When we study societal collapse, we typically examine it through the lens of elites. Using the records and remains left by emperors, nobles, and the literate classes who had the most to lose when their world ended. But what if we’ve been asking the wrong question all along? After years of reviewing collapse literature ranging from quantitative databases like Seshat to case studies spanning millennia, certain patterns emerge again and again. When I encountered Luke Kemp’s “Goliath’s Curse: The History and Future of Societal Collapse” his analysis aligned with many of the conclusions this blog has been exploring: that inequality drives fragility, that democratic participation enhances resilience, and that our current global system may be more vulnerable than it appears. But Kemp adds an important perspective that most collapse research overlooks. He challenges elite-centered views of history. Rather than simply asking why societies collapse, he asks whether collapse is necessarily the disaster we assume it to be. Perhaps the real question isn’t why collapse is so catastrophic, but catastrophic for whom?

How bad is collapse and for whom?

Societal collapse is usually seen as a bad thing. It implies chaos, violence and misery. And this is certainly true for some part of the population, but not for everyone. Historically, most states were quite horrible to live in. For example, both the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire were at war for the majority of their existence, while also keeping a large chunk of its population as slaves. Even for a normal farmer, life often wasn’t great. You had to pay a lot of taxes, while often not getting much in return. So, for the average person in the Roman Empire, your life had a high chance to end in war, poverty, or slavery. But this isn’t the Rome we often remember. When we think of Rome we think of all the monuments they build, the art they produced and their politics. But these aspects are representative only for a small sliver of the inhabitants of the empire. We talk about the cultural accomplishments instead of the war, poverty and slavery, because history isn’t written by a poor peasant in the alps or a slave in the mines in Spain, but by the rich, the landowners, the priests, the politicians. This is the case for pretty much every empire.

We see societal collapse as this uniquely bad thing, because we take the accounts of the richest people of the past as representative for the whole population. But what does collapse look like if we instead focus on the living conditions of the average person? What if we have a people’s history of collapse? This is the question that Kemp’s book is trying to answer.

This does not mean that Kemp thinks that collapse has no downsides. It can surely have horrible consequences. For example, if you have a region that specialized in a certain crop, to trade it with other parts of its empire for everything it needs, this region will have massive problems when long distance trade ends because an empire has collapsed. But still, for many of the poorer people, this collapse might mean the end of slavery and a general betterment of their living conditions. The effects of collapse strongly depend on where you are and also when you are, as the consequences of collapse have changed over time as well.

The state of nature?

When we think about what human life was like before we started to record our history, there is one quite dominant idea: the state of nature. The state of nature was an idea made iconic by the philosopher Thomas Hobbes. It assumes that human life before states were established was nasty, brutish, and short, due to humanity being locked in a war of all against all. We therefore need a social contract between the state and its citizens. The state provides order, while the citizens submit to the state for their own protection from each other. While this view on humans is quite popular (especially on the right side of the political spectrum), it is not actually grounded in any data. Hobbes just extrapolated from his personal experience of living through a civil war and concluded that this has to be true for all of humanity. The great thing is, we now have data to verify these claims and this data paints a very different picture to what Hobbes had in mind.

Before humanity started to live in permanent settlements, egalitarian bands of up to 200 hunter-gatherers roamed the lands. We know they had regular exchanges with other bands, because the remains of these groups have quite a high genetic diversity. But genes weren’t the only thing they exchanged. We can also find evidence that they conducted long distance trade 200,000 years ago, transporting goods like obsidian or shells for around 200 km. They also had communal projects, which brought together thousands of people. The most famous example here is Göbleki Tepe. A massive temple-like structure which was built by cooperating hunter-gatherer tribes.

But not only did humans cooperate and trade over long distances, their life also wasn’t nasty, brutish and short. Instead the evidence we find for violence is generally pretty low, albeit highly variable. Looking at anthropological evidence from hunter-gatherers we find values between 0 and 55 %. However, these studies are unreliable with the violence coming from settlers, farmers, and the effects of alcohol. In the archaeological record, the largest systematic studies have found signs of only around a 1. % lethal violence rate throughout the paleolithic. Almost all the deaths are attributed to one site: Jebel Sahaba, which saw a surge of violence during the environment tumult as the world exited the ice age and entered the stable warm period we now know as the ‘Holocene’. Lethal violencerates today are 0.9 %, or 2.2 % if you include suicide. What is also striking about these findings is that we basically see no warfare in the evidence from hunter-gatherers. If there was violence, it was likely between individuals, not between groups.

