Electricity is essential for the functioning of our modern society, as nearly everything we do depends on the electrical grid in some way. While this reliance provides significant comfort and convenience, it also makes us vulnerable if the grid fails. But what happens when the grid stops working? This question is thoroughly explored in the book Was bei einem Blackout geschieht: Folgen eines langandauernden und großräumigen Stromausfalls (What Happens During a Blackout: Consequences of a Long-Lasting and Large-Scale Power Outage) by Petermann et al. (2011). I highlight this book because it offers the most comprehensive analysis I’ve found on the societal impact of losing all electricity-dependent systems.

Importantly, this book is not just another academic publication. It was produced by the Institute for Technology Assessment and Systems Analysis (ITAS) following a mandate from the German government to investigate the consequences of blackouts in Germany. In addition, as the book is in German, and many of my readers are English speakers, I believe it’s particularly valuable to discuss it here, as most of you likely aren’t aware of it.

The book’s findings are based on expert interviews and a methodical examination of the potential consequences. While there was no modeling involved—a limitation acknowledged by the authors due to budget constraints—the conclusions are logical and straightforward. The book is organized by the different sectors of society that would be affected by a blackout, including general effects, communications, transportation, water and food systems, healthcare, finance, as well as potential solutions to mitigate the impact.

General situation

For a prolonged major blackout to occur, it would likely require the physical destruction of critical components in multiple power plants or within the transmission network—components that are difficult to replace. These could be caused by a variety of factors. Peterman et al mention technical and human failures, criminal or terrorist actions, epidemics and pandemics, and extreme weather events (1). The likelihood of such blackouts might increase in the future, largely due to the growing risks posed by terrorism and climate-related extreme weather.

In the event of a prolonged blackout, the supply of essential goods and services would quickly become challenging, putting public safety at risk. The state might struggle to meet its obligation to protect its citizens, even with the full mobilization of available resources.

Germany faces some additional challenges due to the structure of its critical infrastructure, with approximately 80% being privately owned (consisting of a large number of small companies), which makes coordination more difficult. Furthermore, the responsibility for managing blackout risks is divided among various institutions. Initially, local authorities handle the response, but as the situation escalates, higher levels of government are drawn in. Effective crisis management would require coordination across multiple levels—local, regional, and national. However, Germany’s federal system complicates this process, as leadership and coordination are not uniformly executed across different levels of government. Also, the coordination required here is neither trained nor planned for.

Moreover, the public’s lack of awareness and preparation for such an event adds to the challenge. Many people associate disasters like power outages with unavoidable natural events or terrorism, leading to a sense of fatalism and a lack of personal preparedness. To address this, it is important to increase public awareness and encourage preparedness, so that in the event of a crisis, effective communication and response can be achieved.

Communication

In the event of a major power outage, communication systems would be among the first to fail. The complex structure of information and telecommunications networks is heavily dependent on external power sources. Landline phones would stop working immediately or in a few hours (depending on local back-up power). Mobile networks, while initially functional due to battery-powered devices, would quickly become overwhelmed by increased usage and would soon fail as their base stations lose power. Radio broadcasts are expected to function the longest, while internal government communication networks might also remain operational for a few days due to their backup power supplies (2). However, the internal government measures would only be available for a minority of people. In the event of a blackout, communication with the population would be severely hampered. While there are ideas for maintaining communication, such as using radio stations with emergency power or setting up local information distribution points, these are temporary solutions with limited capacity.

The loss of communication would have profound effects on other sectors. Unlike healthcare, water supply, or transportation, which can partially operate without electricity, communication technologies rely entirely on a stable power supply. Without electricity, telecommunication and information processing would cease entirely, severely limiting the ability to coordinate responses or communicate with the public.

The vulnerability of the communication infrastructure is further exacerbated by the fact that the power grid and communication systems are mutually dependent. The electrical grid is highly complex and needs coordination and communication across the whole country to work reliably. A failure in one can lead to a failure in the other, creating a cascade of outages that are difficult to recover from. Restarting communication networks after a blackout would be a slow, incremental process, with full restoration likely impossible in the short term due to the complexity and scale of the networks (e.g. all batteries are drained and you don’t have enough power in the system to charge them all at once and people start heating their water tanks). There are currently no comprehensive plans to make these systems more resilient, largely due to the prohibitive costs and technical limitations. Some improvements might be possible with the integration of renewable energy sources (3), but overall, the situation remains difficult.

