Life feels more rough, because it is. At least this is what I took as one of the main messages from Peter Turchin’s book “End Times: Elites, Counter-Elites, and the Path of Political Disintegration”. In it Turchin takes us on a grand tour of his structural demographic theory and how its insights can be applied to modern day America.

The mechanisms of structural demographic theory

The main idea behind structural demographic theory is that societies tend to regularly experience disintegrative phases and that the processes behind this pattern can be quantified and analyzed mathematically. How often you end up in trouble mostly is determined by how your society is set up and especially how many elites you have in comparison with how many positions you have for those elites. If an elite does not have a position that they think they deserve, they will use their powers to shape society in such a way that they get a position after all. This can quickly spiral into much disruption or even things like revolt or civil war, as those disgruntled elites often are open to quite drastic measures to get into power again. The number of elites is mostly determined by how many kids the elites had and by the inequality of wealth in a given country. When they have more kids and the money to educate them, elite numbers can rise quickly. Additionally, wealth means power and if you have much more wealth than almost anybody else, you can block others from positions of power, further increasing competition.

But before we dig into all this and how it currently plays out in the US, we first have to understand a few terms and concepts.

What are elites even?

Elite can be a vague term and people’s definition of what an elite is can differ. In the context of structural demographic theory an elite simply is a person who holds power in society. Especially in capitalist societies, the amount of power you have very strongly correlates with the amount of money you have. However, in addition to elites who wield power through money, you can also have elites who wield power by coercion (an army general), administration (the head of the central bank) or persuasion (your favorite celebrity). You can also have several kinds of power unified in one person. For example, economic power can be used to also gain political power.

The main mechanisms

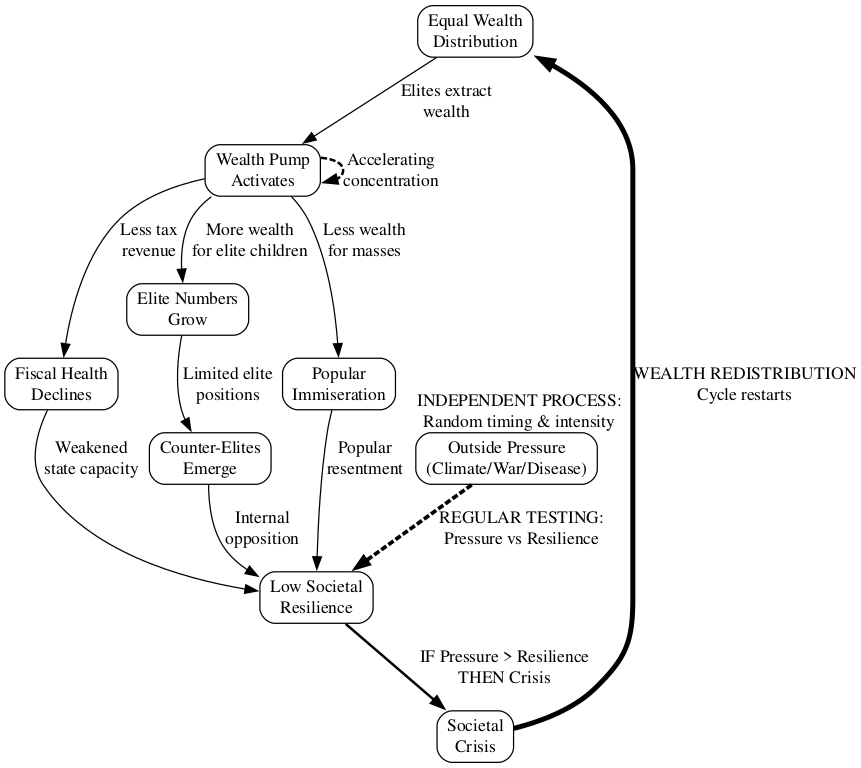

The wealth pump

One thing that elites tend to do is to extract wealth from the rest of society. While this is manageable at some level, if it increases over time you have a problem. Turchin use the term “wealth pump” for this, meaning that an ever increasing share of the wealth your society has is ever more concentrated in a small group of people. This increasing wealth concentration has several consequences.