Our egalitarian origins

This relatively peaceful existence was likely possible, because humans are quite egalitarian in their origin. Only around 11,000 years ago do we see the first consistent markers of hierarchy, like bigger graves or larger houses. Present day nomadic hunter-gatherers still maintain an egalitarian lifestyle. They make sure that everyone who tries to dominate the hierarchy is brought down again. First with social pressure, but they even go so far to kill members of their tribe, if that member continuously tries to raise themselves about others. This dominance aversion is made also easier by a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. If somebody tries to dominate you, you can simply move somewhere else. We can also see this in our biology. Human males generally lack the attributes that species usually have with steep dominance hierarchies, like males being much larger than females and having natural weapons like big and sharp teeth. Additionally, our eyes are much more white, than gorillas or chimps. This is likely an evolutionary adaptation, as it allows others to gauge what we are focussing on, therefore making our intentions more obvious to others, which builds trust.

But in addition to this egalitarian streak, we are also obsessed with status. This also makes sense from an evolutionary perspective. If your status in your group gets too low, the group might expel you, which would mean certain death in many environments. But also, the higher your status is, the more likely it is that people will give you what you want.

When we think about status there are generally two ways you can get it: dominance or prestige. These have quite different implications. Prestige based status is the more prosocial and helpful version. It helps the whole group if people who can do something particularly well get more status. Also, status based on prestige cannot be really inherited and you therefore do not have accumulation of status over generations. Dominance on the other hand is seizing status by sheer force. It is based on violence, intimidation and controlling resources. If possible humans usually try to avoid individuals who seek status by dominance, while seeking those who build status by prestige. Not all individuals have an equal desire for status: a desire for status through dominance is higher in men and those who rank higher in the dark triad.

Our origins seem to be shaped by people seeking prestige and cooperation in an egalitarian setting. Unfortunately, this all started to change once humans started to gain access to new resources.

The birth of Goliath

The idea of societal collapse is only really applicable to humans once we settled. While hunter-gatherers fluctuate widely in their population numbers, these were driven by other processes than what we usually consider to be a societal collapse. Their number waxed and waned in direct correlation with the general productivity and climate of the region they stayed in. When the climate got cooler and productivity fell, so did human population numbers. While these are factors that also influence settled humans, they can maintain higher population numbers for longer, even in more adverse settings, because they can create a storage for emergencies. Hunter-gatherers had on average a much better diet than agriculturalists. However, they also had more periods of famine and starvation. This means when you settle down and focus on a single ressources, you are worse off on average, but shocks don’t hit you as hard.

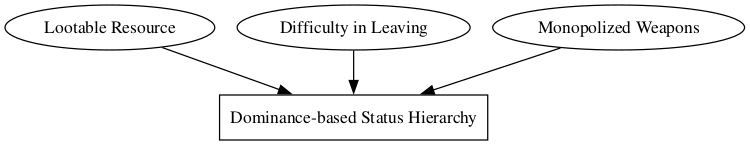

Creating a settlement only makes sense when you have some abundant resources nearby. These can be fertile farming lands, but any reliable resource works. Many of the first settlements were founded near naturally abundant places, like rivers with plenty of fish. While this made humans more resilient to the fluctuation of the planet, it also allowed dominance based hierarchy to creep in. Though the surplus in and of itself is not the problem. The tricky thing is if the resources could be easily seen, stolen and stored. If you combine with caged land and monopolised weapons Goliath can rise. Once you live for generations at the same place and you focus all your lifestyle around a few key resources, accumulating wealth becomes possible. And once you have more resources than others you can trade them for power.

Imagine a fishing village. One family finds an especially plentiful place to fish and is able to make it storable (e.g. via smoking). This means they can accumulate more fish than the others. This gives them opportunities like hosting a feast or helping out others in times of need. These opportunities create a social debt which is owed to that family. They can leverage this social power to shape the decisions made in the village. To make this work, they not only have to gather these extra resources, they also have to make sure that nobody else takes them. To defend your resources, you need weapons and people to wield them. If somebody objects to this, there is not much they can do. They cannot easily leave, as their life is centered around the local resource as well and they cannot challenge the leading family, as they control the weapons and the social power in the village.

We started with a family that gathered a bit more fish than the others and ended up with this family now having a small militia, while everyone in the village owes them a favor. This showcases how dominance based status hierarchy easily develops once you have a storable resource, people cannot easily leave and monopolized weapons make it hard to resist. Finally, these resources and dominance structures can be easily inherited, making it easier to build and refine them across generations.

