When we talk about societal collapse, we usually talk about the factors that led to the collapse of a given civilization. However, you could also turn this around and ask what factors allow civilizations to avoid societal collapse and major crises. Knowing more about this would be quite valuable, because generally, you would rather avoid major crises, instead of having to try to solve them once they started.

Under what conditions are long-term risks tackled before they become a crisis?

Exactly this kind of question is tackled in a review by Shwom and Kopp (2019). They are motivated by climate change, as they see this as the main long-term risk we face right now, but the results they find are generalizable. This one is especially interesting, as they try to tackle this question from an as wide angle as possible and include insights from a lot of different fields. They structure their review along several questions:

What risk perceptions would make action on long-term risk more likely?

They start with a focus on psychology. From their findings they argue that the main reason from a risk perception standpoint is that people have more psychological distance the more long term risks are. This mostly means if something feels more or less directly relevant for your life. The psychological distance increases if an event is farther away in the future and if its outcomes seem more uncertain and ambiguous. While we cannot change how far something is in the future, we can change how uncertain or ambiguous something feels. Shwom and Kopp highlight the value of fiction here, especially if it is concerned with the suffering of future people and invites the people interacting with it to take the perspective of the future harmed people. But also other things like sharing experiences related to the risk in group discussions seem to make it more concrete for people (1). When the risk becomes more concrete, it tends to trigger a reaction of fear and anxiety and these negative emotions are then often the driver to move people to act in precaution of the risk.

When will societies weigh the costs and benefits of long-term risk as action worthy?

In the answer to this question Shwom and Kopp focus on expected utility theory. With this they mean assessing if the cost of acting against the risk now is higher or lower than the future damages of the risk, discounted by how far they are in the future and how likely they are. Calculations like this are done by many institutions in the form of cost benefit analysis. In analysis of many past cost benefit analysis, it has become apparent that most institutions heavily discount the future and thus are biased against action against long-term risk. Interestingly, this seems to be different for individual humans. Shwom and Kopp cite here several studies that gave people the option to assign value to environmental crises across different time horizons and found that around 30-50 % of their respondents don’t do time discounting at all (2). This means if an environmental risk is 5,10 or a 100 years away does not matter to them, they want us to avoid it all. Unfortunately, it seems that these studies don’t offer any good answers on what makes a large chunk of the population not have future discount rates for environmental crises. But a good way forward here might be to assess the discrepancy between what individual people want and what institutions (which consist of these people) want.

What social, cultural and institutional factors would predict that society will act to address long-term risks?

The first two questions showed that people differ in their assessment of long term risk and can be moved to care more about it. However, societal reaction is still lacking, so there must be other factors at play. Based on their review Shwom and Kopp think that the missing piece here is how society processes information. Obviously, what kind of and how you get information is shaped by the way your society is structured. But what the research here seems to be showing is that to get action going to tackle a long-term risk, there is some kind of focussing event needed. These are often disasters that relate to the long-term risk. Such events allow the society to clearly identify the problem and the suffering inflicted provides the motivation to change things. However, for this to be really successful, the crisis needs to be socially amplified. This means you have to have a critical mass of experts and media people interested in the topic before it happens and once the focussing event happens they are able to amplify the topic into the general discourse of the society. This process can be distorted by bad actors which withhold information or produce disinformation. So, you have to keep those in check if you want your social amplification to work. One thing that helps is to emphasize the existing scientific consensus, as there is research showing that people tend to be more open to act on a risk in general, if they know about it and have the impression that the scientists are all pointing in the same direction.

Summing this up

My main takeaways from Shwom and Kopp are that you have to inform people about the long-term risk, work on making it more concrete for them by working with fiction and highlighting the scientific consensus. In parallel you have to work on getting experts and people in the media interested in the topic in general. Then you have to wait for a focussing event and use this to amplify your message around the risk and force society into action.

However, Shwom and Kopp also emphasize in their review that these are very preliminary results and there is surprisingly little research around long-term risk governance in general. In addition, this research is spread throughout many disciplines, which often do not know what the other fields are doing. So, we need a lot more research here and especially empirical one.