Elite overproduction and counter-elites

The first thing is that you have an increasing number of elites. Because the easiest way to become an elite is to simply have rich parents. If the elites grab an ever increasing share of wealth from society, this means elites can distribute more wealth to more of their children. A second way to become an elite is upward social mobility. However, your society only has so many positions for those wannabe elites. Ultimately, only one person can be the president, no matter how many people would like to have this position. Therefore, the more elites you have, the more of those elites feel like they should be on top of society, but there is just no room for them anymore. These failed elites then become counter-elites, which means people who want to upend the current system, so they can get into an elite position after all.

To get back to a stable society again, you have to somehow reduce elite numbers again or expand the number of elite positions. Historically, this has mostly happened by overproduced elites simply being killed off in wars, purges, epidemics and the like. But there are also a few instances, like the New Deal, where this elite reduction happened by non-violent means and through re-distribution of wealth.

Popular immiseration

In parallel to elites getting richer, the general population gets poorer, because the additional wealth for the rich has to come from somewhere. When you get poorer, you usually also lose access to things that are valuable to you, think health care, education or freedom to do the things you want to do. This sucks, so people also tend to get less happy when they get poorer. Over time this builds up resentment in the population, which destabilizes society. This gets resolved once more of the societal wealth is distributed again to the poorer parts of society.

Falling fiscal health and weakened legitimacy

As wealth gets siphoned away towards the rich, this also means that the state gets less of it. However, to maintain public services, the state needs a certain amount of money. So, as the state gets poorer, it also loses its ability to provide for its citizens. You can actually see this in many present-day countries where public services have gotten worse and worse over the last few decades, as neoliberal politics reduced taxes and allowed more wealth accumulation in the hands of the few.

These deteriorating public services are a problem for your society, because it makes life worse for everyone and it also reduces the legitimacy of the current regime. If everything around you crumbles, the bus only comes once a day and your public swimming pool had to to close down, it gets difficult to feel like your society is making progress or moving in the right direction. This failure gets associated with the current regime and also partly with the way your society is organized in general. Like if you are in a democracy, and everything crumbles, people get the idea that democracy is not really working for them.

Outside pressure (geopolitics, climate, pandemics)

All of the three things I mentioned above (elite overproduction, popular immiseration, failing fiscal health) contribute to reducing the resilience of your society. The problem is that your society gets somewhat regularly confronted with outside pressure. This can be climate (a drought), a pandemic (black death) or a neighbouring state deciding that they want to wage a war against you. Your society does not really have much control if these things happen and on what magnitude. This means we can imagine your society as having a certain resilience value, based on how well it manages elite overproduction, popular immiseration and fiscal health. This resilience value is then tested by outside pressure on random times and in a random strength. If the pressure is larger than your resilience, you collapse or at least have a major societal crisis. This means even very resilient states can fail when they are challenged by a large outside pressure, but also that very fragile states can last for a long time if they get lucky. If you collapse or have a big crisis, this usually resets the wealth distribution in your society and the cycle can start anew.

Figure 1: Flow chart of how the basic mechanism of structural demographic theory works.

Additional mechanisms

Besides this main loop of structural demographic theory, Turchin also describes a bunch of other processes which can happen and which reinforce the loop or explain parts of it better.

Goldstone’s theory of ideological change

In addition to the main structural demographic cycle explained above, there are also other mechanisms at work. One of them is how the ideological landscape fractures once there are too many elites. All of these failed elites try to push their narrative of why the country is struggling and why it was not able to provide them the elite position they deserved - typically with themselves placed as leaders of these splinter ideological camps. The phases of how this fracturing developed were described by Jack Goldstone. He thinks the fracturing cycle happens in three main steps: The state struggles to maintain the power over the societal narratives, as more and more counter-elites try to push their narratives. Once the old regime has lost legitimacy completely (in the past often accompanied by collapse), the different factions in the counter-elites fight for the authority over the remaining society. One of those fractions wins the authority, which allows them to suppress the other narratives by reconstructing new political, religious and social institutions.

The ruling class

Who controls society? A question often asked, and often answered very differently. In many early states the question was easy to answer. Those who controlled the military, controlled the state. But over time persuasion became a much more important factor. It is much better to convince others that helping you is in their self interest, then forcing them at gunpoint. In the past this was often done through religion. This is the reason you find so many god kings in history. They merge the power of coercion and persuasion. Religion is also still used today, like in Iran where the regime clearly builds its power on religion, but also in the United States where many things are still justified using Christianity.