Figure 1: The recipe for dominance based status hierarchies

This does not mean that we always have to end up in this situation, just that it is a strong natural attractor in the space of ways to organize your society. This is what Kemp calls Goliath: a collection of aligned dominance based hierarchies across different areas of life which control labor and energy.

Once a Goliath is established, it aims to accumulate more and more resources. This tends to increase violence. Both in and between societies. It increases in the societies, as the dominance has to be enforced to keep people in line and it increases between societies, as other societies represent a threat, which could be solved best preemptively. This clearly shows in our archeological evidence. Violence increases across the board and we also see mass killings and human sacrifice, which basically did not exist before. This means Goliath has shifted the focus from between individuals to between groups and therefore is the origin of war. We see this empirically in Japan, Europe, Mesoamerica, China, North America, and the Near East.

Collapse in the first settlements

While history shows that human societies tend to gravitate to this dominance hierarchy trap, it also shows that especially at the beginning these hierarchies were quite fragile. It took thousands of years from the first settlements until the majority of humans stopped being hunter-gatherers. This means for quite a long time farmers and hunter-gatherers lived in parallel. If they had the choice people tended to remain hunter-gatherers as this gave them agency over their life and when the times were good, a much more comfortable life. Also, this co-existence of lifestyle opened up a way to avoid dominance based hierarchies. If you lived in a settlement that became too hierarchical for your taste, you simply left.

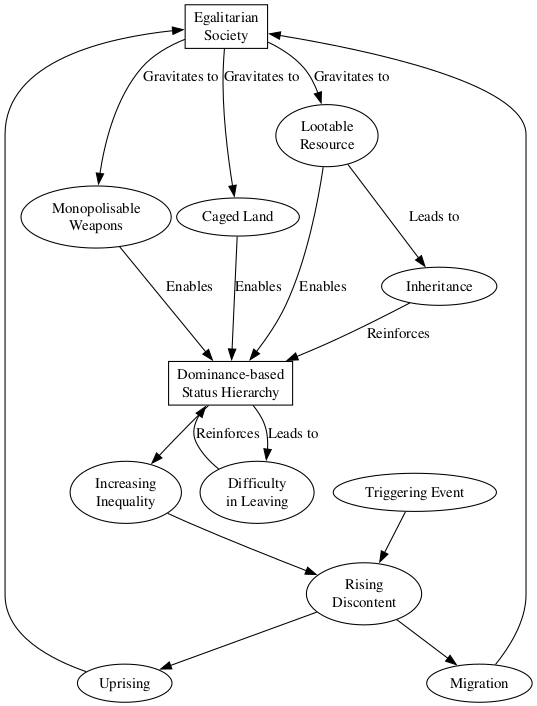

In contrast to this peaceful rejection of hierarchy, many early settlements also show a violent rejection of hierarchy. However, others also seemed to empty in a slow, peaceful trickle of people leaving. Kemp relies here on a lot of examples, but the pattern is always the same. A lootable resource leads to the founding of a settlement. This settlement is egalitarian at first, but over time we see more and more evidence of hierarchy (e.g. temples, bigger homes for some), but only up to a point. Once the inequality becomes too steep, people rise up in rebellion and kill their oppressors, or ‘vote with their feet’ and abandon the settlement. This usually is triggered by an external shock like a drought. Sometimes this does not lead to an abandonment of the settlement, but instead to a time of prosperous, yet egalitarian growth. However, in many cases after some time hierarchy creeps back in and the cycle starts anew. What is striking is the universality of the pattern. We can find it all around the globe, be it the Americas, Europe, or Asia. What we also see is that more egalitarian societies tended to survive for longer, implying an inherent instability of dominance hierarchies.

Figure 2: The boom and bust cycle of dominance hierarchies in early human societies.

We can see both in the egalitarian and the dominance based society that they developed tools and myths that entrench their current style of being. One of the main things here is religion, which is especially helpful for dominance hierarchies. You can use religion to defer to a higher power and develop stories like a monarch being essential for a good harvest. Once this hierarchy is toppled, people tend to emphasize decentralization in all facets of their life. The more decentralized you are, the more difficult it is to be dominated.