Transportation

Transportation systems would face significant disruption. Electrically-powered modes of transport, particularly trains and subways, would come to an abrupt halt within minutes. This affects not only the vehicles themselves but also the infrastructure, control systems, and organizational aspects of these transportation networks.

Rail transport would be severely impacted, with many people potentially trapped in trains and subways. Control centers, signal boxes, and safety systems would be drastically limited in their functions, significantly hindering population mobility. Harbor operations would largely cease due to the failure of loading equipment. Airports, however, prove relatively robust and could continue functioning for days or even weeks thanks to large emergency power systems (4).

Road transport would become chaotic, especially in densely populated areas. Things like Traffic lights or tunnel lighting would fail, leading to blockades, traffic jams, and an increased number of accidents, including some with injuries and fatalities. Emergency services would struggle to perform their duties effectively, as the roads are blocked in many places.

While vehicles with fuel in their tanks could continue to run initially, the inability to refuel at non-functioning gasoline/diesel stations would quickly lead to a sharp decline in private motor vehicle use after the first 24 hours (5). Public transportation by non-electric buses may continue on a limited basis.

As a mitigation measure, some train services can be maintained using diesel locomotives. However, the stranded electrical trains would block the rails for diesel trains. Authorities, in cooperation with logistics companies and railway operators, would need to establish transportation corridors and allocate transport capacities to enable the supply of essential goods, particularly by rail. This involves deciding which routes should be kept open and what measures need to be implemented for emergency operations.

Water system

Water infrastructure faces severe challenges due to its heavy reliance on electricity. Most water systems cease functioning almost immediately when power is lost, leaving a significant portion of the population without access to fresh water (but there would be some water left in the system that could be used). This impacts all aspects of water management, from extraction and treatment to distribution.

The failure of electric pumps is particularly critical, as it prevents groundwater extraction. Water treatment plants and distribution systems become limited to gravity-fed operations, significantly reducing water availability and leaving higher elevation areas completely without supply.

Sewage systems, designed for specific water volumes, face potential blockages due to reduced water flow and changes in wastewater composition (but this would likely take some weeks or longer to become a bigger problem). In many cases, untreated sewage may need to be diverted directly into rivers, causing immediate environmental damage and contaminating local water sources. The lack of water also affects personal hygiene, increasing disease risks and complicating cooking. Furthermore, it hampers firefighting capabilities while simultaneously increasing fire risks as people resort to alternative cooking and heating methods.

To mitigate such issues, Germany has a network of 5200 emergency wells separate from the normal drinking water system. Originally created for wartime scenarios (with an attack of the Soviet Union in mind), the locations of these wells will only be disclosed to the public during major catastrophes to avoid them being tampered with. These wells have enough capacity to provide an average of 15 l of water per person and day (6). This is around a magnitude less than what is used now, but should be enough for drinking water, food preparation and basic hygiene. Areas without wells will rely on water transportation by trucks. Additionally, local emergency power can be used to operate water pumps temporarily and refill local storage. These combined measures should provide at least some drinking water for a majority of the population.

However, current assessments are largely based on theoretical considerations rather than actual models. Developing such models would help test assumptions and improve preparedness. One potential improvement is redesigning wastewater treatment plants to produce their own power using biogas, making them independent from external power sources and capable of continuous operation.

Food system

The current food supply system faces several vulnerabilities in such a scenario. A significant portion of our food supply is frozen, which would be lost within days without electricity. Additionally, modern factory farming, with its tightly controlled environments, would face severe challenges. Many animals in these facilities could perish within hours to days due to the failure of essential systems like lighting, heating, cooling, ventilation, and cleaning.

The main challenge in a blackout scenario is not necessarily the overall amount of food available, but rather the logistics of distributing it to where it’s needed. While there are large food reserves, transportation breakdowns could prevent timely delivery to many people. Furthermore, many individuals lack the means to cook without electricity, necessitating the provision of ready-to-eat meals.

The current structure of the food distribution system makes it likely that any response will only be partially effective and highly variable across different locations. Some areas might have sufficient food supplies, while others could face severe shortages. Most retail food stores have limited storage capacity and typically rely on frequent deliveries. Without power, these stores could deplete their stocks within a few days. The food supply chain would be further compromised by the breakdown of communication systems between central offices, warehouses, and retail outlets, making it difficult to manage inventory and demand effectively. To mitigate these risks, more decentralized food storage systems and a network of emergency-ready shops could be established. These would be regular stores that are incentivized to maintain larger storage capacities and emergency power systems.