In many countries today, the military is still an important factor, but in most mature democracies the military is not really a power factor anymore. Especially in the United States if you belong in the ruling class or not is based on your wealth. Running for office is so expensive now that only independently wealthy or highly sponsored politicians even have a chance in the race to get elected.

The motives to get to power are quite obvious here. Most people want their wealth to grow rather than diminish. This seems to be especially the case for the rich in society. But while they might try to have policies implemented that profits them in some way, there is no big overarching plan. Just many small interactions of the wealthy interacting with the policy makers. Over time aligns the interest of society with their interest. This also means there is no power center. Just 1000s of rich individuals follow their own incentives, but as a whole class they push society towards their collective needs. And none of this is a secret. There is no hidden kabal. Just people following their incentives, which unfortunately leads to bad societal outcomes.

How structural demographic theory plays out in the United States

The two narratives of American society

After we now have the basics of structural demographic theory down, we can look at how all those processes play out in the United States. In the United States there are currently two main narratives of how the country explains itself to itself, think slogans like “The system abandoned the white working class” versus “The data proves life is better, the bigots are just mad about losing privilege”. Both groups who tell these narratives think that the other group is one that is really destroying the country they love.

The first narrative is those of the poor, white working class. For them their life just got worse and worse over the last few decades. Everything in their life is on the cusp of breakdown, their health, the infrastructure around them, everything crumbles. This leaves them frustrated and especially when other people call them privileged for being white. They don’t feel privileged. Don’t the others see that they are barely hanging on?

The other narrative is that the last 100 years of the United States have been a clear success story. The life of everyone is getting better (just look at the “Our World in Data” graphs!). If you work hard, you can get rich and live the life you always dreamed of. If you are poor or your life just does not come together, it is just because you did not work hard enough. If you would really be trying, you would be thriving. If people claim that things are getting worse, they are simply rejecting scientific data. Why can’t they see that they are so obviously wrong?

What are the trends in the United States when it comes to societal outcomes?

The tricky thing with both of these narratives is that they are partly true and partly wrong. Both are anchored in reality, but only in a part of it, only for a certain group. Life in the United States really has gotten significantly better over the last decades, but only for the richest 10% or so. The vast majority of people however, are worse off than their parents. GDP might be rising, but if the real wages decline each year, this just means that the majority of people get poorer even as the GDP is rising. Two thirds of the American population earn less in real wages than their parents did, while at the same time costs for the basic necessities of life like health, education and housing have all gone through the roof. This makes getting it even harder to get the education you would need to even have a chance of making it. All of these trends have been especially strong for men and Black Americans.

We can find the effects of this even in the physical and mental health of Americans. Since the 1960s Americans have not been getting any taller, while other rich countries continued to grow in height. Even more stark is the trend reversal in life expectancy. It has been on a downward trend in the United States since around 2013, while also still climbing for other rich countries.

This tough situation for many Americans is also mirrored in how they cope mentally. Over the last decades the deaths of despair have been rising. These are deaths caused by suicide and drug abuse. Here too the burden is especially high on middle aged men with little education.

So, we see life in the United States can be great, but only if you are rich. If you are in the majority of the population, life in the United States is hard and has been getting harder for decades. But how did the United States even end up like this?

Historical causes for the mess the United States are in right now

The plutocratic roots of the United States

Around 1500 plutocracies were quite common in Europe. However, pretty much all of them were conquered by militocracies in the few hundred years afterwards. This constant pressure of warfare weeded out the states that could not fend for themselves and it turned out that states run by the wealthiest members of society just weren’t very good at that. However, we had one exception in Europe, where plutocratic rule could be maintained: England. England was able to maintain only a relatively small army by being an easily defendable island. This was enough to deter most attempts to conquer the island. And this rare plutocratic state was one major contributor to the colonization of the American continent. This gave the United States strong plutocratic roots. And as the United States also ended up in defendable territory, with neighbors militarily weaker than itself, it never really had to give up on plutocratic rule.

The American Civil War

Before the American Civil War there was discontent brewing in the United States. The center of power were the aristocratic Southern slaveholders in combination with Northeastern merchants, bankers and layers. The South produced the agricultural goods and the North made sure to sell it all around the world. In this arrangement, the South was generally more important, as the structure of the United States at the time led them to control half of the Senate, even though they had a lower population. Also, most of the richest Americans all lived in the South.