The structure of early states

Over time agricultural societies came to outcompete hunter-gatherers due to their ability to face food crises better, maintain higher population numbers, coordinate on bigger scales and actively focussed on expansion and military expansion. This meant that Goliath could grow bigger, because now wherever they extended to, more lootable resources were present, as people had already shifted to agriculture. But there were additional factors that allowed Goliath to grow bigger. Bronze enabled the creation of better weapons, domesticated animals and crops made looting resources easier, and higher population densities made dominating a territory more lucrative. All of this can clearly be seen in the data from the Seshat database (1). The best predictors for more hierarchy in a region are its agricultural productivity and the adoption of military innovations.

These shifts enabled dominance hierarchies on a larger scale. While up until then the most you could dominate was a settlement or two, now you could dominate whole regions. These new and large extractive violent dominance based hierarchies are what we now call the first states. Especially in Egypt, all these factors came together just right and allowed it to grow into the first major state.

To get back to Hobbes, we see that the opposite of his social contract happened. States did not bring order to barbarians, but instead early states created systems that extracted resources from farmers, which got little in return and could have easily lived without these states. If we compare this to today, the most similar organizations are actually those of organized crime like the Mafia. Once you have established this crime-like structure of a state, slavery is the next logical step, as it allows you the ultimate exploitation of another human (though you obviously can also have slavery without states).

Another factor that allowed these early states is linked to how people react to perceived threats. If you live in a dominance based state, you are aware that there are other states out there, which might attack you. This makes people more open to authoritarianism, as it promises more safety and people tend to become more authoritarian if they are threatened. The early states were all shaped by similar forces. Each of these states had some form of authoritative hierarchy (political power), enforced by force (violent power), supported by rituals and narratives that legitimized their authority (informational power), and extracted resources (economic power) from a defined population (demographic power).

An argument often made at that point is that hierarchy is needed to create great things. But this is not actually true. In many regions we can find big projects like temples or irrigations before we can find signs of hierarchy. It often is the other way around. Egalitarian groups build something worthwhile, which leads others to take interest in it and build a dominance hierarchy to control it.

Another important point to note here, we find in the archeological evidence that the most bloody and deadly phase of these early states was not their collapse, but their founding. Their rise coincided with conquest and war, while their collapse mostly just meant that people were free of their oppressors, at least until the next Goliath rose. The overall process of how the earliest states collapsed was quite similar to the ones in settlements, albeit on a larger scale and with more variance introduced by climate and conquest.

Collapse in early states and empires

The next logical development in human organization were empires. Essentially, empires employ the same extractive mechanism we explored for settlements and the early states, albeit at a much larger scale. You usually have a center of power that vacuums in the resources from all corners of the empire, like Rome in the Roman Empire. They are large scale dominance hierarchies. For the majority of the population living in them, they usually decreased their living standards and led to higher inequality.

While their overall dominance based structure is quite similar to early settlements and states, the way collapsed started to shift here. While early settlements and some of the early states faced rebellions which reverted them to a more egalitarian structure, we see less and less of these occurring the larger and more powerful the states and then empires became. They still tended to crumble regularly, but it was less due to egalitarian rebellions, but more due to external factors.

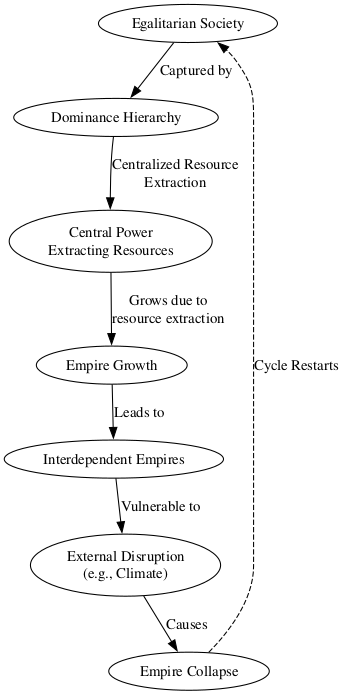

If we look at the first batch of empires that all arose at a similar time during the early Bronze Age (think Akkadian Empire or the Old Egypt Kingdom), they likely were toppled by a megadrought (called the 4.2ka event), which was a too large shock for their highly unequal societies. The drought disrupted their food production and the hierarchy collapsed, as the lack of food meant more complex states could not be supported (though regional variation on how this played out was high). It was different for the empires of the late Bronze Age (think Baylonians, Hittites, etc.). They had a more complex breakdown which we now usually call the Late Bronze Age collapse (2). This collapse included raiding sea people, a climate shift, problems with food production and other factors. But one that is very important here is that these empires relied on each other for resources like food or tin (3). Once these interconnections were disturbed, most of the empires crumbled and fell, they could not weather the impacts without this additional support.