Quantitative history to the rescue

This is the part where everyone’s favorite quantitative historical database Seshat comes into play. A recent article by Hoyer et al. (2024) tries to make a first exploration of how averted crises play out using this data. However, this is quite a tricky thing to look at. By definition, averted crises cannot easily leave a big mark in history, because they did not happen. To be able to detect an averted crises they lean on structural demographic theory. We discussed this briefly in the first post in this series, but here’s a quick refresher.

In structural demographic theory the idea is that your society goes through a cycle of increasing pressure, which gets released at some point and then the cycle starts anew. This goes through several steps:

- Your society is growing, there are enough resources for everyone, everything is quite stable.

- Your growth starts to slow down, because you hit some limits (e.g. there is no more territory to conquer). Elites start to amass more and more of the remaining wealth and the general populace starts to get poorer.

- As the elite’s number keeps growing at the cost of everybody else, they too run into limits, as there are only so many prestigious positions to go around. This leads to competition within the elites.

- The state starts to run out of resources, as the high number of competing elites takes an ever greater share of the available wealth for themselves.

- The pressure of a poor and unhappy general populace, infighting elites, and fiscally stressed states results in a disruption which resolves the pressure. This can be anything from major reform to a civil war.

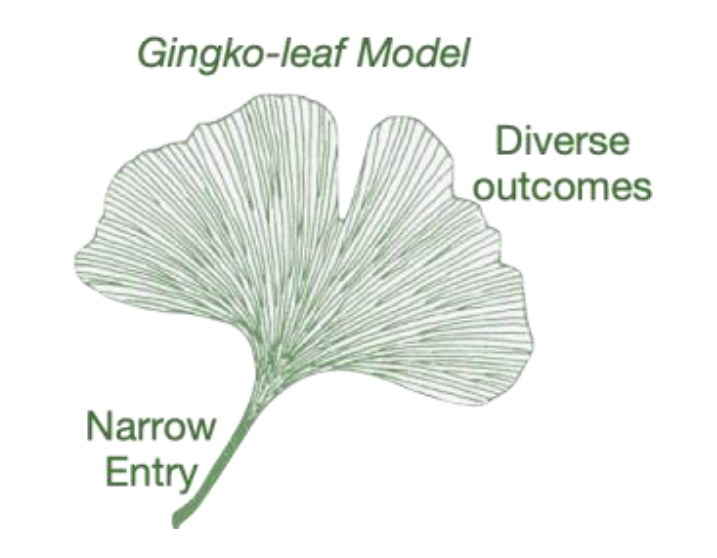

This means that there is a similar process in the build up of stress for all societies, but the important question is how and at what stage this pressure is relieved? Hoyer and co-authors here use the analogy of a Ginkgo leaf. There is one fairly common path to crises, but many ways to exit (3).

Figure 1: How a crisis plays out similar to a Gingko leaf.

The key indicators to understand where in the cycle you are is popular immiseration, elite overproduction, intra-elite competition and fiscal distress. These are all things you can measure (or at least proxies of them). Therefore, to find cases of averted crises you have to measure these indicators and find historical events where they were very high, but the pressure was relieved in a productive way, which did not result in destructive events like civil wars.

This is exactly what Hoyer et al. did, and they found four events where you have a big pressure build up, but no immediate crisis, but instead a release of pressure (4).

The case studies

Conflict of the Orders in the early Roman Republic (494-287 BCE)

The early Roman Republic was quite an achievement, because it managed to move away from monarchy to a republic. While this led to some redistribution of wealth and political power, it still meant that most of the power was held by a small number of aristocrats and the general populace (the plebs) did not have much say. These differences between the aristocrats and the plebs increased over time, as the aristocrats amassed ever more land and small holder farmers were pushed to the margins. Also, the early Roman Republic was almost permanently at war. This led to a massive influx of wealth, which was mainly funneled to the aristocrats. Therefore, Rome had popular immiseration, elite competition around the relatively small amount of public offices, but little fiscal stress. These highly unequal circumstances led the plebs to essentially go on strike and demand both political power and a more equally shared wealth. Such strikes happened several times and allowed the plebs a larger share in the societal wealth, while also giving them institutionalized legislative authority. Once this was in place, the pressure was relieved and the crisis was averted.