In the decades before the civil war you saw several signs of things getting worse. The relative wage declined, there were more urban riots and the number of millionaires skyrocketed. As the country industrialized the Northern elites got richer than the Southern ones and increasingly disliked that they had more money, but less power. They wanted to reform the state in a way that was better to their business interest. However, these reforms would have been to the detriment of the South, which therefore blocked it. As the conflict lines deepened, you also had more elite overproduction in parallel. It was caused by industrialization creating sustained economic growth while labor oversupply (from rapid population growth and immigration) kept worker wages stagnant, directing all the fruits of that economic growth to the wealthy class instead. We can also see more and more violence being done (like more riots and people having fist fights in the Senate), the closer we get to the outbreak of the civil war.

While the general story of the American Civil War is that it was fought to free the slaves, Turchin thinks this is only a fig leaf for the real reason: Slavery was the economic foundation of the Southern economy. If you remove slavery, the South would decline in importance and thus the Northern elites could do what they want.

Racism kills solidarity

One major hurdle to end plutocratic rule in the United States was racism. In many European countries you had large socialist movements, which united all of the working class and gave them strong leverage to push for change. Even though much of the gains from these days have been scaled back again in Europe, they pushed harder than the United States and managed to slow down scale back more efficiently. The working class in the United States often failed at this, because they were split by racism. The plutocratic elite could use racism to drive a wedge between black and white workers. This decreased their bargaining power and left them in a worse position than their European counterparts. Due to this, the American workers never managed to force so much redistribution as in Europe and the plutocratic elites could maintain their position.

The reforms of the Progressive Era

Still, we can see that the labour movement in America was able to achieve some wins during the Progressive Era (roughly 1890s to 1920s). What changed during the Progressive Era? Several factors converged to force even American elites to make concessions. The two decades around 1920 saw unprecedented crisis pressure: nearly four million workers struck in 1919 alone, the Battle of Blair Mountain became the largest armed insurrection since the Civil War, and race riots killed over 1,000 people during the “Red Summer.” This wasn’t periodic unrest, it was a sustained threat to the entire system. External events like the Russian Revolution provided additional pressure, showing that entire systems could collapse if they lost legitimacy.

Crucially, elites realized they could make strategic concessions without abandoning their fundamental position. The immigration restrictions of 1921-1924 reduced labor oversupply and boosted wages, but business elites accepted this constraint because it helped stabilize the system. Progressive reforms often worked around racial divisions rather than challenging them directly, like focusing on white-dominated industries while reinforcing certain racial boundaries. These kinds of compromises brought some peace to society and laid the groundwork for the New Deal.

The New Deal almost turned the country around for good

The New Deal reshaped American society towards more redistribution of wealth. It had become possible because in the decades before, discontent had been rising sharply again. More and more labor conflicts of which an ever higher percentage also turned violent. Sometimes even resulting in federal troops being sent in to kill striking workers. The New Deal didn’t overcome racism - it temporarily sidestepped it by explicitly excluding Black Americans from the social contract, just like in the reforms of the Progressive Era. This morally compromised arrangement enabled white working-class solidarity by removing the racial economic competition that plutocrats had previously exploited. Additionally, the severity of the Depression crisis made some elites willing to accept significant redistributive policies to prevent complete system collapse.

At the same time, you had strong ideologies pushing for change all over the world. Anarchism, communism and facism all represented themselves as an alternative to capitalism. This danger coming both from within and without forced the American elites to acknowledge that something had to change. This change was the New Deal. It introduced that the rich had to pay considerably more in taxes and that this income would be redistributed to the poor and built up the infrastructure of the United States. These policies decreased wealth inequality without any bloodshed, thus decreased elite overproduction and popular immiseration and led to several decades of social peace.

One of the most important outcomes of the New Deal was an unwritten contract between business, workers and the state. It gave workers the right to organize and bargain collectively and that the gains from economic growth would be shared with everyone in society. A social cooperation between commoners, elites and the state.