If the black out is for a longer time period, this will also affect food production. How this will play out was discussed in an earlier post.

Healthcare

The medical system is extremely vulnerable to a prolonged power outage due to its complexity and dependence on other interconnected systems. The healthcare system could function without electricity for approximately a week at most (7). After this point, most patients that need life critical care would likely perish (8).

The decentralized and highly specialized nature of the healthcare sector means it can only briefly withstand the consequences of a power failure. Within 24 hours, the functionality of the healthcare system is already significantly impaired. In the following days, dialysis centers and nursing homes would need to be at least partially evacuated (though it would be unclear where they should be evacuated to). Most doctor’s offices and pharmacies would close. Home emergency call systems and medical devices for home care would become inoperable. The production and distribution of pharmaceutical products in the affected area would cease. The few central hospitals that can maintain their own power supply or have uninterrupted emergency power generators would be overwhelmed trying to compensate for the complete failure of outpatient care and home nursing.

Within a week, the situation in the healthcare sector would deteriorate to such an extent that, despite intensive use of regional aid capacities, a complete breakdown of medical and pharmaceutical care is to be expected (varying a lot by treatment and medicine).

Making the healthcare system more resilient would require larger stockpiles and emergency power supplies. However, this would be extremely expensive due to the system’s decentralized nature and large supplies needed.

Financial system

The financial system demonstrates relatively robust resilience in comparison to other critical infrastructures during a prolonged power outage. This is particularly true for the backend operations, such as data and payment transactions between banks and stock exchanges. These operations, along with data storage and other critical business processes, are generally secured through emergency power supplies or can be relocated to unaffected areas. Stock exchange systems, in particular, have extensive disaster recovery plans in place, allowing them to maintain essential functions throughout the duration of a power outage.

However, the consumer-facing side of the banking system is far more vulnerable. Within a short time after the power failure, the inability to use telephone networks and the internet makes it impossible to conduct financial transactions in the affected area. Many banks that initially remain open after the power outage will close within a few days. With ATMs also non-functional, the cash supply to the population would dry up, making local exchange of goods more difficult. This situation reveals a critical weakness in the sector: the loss of electronic payment capabilities and the dwindling cash supply to the public. As a result, anxiety among the population increases, with people fearing they won’t be able to purchase food and other daily necessities.

The impact on businesses becomes evident towards the end of the first week, with some experiencing liquidity shortages. This is due to the inability to generate income or receive payments from customers, while still having to meet various financial obligations through automated bank payments that continue to be executed despite the power outage.

To mitigate these risks, it would be crucial to develop and implement plans for emergency cash distribution to the public during such crises.

Things we could be doing to increase resilience

Throughout the book Peterman et al. make a variety of suggestions on how we might be able to increase resilience.

Nationalize infrastructure and unify decision making

One problem that has been highlighted in the book is that much of the German infrastructure is in private hands, which makes coordination very difficult. This could be avoided if more parts of the infrastructure would be nationalized. However, this would have to be combined with a clearer hierarchy between the German states and the federal level. Right now responsibilities are split between very different levels of government, which would make coordination challenging during a national crisis.

Rethink the distribution of stocks

The book has identified that for many of our stocks (be it fuel or food), the problem is not the overall amount we have, but the distribution of it. Much of the stock is deployed in few and large storages. While this makes storage cheaper and easier, it also means the stocks are not where they are needed in case of emergency. Therefore, one approach would be to decentralize the storage of fuel and food, so in case of a blackout the transportation is easier.

Microgrids

While it would be difficult to restart the whole electrical grid at once, it is likely possible to quickly introduce microgrids. These could be a single house to a city or even a small region, depending on the local layout of the grid and the available resources. The shift to renewable energy sources is quite helpful here, as those are much more decentralized than previous methods of energy generation. This allows an easier construction of microgrids, which will at least locally allow to maintain some of the critical infrastructure and allow those regions that manage to create those to avoid much of the worst effects of the blackout.