In both cases, the late and early Bronze Age collapses, a dominance hierarchy was established which was so strong that it was more difficult to topple from within. However, it could be brought to fall by outside pressures and like with our earlier examples of collapse on smaller scales, our archeological evidence points to the fact that for most people this collapse was good actually, as their height and health improved after the collapse. They suddenly were freed from the extractive Goliath, which left them more resources for themselves and to cope with the more difficult climatic conditions. Though we can also see bloodshed and conflict here.

Figure 3: Rise and fall of empires due to external pressures.

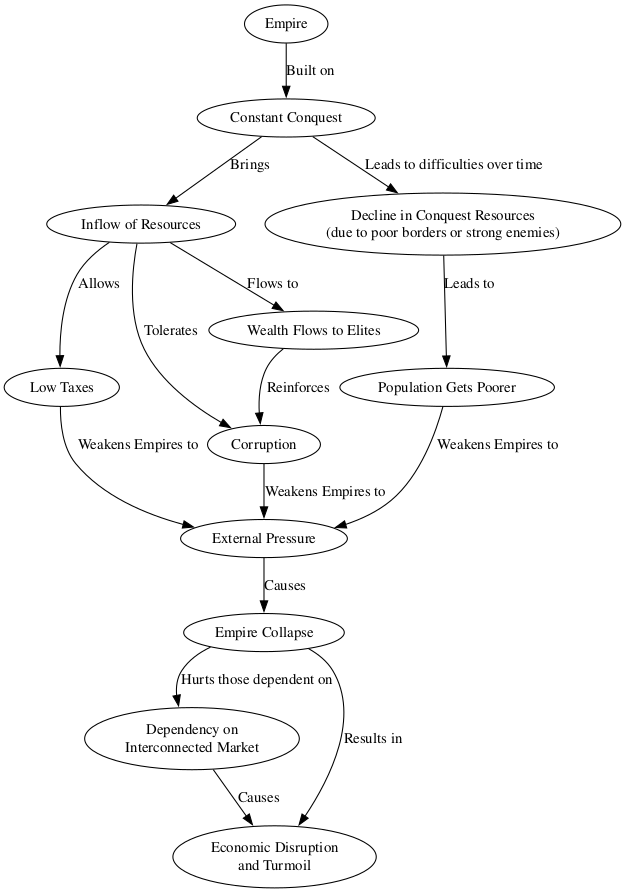

Besides this end of the empires due to external circumstances, there is also the pathway via internal pressures. However, these internal pressures weren’t the wish of the people to revert to egalitarian societies, but rather the subversive power of corruption and a system dependent on never-ending growth.

The clearest example of this way to end an empire is the Roman Empire. Rome was built on conquest. It had a strong military which was at war almost constantly. This ongoing conquest brought in lots of resources, which allowed low taxes, while also being able to tolerate high corruption. But these resources flowed predominantly to the elites. This was stable as long as the conquests kept going and everybody was better off than before. However, over time new conquests became more difficult. Many of the regions that Rome bordered to later on were poor (e.g. the Germanic tribes) or so powerful they could not be conquered (e.g. Sasanian Empire). This meant the constant inflow of resources by conquest stopped. While the elites could still acquire more and more resources by corruption and dominance, the general population got poorer. Also this was over accompanied by overworking the resources of the land. The decrease in resources led to factionalized elites. All this left the empire in such a weakened state that it could not resist outside pressure anymore and collapsed. However, this collapse was quite bad for a vast part of the population, especially the ones that had been part of the empire for hundreds of years, as they had become dependent on a large interconnected market of specialized production. When this vanished, many regions had to completely re-order how and what they produced.

Figure 4: Collapse of conquest dependent empires.

This pattern was not unique to the Roman Empire, but could be found in many of the empires of antiquity. An especially interesting case here is China. It suffered from similar problems as Rome, but it lasted for longer. This longer time frame also gives some more interesting data to look at when it comes to how extractive the Chinese empire was. We can find a clear correlation between how extractive the state was and how long the individual emperors lasted. The less extractive their policies were, the longer they remained on the throne. However, this also leads to the problem that a less extractive empire is often a weaker empire, as it cannot maintain larger armies. This in turn makes it more vulnerable to conquest. This is the reason why so many of the states throughout human history have relied on dominance hierarchies. Dominance hierarchies make it easier to defend yourself, as you can more easily mobilize manpower and violence. While an egalitarian society makes life better for those living in it, it also makes them potentially more vulnerable against the dominance hierarchies around them.