Breakdown of the consensus on how society should look like and the rise of Reagen

While the New Deal brought peace to American society for a few decades, this all started to come apart in the 1970s and 1980s, but the roots of this can already be found in the 1950s. If you track how far away from each other the Democrats and Republicans are politically, you see that around the 1950s they started to drift apart, with the left wing people sorting themselves into the Democrats and the right wing people into the Republicans. This sorting and thus the political polarization have only been going up since then. By now both parties’ more extreme wings argue for a complete restructuring of society. This means we are in the middle of the ideological change cycle by Jack Goldstone which I described above.

A clear break from the New Deal consensus can be seen especially in the 1980s. The people coming to power at that time, exemplified by Ronald Reagan (1), started to dismantle the pillars of postwar society, guided by a new economic theory, neoliberalism, which argued that rules and redistribution are bad and that capitalism should be unchained. This disruption is when we see the start of the decline of real wages. The ideas of neoliberalism were supported by neighbouring anti-collective ideas like objectivism and meritocracy. These argued for egoism actually being good, collective action being bad and how rich you are only reflects how hard you worked and nothing else (2). All of these ideas are excellent if you really want to make the wealth pump go brrrr (3), but not that great if you want to have a stable society for the long term. It might be able to pump up your GDP, but what is a high GDP worth if people die earlier each year?

Everybody goes to university now

As all of these processes jacked up the wealth pump, it predictably led to an overproduction of elites. In the 1950s around 15 % of the population went to college. In the United States of today, it is around two thirds. This means, even if you are really good, your chances of making it to the top are slim. This leaves a lot of people frustrated. Wasn’t the idea that education would make sure you get your share of the pie? In the American system this gets worsened by the high amount of student debt that people accumulate while getting an education. Not being successful after going to university hurts even more if you are crushed by debt afterwards.

This higher competition between elites also leads to more cheating and other anti-social behaviour. This happens because people get more desperate, when they realize the competition is so high that they probably will not make it, no matter how hard they try. It was further emphasized by philosophical ideas like objectivism, which tell you that it is fine to only look out for yourself.

No political influence for the poor

All these forces have led to ever diminishing influence of the poor in American society. If you have money, you can easily influence the public opinion, by pushing your narratives in the media. Also, you can invest in lobbying and buy your access to politicians directly. There is an extensive piece of research about this by the political scientist Martin Gillens. He gathered thousands of policy issues between 1981 and 2002. For each of those issues he checked what was ultimately decided and how public opinion was thinking about the issue. He found the political outcomes in the United States only aligned with the interests and wishes of the richest 10 % and their interest groups. Everybody else’s preferences were simply not reflected in national policy decisions. This is a consequence of decades of shifts in wealth in power in American society.

So, what can we expect for the future?

Given the trends we have seen above, what might the future hold for the United States? Turchin is relatively pessimistic here. He thinks that the 2020s are bound to be a rough time, no matter what we do now. The problems are just too deeply entrenched to quickly resolve them. The first chance he sees of conditions getting better are the 2030s, but only if we manage to lay the groundwork for this better trajectory now (4). To get to this better future, the United States has to find a way to break free again from their plutocratic rule, just as they did during the New Deal. If they don’t manage this Turchin predicts that things will only get worse, with ever more violence and disruption. This could get as bad as a new civil war.

But who might bring about this change? The problem in the American society of today is that pretty much all of the elites are still deeply entrenched in neoliberal economic ideas. Up until recently the main political fights in the United States were all centered on culture war issues (and it is still a major focus). There was little disagreement about most of the economic policy between Democrats and Republicans. But on the edges of both parties, there are dissidents who think about how things might be done differently in the future.

The dissident left is centered around people like Bernie Sanders or Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. They think about more socialist ways to organize the American economy and are the reaction to the abandonment of the working class by the Democrats under Bill Clinton. The dissident left had their chance to power when Bernie Sanders almost became the presidential candidate, but they were overpowered by the more established, neoliberal Democrats. Since then, the dissident left did not have much to celebrate. Their cultural ideas are much discussed in the form of culture war, but their criticism of existing economic and military structures rarely finds its way into mainstream media.

The dissident right on the other hand has been much more successful over the last decade. They found their champion in Donald Trump. While Trump sees himself as a classic elite, many of his followers and allies (like Steve Bannon) see themselves as a revolutionary force (counter-elites). Their first attempt to dismantle the system after the election of 2016 failed. However, instead of assimilating into the ruling class, they became more radicalized by this experience. This radicalization has spread to the Republicans in general and by now a large chunk of them have taken up the ideas of the dissident right. Some of the ideas are even aimed against the interest of the plutocratic elite, like tariffs for example. But mostly they just seem out for disruption and domination. The big question is: How successful will they be in their second attempt to break the current system?