Rome was probably successful here, because the elites were willing to do a reform. This willingness was likely due to the constant warfare. The elites were reliant on the plebs for their armies. If no agreement was reached, Rome risked conquest by neighboring states. Also, the conquests of other territories made it easier to reform, as the additional wealth made redistribution of wealth less of a hot topic, as there were enough spoils of war, that the elites were open to share some of that without really losing most of their wealth and privileges

Chartist movement in England (1819-1867)

The United Kingdom grew a lot in the 17th to 19th century and acquired a large number of colonies. The exploitation of those colonies meant a steady influx of wealth to England, which contributed to early industrialization, which in turn accelerated economic growth as well. However, the spoils of this quickly growing empire were distributed very unequal. Most people had next to nothing and many of the jobs in industry were quite hazardous as almost no regulation existed. Also, there was no universal suffrage, so most people did not even have political influence to try to improve their lot. This resulted in growing unrest and societal stress in the 19th century. From the structural demographic theory indicators the popular immiseration shows up most clearly. Real wages had been declining since 1750. There was potentially an elite overproduction, because university admissions rose sharply. Fiscal stress however was not really present, as the empire was flush with wealth from its colonies. As in the example of the Roman Republic, the pressure was relieved via reforms. This happened in several steps, as the first attempts at resolution were not far reaching enough or did not get enough buy-in from power-holders. These reforms increased welfare considerably (5), introduced more laws around labor and created universal suffrage. These laws could only be passed after there had been massive strikes and rebellions, as before that the elites were not open enough for a compromise that would cut into their profits and status. But still it is a remarkable outcome, as in most of such cases labour unrest is simply suppressed.

As with the Roman Republic, England could reform more easily because it imported wealth and resources from its colonies (though this clearly harmed people living in these colonies). England was also able to relieve population pressure through emigration, making domestic reforms easier to implement.

Reform period in the Russian Empire (1855-1881)

Over the course of the 18th century the Russian Empire had expanded a lot. This had led to an influx of wealth to the central parts of the empire at the cost of the periphery. Overall, the economy had been growing quickly, but the population grew even quicker, meaning the real wages were declining. Also, the societal structure in Russia still allowed serfdom, which meant that most farmers were tied to the land they worked on and not that far from being slaves. This was in sharp contrast to the liberal ideas from Enlightenment thinkers, which were making the rounds in Europe at the time. This made the general population very dissatisfied with their situation. The elites on the other hand had profited considerably, as they had been able to carve out a lot of privileges. They also did not have that much intra-elite competition, as they were united against the states that aimed at curtailing these privileges. All of this was combined with empty state coffers, due the many wars that were fought by Russia in the 19th century. When Alexander II came to power, he aimed for wide ranging reforms, to stabilize the situation. He led reforms to free the serfs, modernize education and judiciary. However, these reforms went strongly against the interests of the elites and as there had been assassinations and coups in the past. This led to Alexander II becoming cautious, which in turn made the reforms less ambitious.

These toned down reforms resulted in only partial success. The reforms brought some peace because peasants had some demands met, but wealth inequality remained largely unaddressed. For many freed serfs, “freedom” mainly meant paying the same amounts to the state that they previously paid to aristocrats. This left many grievances unresolved, which temporarily pacified the country for some decades but ultimately led to revolution in 1917. Unlike the fully successful cases, Russia failed to achieve sufficient elite buy-in for sufficient redistribution of wealth and power.