What we can also see when we look at collapsing empires is that different parts of them collapsed on different timeframes and especially their general culture never really collapsed, but just transitioned to a new system. Political collapse was often rapid, occurring within years or decades. Economic breakdowns typically followed within a century. However, shifts in information systems and population dynamics unfolded over several centuries. Some aspects remained unaffected entirely.

We can also see that there is a clear underlying pattern. Empires collapsed when their internal inequality became so high that it decreased their resilience. Once their resilience was low, they were toppled by the next catastrophe that came along and it did not really matter if it was climate, war or something else.

Collapse, colonialism and capitalism

As we have seen so far, the reach of Goliath increases in step with the capabilities of humans. When we were early farmers Goliath could be as big as a settlement, it then grew to early states, then to continent spanning empires. The next step were the colonial empires which spanned the whole globe. The colonial conquest of empires like the Spanish or British relied strongly on their improved technology, but also on weakening other empires via disease and fueling internal disagreements. This global conquest was arguably one of the most brutal things humanity has ever done. It is estimated that in the Americas, Australia and Hawaii up to 90 % of the population died and this population stayed low for centuries because they were so violently oppressed. The disruption was so strong that it even touched upon regions that were never colonized directly, but that were still wrecked by imported diseases and political instability. Interestingly, this birth of the global Goliath is seldom counted as collapse, because from a European perspective it led to growth and urbanization, even though the cost was the extinction of whole cultures. Maybe we should be much more cautious about the beginning of empires and not their end. If we look at history, the rise is pretty much always much more brutal than the end.

At the same time we can see the beginnings of capitalism. Capitalism and colonialism were a good match for each other. Capitalism relied on growth and extracting resources, while colonialism allowed access to a large amount of resources on the cheap. It also ushered in a new form of inequality that had not existed before. Early capitalism was advantageous for very few people. Even in the heartlands of empires the majority suffered under horrible living conditions. For example, even though England was clearly the single country which profited most from colonialism and early capitalism, life expectancy fell by almost 20 years and the height of adult men by almost 10 cm.

Thankfully, the majority of horrors of colonialism only lasted for around 100-200 years. Since then the world has largely (at least formally) decolonized and living conditions have improved again worldwide. However, this time brought with it a lasting change. Arguably, since then no state has collapsed in a lasting fashion. Sure, countries have gained and lost territories and from time to time some nations become failed states, but none collapsed like the states and empires in earlier history. We have clear transitions of powers, albeit sometimes violent ones. Even failed states still have some access to global markets and they usually stay “failed” only for a few years, before a new government forms.

So, is our modern system the end of collapse? Have we slain Goliath? Not really. We still have empires (e.g. Russia, China or the United States), we just have stopped calling them that way. Many of our modern institutions are still dominance based hierarchies, created and maintained to extract resources. What actually happened is that the product of colonialism and the conflicts of the 20th century created a global Goliath, which contains every nation on this planet. This Goliath is self-stabilizing. If states struggle, other states stabilize it again, as this is often an opportunity to make money. We have seen in many failed and struggling states that a big wave of privatization occurred, after which they were part of the global economy again. But there are other reasons as well that make the collapse of dominance based extractive systems much less likely now. Modern weapons make it much more difficult to resist, but what is likely the strongest reason: We take dominance based hierarchies for granted, because humanity has lived under their control for thousands of years now. This does not mean collapse is impossible now. It just means it has to be a shock that hits the whole global system at once.

A general theory of collapse

Before we dive into what these global shocks might be, let’s recap a bit the main patterns we can see from all these historical ideas and examples. Much of this is related to inequality. More equal and inclusive societies tend to weather shocks much better. Also, more unequal societies tend to suffer more from a variety of problems which make them less well equipped to react to crises. Wealth gives you power. The more wealth you have, the more you can shape society to be more like your preferences and the personal preferences of a single person seldom overlaps with which would be best for a society as whole. Wealth inequality is self-reinforcing. In our modern societies the wealth you gain from having capital is much bigger than the wealth you gain from labor. Therefore, the rich tend to get richer, which in turn increases their undue influence on society. This further gets entrenched via debt. If I owe someone money, it gets much more difficult to resist them, as they have an additional power over me. But also via rich people buying things like media companies or lobbying teams to influence politics. Power begets power.