Obviously, Turchin cannot answer this question and the history of future America remains to be written. However, he points to history again to give us an idea of how things might play out. When we look at historical crises, it becomes clear that most societies follow a very similar path into crisis. Specifically, the one described in structural demographic theory. The wealth pump activates and things go downhill from there. However, once the actual crisis starts, things get interesting. Because here, history shows that the path of societies diverge again and every society seems to map out their own unique path on how they resolve their crisis. Unfortunately, history also shows that in the vast majority of examples, the crisis is not resolved peacefully, but by the horsemen of the apocalypse. But still, there are at least some examples in history where societies were able to solve their problems peacefully. Turchin thinks the best examples here are England in the Chartist period, (1819-1876) and Russia in its Reform Period (1855-1881). Both countries used peaceful reform and a redistribution of wealth from the rich to the poor to bring back societal stability. Or even in the United States we can point to the New Deal as an almost successful example of making society more equal again for the long term.

This means there is hope that we can resolve the crisis of the future peacefully as well. Europe will be interesting to watch here, as we have many nations with a relatively similar structure and environment, but wildly differing levels of inequality. It will be a good test case for the idea that low inequality makes societies more resilient.

Conclusions

At first glance, this book does not offer you much to hope for. It mainly seems to say that times are tough, and will remain tough for the foreseeable future. If we move things in the right direction, they might get a bit better again in a decade or so. If you look a bit more closely, it offers at least some glimmers of hope. It tells us that reform is necessary, yet often fails, but it also highlights that there are some examples, like the New Deal, where successful redistribution was archived (for some time at least). And in contrast to past societies, we now have at least some understanding why societal crises happen and what might be done about them. But what I found perplexing about this book is how timid it is in its recommendations about what might be done. It hammers home again and again and again the point that wealth accumulation of the rich is the main process that drives instability in society. Yet, it does not call for a complete restructuring of society or taxing billionaires out of existence. It merely suggests we should work towards something like the New Deal again and hope for the best. But if we take the book seriously, shouldn’t it argue for a whole new way to structure society? Come up with ways that never again allow the wealth pump to run its course?

I would say yes, this new structure of society is exactly what we should be looking for. But why are you even listening to me? I am just a scientist who did not manage to get a permanent position at university and now I write a blog for a living. According to this book, this makes me a counter-elite who just tries to push their narrative to get power in society again. So, maybe take it with a grain of salt. But I suspect many are feeling like something fundamental needs to change, even if we can’t quite put our finger on what.

Appendix

I wrote those sections, but had to cut them, as they were in the way of the flow of the post, but they were just too interesting to not include them here.

A brief history of quantitative history/Seshat/Structural Demographic Theory

The idea to quantify history is actually quite old. The trouble is that doing it is very hard, which left most previous attempts going nowhere. Turchin traces back the roots of the theory to Jack Goldstone. While Goldstone had some initial success in understanding history using large datasets, he did not get much recognition and struggled with a lack of structured data, which could be used to make the big historical comparisons more accurate. This is the place where Peter Turchin comes into the story. He got to know Jack Goldstone and the two started collaborating. This collaboration was an inspiration for the creation of the Seshat database (which I have discussed on this blog on several occasions). This database contains a vast treasure trove of quantified historical data. All in the same formats, so it can actually be compared and analyzed statistically. This allowed the ideas of Goldstone to really shine, because now the data was available to make more solid analysis and predictions. To create such datasets is actually quite involved. It took them 7 years from starting to collect data to the first published paper. The Seshat team consists of people with a wide range of expertise from anthropologists, historians, archeologists and data scientists. The data they find is coded by research assistants, this codification is then checked by other research assistants and more senior researchers, as well as by experts in the relevant fields when the coding is difficult/ambiguous. This means every data point in Seshat had several people look at it and verify it and the more complicated ones always had an expert involved. In my opinion, this is the best historical data source out there and if you reject Seshat, you also kinda have to reject all other historical empirical claims, as Seshat is the biggest one. If you don’t trust this one, it would be weird to trust smaller ones.