Progressive Era in the USA (1914-1939)

The American Civil War was fought around the issues of slavery, states’ rights and economic and cultural differences. While it resulted in slavery being abolished, it was not able to resolve many of the systemic issues in the United States. There was still systemic racism, the rapid industrialization disrupted the society and the central government tried to reassert its central authority. These factors lingered or grew throughout the 19th century. At the same time the country grew massively, both in territory and economic size. As in England, this often came together with hazardous working conditions for many and few rights to protect you. Also, much of the wealth was funneled to a small group of elites, who grew over time and started to fight over political influence. Fiscally, the state was in a somewhat neutral position, it did not have much debt, but the overall state structure was rather small and inflexible, with little reliable income streams. All of this meant that you had a massive amount of pressure building up.

This was partially relieved by the First World War, which focussed much of the public attention away from social issues. However, there had also been a positive trend even before the war. In the first decade of the 20th century, labour laws were strengthened and unions started to grow considerably. Even some of the major industrialists started to advocate for reform and introduced better working conditions in their factories. These trends were reinforced by the Great Depression. The economic collapse demonstrated that further major systemic changes were necessary to restore peace and prosperity. This crisis ultimately prompted Roosevelt’s New Deal reforms, which raised general welfare and reduced instability across society by redistributing wealth and creating stronger safeguards against economic hardship.

Main factors

The case studies reveal several patterns in successful crisis aversion. First, expanding territory and economic growth help maintain social peace by allowing greater wealth distribution without requiring elites to surrender existing assets. This often coincides with increased national unity when facing external threats.

Second, even after significant social pressure builds, resolution through reform remains possible. The challenge is pushing reforms far enough against elite resistance and managing to forge a broad societal alliance that has enough power to maintain the momentum of the reform projects. Without sufficient reform depth or a too small coalition, as in the Russian Empire case, you only get temporary relief rather than lasting stability.

A consistent theme across these cases is that when a small elite group amasses a large portion of society’s wealth, it leads to hardship for the majority. Peace was only reestablished when wealth became more equally distributed and democratic participation expanded to include more of the population.

The critical element in all successful cases was securing enough elite buy-in and a broad enough societal alliance to implement meaningful reforms. This societal alliance can be made of state power holders, elite factions or other interest groups. They have to be strong enough to assert authority over the special interests of powerful elites while having the legitimacy to implement changes.

Also, it seems that the conditions have to get “sufficiently bad” to allow reform. In many of these situations, reform would have been possible much earlier than it was actually implemented, but there was not enough pressure in the system, to highlight to the elites that they had to tolerate that their privileges would be partially dismantled.

Takeaway

Obviously, we have to take this study with a grain of salt, as it is only four case studies and these always have the potential to be cherry picked. Hopefully, the Seshat team will publish a follow up with a bigger dataset, so we can be more sure of the results here.

However, all these insights align quite well with many other topics that we have discussed on this blog. For example, that inequality seems to be an important factor for societal collapse in general, that forging a broad societal alliance and having elite buy-in is important if you want to do reform or that making your society more democratic seems to be a promising way to make it also more resilient against crises.

Therefore, I am hopeful that follow-up studies using larger datasets will confirm these conclusions, though we must wait for their publication before drawing definitive lessons for contemporary crisis prevention.

Endnotes

(1) Another example here are the storylines we explored in an earlier post.

(2) Problem with these kind of studies is that for the participants nothing is really on the line, so we cannot be sure if they really behave like this in their everyday life.

(3) If you want to learn more about this, the CrisisDB team also has another big study about the database, which I have discussed here.

(4) This does not mean that there are only four cases in history, these are just some of the most striking ones they singled out as case studies.

(5) Though only if you were a white male living in England. Everybody else still had a bad time.

How to cite

Jehn, F. U. (2025, May 21). Reform or ruin. Existential Crunch. https://doi.org/10.59350/phqtd-z9p60

References

- Hoyer, D., Bennett, J. S., Whitehouse, H., François, P., Feeney, K., Levine, J., Reddish, J., Davis, D., & Turchin, P. (2024). CRISES AVERTED How A Few Past Societies Found Adaptive Reforms in the Face of Structural- Demographic Crises. OSF. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/hyj48

- Shwom, R., & and Kopp, R. E. (2019). Long-term risk governance: When do societies act before crisis? Journal of Risk Research, 22(11), 1374–1390. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2018.1476900