Besides these direct negative consequences, inequality also leads to a variety of follow-up problems. Inequality leads to unequal power which leads to corruption. The greater the discrepancy in power, the more opportunities arise to exploit this power. Corruption decreases trust in the state and in other people, removing the glue that holds society together. Inequality also makes oligarchy easier. If you have more wealth and power, it gets easier to carve out a part of society that you tightly control. As wealth inequality grows, more elites compete for high-status positions. Aristocrats, lawyers, nobles, and generals—those with resources—either organize rebellions or take over existing ones. This rise in elite competition is central to structural-demographic theory, a model first developed by Jack Goldstone and refined by Peter Turchin (4). It just seems that inequality is inherently corrosive to every society.

In addition, to these factors which are very directly related to inequality, there are also two other factors that come into play:

Imperial Overstretch: Empires like Rome, the Qin, and the Mongols believed their rule was divinely ordained and should be universal. The British and other colonizers saw themselves as civilizing savages, while Islamic rulers expanded the umma. Conquest offered legitimacy and practical benefits: neutralizing threats, securing resources, and rewarding elites with land and plunder. However, expanding borders often created new enemies and increased costs, leading to “imperial overstretch.”

Declining Energy Ratio: Societies depend on energy, and the ratio of energy expended to energy gained, called “Energy Return on Investment” (EROI), is crucial. Many civilizations, like the Western Roman Empire, faced declining energy ratios due to dwindling resources and environmental degradation. However, a poor energy ratio alone rarely causes collapse—it contributes, but other factors are typically involved.

These problems are interconnected. Resource extraction, whether from people or nature, faces diminishing returns. The severity depends on a society’s resilience and its ability to adapt. Larger empires with advanced technology and control systems can expand further and are less prone to rapid collapse. However, extractive institutions and inequality breed oligarchy, corruption, and elite competition. As these factors interact, they worsen each other—corruption fuels inequality, and oligarchy leads to poor environmental management. The state becomes fragmented, with elites draining resources, gradually hollowing it out.

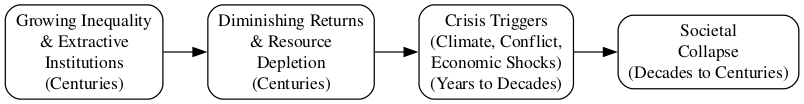

Taking all this together, Kemp formulates a general four step process of collapse (Figure 5). Extractive institutions lead to inequality. This in turn leads to weakening processes like corruption. Once the society is weakened enough, it essentially just waits for a trigger to start the process of collapse.

Figure 5: The four steps to collapse.

What makes societies resilient against collapse

There are some universal principles, such as knowledge storage and creation, which large states and empires excel at. For instance, historical empires often stored and passed on technological advances, contributing to long-term resilience. Similarly, strong religious or ideological unity, and the ability to reform and decentralize (as seen in the Byzantine Empire) also help reduce intra-elite competition, which makes societies more resilient.

However, there’s a strong argument that more inclusive and democratic systems are an even more important factor during crises. Studies by Peter Peregrine (5) show that societies with greater political inclusivity and collaboration tend to be more adaptable to catastrophes like climate change or disease outbreaks. Modern democracies are often more resilient in part because they allow diverse viewpoints to shape decisions, leading to more comprehensive solutions during disasters (6). Citizens’ assemblies, which have proven successful in addressing polarized issues, exemplify this. Also, there are many other examples where the collective wisdom of crowds works pretty well: forecasting, foresight, collective intelligence. Distributed information processing seems to result in better decisions. Also, this decreases the influence of people high in the dark triad and the corrupting influence of power.

Yet, many modern democracies are still indirect in how they channel citizen input, limiting their potential. A more direct application of participatory decision-making could improve resilience even further.

But resilience is a double-edged sword: a system can be resilient even when it’s a bad one. This makes democracy crucial because it not only fosters resilience but also has the best chance of creating a good system that’s worth sustaining. Interestingly, societal collapse often was a path to enable more inclusive government. In many historical examples, collapse led to less dominance hierarchy and more egalitarian societies afterwards. So, in some way societal collapse could be seen as a cultural adaptation to too high inequality and too little inclusivity. Also, as we discussed earlier, debt is an important mechanism to enforce dominance hierarchies, but if your society collapses, this also usually erases all debt and provides the following societies a clean slate on which they can start again.