Plutocracy versus democracy versus autocracy versus militocracy versus theocracy

You can structure your society in a lot of ways, but one of the most important factors is the question of how power is structured. A plutocracy is a system where the wealthy elite hold political power, with governance effectively controlled by the richest individuals or corporations. Democracy involves rule by the people, typically through elected representatives who are accountable to citizens via regular elections and civil liberties. An autocracy concentrates power in a single ruler or small group with no meaningful checks on their authority, often suppressing opposition and dissent. Militocracy places military leaders in control of government, where armed forces directly govern rather than serving civilian leadership. A theocracy is ruled by religious authorities or leaders who claim divine mandate, with laws and policies based on religious doctrine rather than secular principles. Each system represents fundamentally different approaches to organizing political power and determining who has the authority to make decisions for society. There is often also no clear cut between them and you can have things like an autocracy which still conducts elections, which are at least somewhat competitive, but strongly titled towards the rulers.

Historically, militocracies and theocracies were quite dominant and often intertwined, but nowadays it is mostly plutocracies, democracies and autocracies we end up in. To highlight how even similar countries can end up in different spectrums of this, Turchin compares the fates of Belarus, Russia and Ukraine after the fall of the Soviet Union.

Russia

After the Soviet Union crumbled, Russia implemented privatization on a breakneck speed. This served the plutocratic elite well, because they could amass tons of money. This money in turn allowed the rich to influence politics on a massive scale, quickly turning the country into a plutocracy. However, this got so bad, so quickly that the remaining elites in the military and administration realized that they had to do something, or lose all of their wealth and power. They used their remaining power to place Putin in the role of president. While he and his allies were corrupt. They were less corrupt than the plutocratic elites they ousted. This stabilized the country and life became better again for many Russians. This in turn meant when large protests broke out against an ever more autocratic regime, they did not gather enough momentum. Too many people felt that things were going in the right direction and did not want to rock the boat. This allowed the autocrats to consolidate power even more and turn Russia into a full fledged autocracy.

Belarus

When Belarus became independent, the first election was won by Alexander Lukashenko. He saw how the total privatization in Russia had wrecked the economy, so he opposed the same moves in Belarus and kept the key industries under state control. As he controlled the state and the state controlled all key industries, he could use this to gather favors. He focussed on the military. This served him well when large protests broke out against him in 2020, because he could use his contacts in the military to crack down hard on protesters. He was also strongly supported by Russia. This now leaves Belarus somewhere on the border of an autocracy and militocracy.

Ukraine

In contrast to Belarus and Russia, in Ukraine the rich could maintain power for much longer. The other elites in society were not able to hold up against them, which allowed the start of a massive wealth pump. This was partly due to Ukraine being much more split between east and west. Roughly half of the country wanted to join the EU, while the other half wanted closer ties with Russia. This meant that there was no unified power base against the control of the rich and several revolutions just led to another plutocratic faction gaining power. They were able to siphon away much of the wealth of the country, leaving Ukraine with half of the GDP per capita than Belarus, but a lot of billionaires. This streak of plutocratic rule ended when Viktor Yanukovych took power. He was massively corrupt and tried to steal both from the public and the other oligarchs. This was such a blatant power grab, that it allowed enough forces in Ukraine’s society to unite to remove him from power and elect a new president. As Yanukovych was very pro-Russian, his removal also meant that Russia feared it would lose influence in Ukraine. Therefore, the revolution was also the trigger of Russia getting more involved in Ukraine’s politics, which first led to the civil war in the Donbass and ultimately to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. How the country will go into the future very much depends on how the war ends. If it does not end in a total disaster for Ukraine, there is a good chance that it will lead to a more democratic Ukraine, as the war has reduced inequality by destroying much of the wealth. Also, the Ukrainian people are really fed up with having large political influence by both Russians and plutocrats.

How to cite

Jehn, F. U. (2025, October 1). Inequality all the way down. Existential Crunch. https://doi.org/10.59350/3zhee-h1x35

Endnotes

(1) It’s always Ronald Reagan isn’t it? I feel like every time I read about this guy it’s “Ronald Reagan got elected and X started to get worse”.

(2) This is your regular reminder that the later Ayn Rand relied on the very Social Security and Medicare benefits she spent her career arguing against.

(3) Are people still making this joke?

(4) Or more like yesterday, as the book was published in 2023.