. High chance they have read it and an opinion.

References

- Bosetti, V., Colantone, I., De Vries, C. E., & Musto, G. (2025). Green backlash and right-wing populism. Nature Climate Change, 15(8), 822–828. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02384-0

- Davidson, J. P. L., & Kemp, L. (2024). Climate catastrophe: The value of envisioning the worst-case scenarios of climate change. WIREs Climate Change, 15(2), e871. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.871

- Jehn, F. U., Kemp, L., Ilin, E., Funk, C., Wang, J. R., & Breuer, L. (2022). Focus of the IPCC Assessment Reports Has Shifted to Lower Temperatures. Earth’s Future, 10(5), e2022EF002876. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022EF002876

- Meinshausen, M., Schleussner, C.-F., Beyer, K., Bodeker, G., Boucher, O., Canadell, J. G., Daniel, J. S., Diongue-Niang, A., Driouech, F., Fischer, E., Forster, P., Grose, M., Hansen, G., Hausfather, Z., Ilyina, T., Kikstra, J. S., Kimutai, J., King, A. D., Lee, J.-Y., … Nicholls, Z. (2024). A perspective on the next generation of Earth system model scenarios: Towards representative emission pathways (REPs). Geoscientific Model Development, 17(11), 4533–4559. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-17-4533-2024

- Minobe, S., Behrens, E., Findell, K. L., Loeb, N. G., Meyssignac, B., & Sutton, R. (2025). Global and regional drivers for exceptional climate extremes in 2023-2024: Beyond the new normal. Npj Climate and Atmospheric Science, 8(1), 138. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-00996-z

- UN Environment Programme. (2023). Emissions Gap Report 2023: Broken Record. https://www.unep.org/interactives/emissions-gap-report/2023/