Modern day collapse

Historically, it looks like societal collapse is less of a problem than you might think. When we look at history, the most brutal and horrible events almost exclusively happened when a new Goliath rises (e.g. the rise of the Mongol Empire or the conquest of the Americas). When groups of humans try to rise to the stop in their own society they often use violence. When they succeed and start conquering their neighbors with their newfound power, it usually gets even more brutal. However, on the other side of the arc of history, in societal collapse we seldom see brutality at that scale. Instead, we see societies that erase their debts, level hierarchies and decentralize, so they can live more egalitarian again.

Does this mean that even today a societal collapse would possibly be an event that makes things better instead of worse? Unfortunately, the answer is probably no. On the contrary, it seems like we have built ourselves a trap. While the global Goliath continues to lead to extractive dominance hierarchies, it has also led to a rise of new technology. Technology that would make any potential conflict, might it be caused by collapse or otherwise, much more deadly. This includes things like nuclear weapons, but also gain of function research, AI or industry loss via an electromagnetic pulse.

Besides these tools and processes which make the breakdown of international order a collapse would likely imply more dangerous, we also have made the planet itself much more vulnerable and inhospitable due to climate change and overstepped planetary boundaries.

The final problem is that we created a global system which is highly interdependent. There is no easy going back to lower levels of complexity. Even ignoring the problem that everything in our system is aimed at evermore growth, economic complexity is not something you can easily dial back, if it gets too difficult to maintain. Instead, we have a network of networks. If one part of these networks fail, it seems likely that it will bring the whole system crashing down. This system is pretty resilient against smaller shocks, but as the global Goliath works towards more inequality and more inequality makes us less resilient, it looks like we are steering towards a world that will get less and less resilient until we get unlucky and a hazard happens that is larger than our diminished resilience. Modern supply chains optimize for efficiency over resilience. Just-in-time delivery means factories often have less than a month’s supply of critical components. For example, during the 2011 Thailand floods, these factors caused factory closures across multiple continents, as stocks of things like hard drives quickly depleted.

Besides the obvious reason that this collapse would be bad, we should also avoid it because chances are that over time it could lead to the rise of a new global Goliath. As we have seen this rise was probably the most violent thing ever done in human history. We should make sure to not repeat this.

What to do?

We live in paradoxical times. While the last section might sound all doomy, it is only half of the story of our times. Yes, we have built ourselves a trap and when it would snap, we would all have a pretty bad time. However, modern humanity is also better equipped to handle danger than ever before. We have the science to understand what is going on, there are ideas out there on how we could solve it. We “just” have to do it. This might even be easier than we generally think, because if you boil it down, there are very few key players that have to change. These are exactly the ones you would guess. Two nations control almost all nuclear weapons, the vast majority of climate damage is done by very few companies, only very few companies have the capability to even have the chance to create general AI or mass surveillance which is also implemented by a handful of key companies. These agents of doom are usually dominance hierarchies themselves, which push them towards making decisions that only favor their growth and continuation and nothing else.

When we summarize the arguments made in Kemp’s book, one thing that becomes pretty clear is that humans like to live in egalitarian and free societies. Paradoxically, societal collapse in the past has been a way to get back to more egalitarian and free societies. But this came at a cost. We lost technological progress, many people lost their lives. So, if this is the case: why don’t we cut out the middleman? If more egalitarian and free societies are the upside that collapse brought us, we could also get there without the downsides.

When wealth inequality and centralized power is the root of all evil, we can redistribute wealth and we can break up power monopolies. Even today the idea of universal basic income and other ideas along those lines get a bit more popular every day. If democracies lead to more resilient societies, we can strengthen them today. Citizens’ assemblies have a good track record of doing exactly that and they get used more and more often. But we need this democratic push not only in governments. We need it on all levels of society. Because if we don’t democratize the few institutions and governments that have brought us into this situation, it will be difficult to get out.

Or to say it differently, let’s build a future where we have an egalitarian and equal society that decides in consent what brings the most health, happiness and general welfare for everyone.

Let’s bring an end to dominance hierarchies!

How to cite

Jehn, F. U. (2025, August 6). The people’s history of collapse. Existential Crunch. https://doi.org/10.59350/3qg73-sxp76

Endnotes

(1) A vast historical dataset, which we have already mentioned a bunch of times on this blog: 1, 2, 3, 4

(2) We discussed this collapse more in an other post.

(3) We discussed the consequences of such trade collapse in an other post.

(4) I explain this theory here.

(5) We discussed those studies here.

(6) For more explanations on why democracies increase resilience, see here.