Modeling a blackout

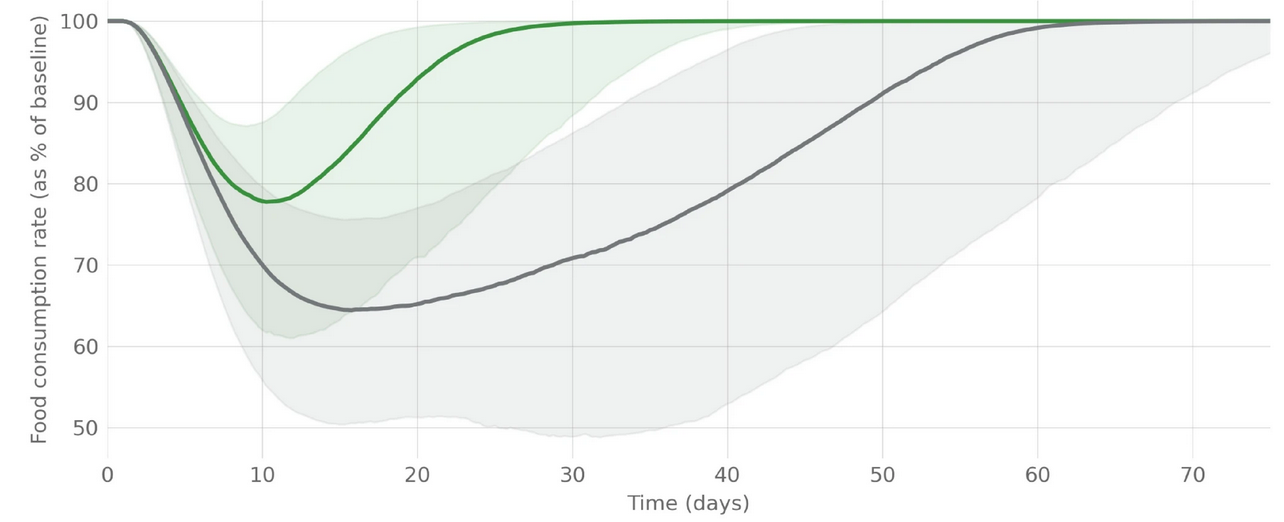

The book underscores the lack of modeling on the effects of blackouts on critical infrastructure. However, a recent study by Blouin et al. (2024) addresses at least a part of this gap by modeling the impact of a multi month blackout on the food system. They developed a system-dynamics model that integrates five critical infrastructures—electric grid, liquid fossil fuels, Internet, transportation, and human workforce—to assess the resilience of the food supply chain. They validated their model against the week-long blackout in Venezuela and found it accurately reflects the observed effects. Consequently, they have some confidence that the model can extrapolate and predict the potential impact on food availability in the United States following a high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) from a nuclear explosion if recovery is relatively quick (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Food availability over time after a HEMP over the United States (Blouin et al (2024)). Green line represents an optimistic recovery, gray a more pessimistic one.

They find that food availability would drop significantly, particularly in the more pessimistic scenario, where it falls below 50% of pre-HEMP calorie levels. The HEMP scenario analyzed by Blouin et al. is similar to the one detailed by Peterman et al., though the former is 60% loss in electric grid availability versus 100%. However, Peterman and colleagues do not provide quantitative estimates. Based on their descriptions, the trajectory would likely be more like the pessimistic scenario or might even result in a total collapse of society.

Moreover, Blouin et al.’s analysis is conducted at the national level, whereas Peterman et al. stress that the impacts of a blackout would vary greatly at the local level, with some regions facing minimal disruptions while others would be severely affected.This means a spatially resolved model would be quite valuable in the future. Looking at how it would influence people with more or less wealth would also be a good addition.

Conclusion

Overall, the book gives quite a devastating account of what would happen after a blackout. People would lose access to food, transportation, healthcare and communication. The water system would probably continue to function at least somewhat and there would probably still be some cash to pay for things locally. The only thing that seems to be really resilient to a blackout is the stock market and your bank account. So, you might not have something to eat, but it seems that you can rest assured the bank keeps track of your debt even if everything around you crumbles (9).

However, there is also at least some positivity here. The authors highlight the potential of microgrids to alleviate much of the problems caused by a blackout. Thankfully, the implementation of such microgrids gets easier every year, as more and more renewable energy comes online and the electrical grid becomes more decentralized.

All this shows that the consequences of blackouts are not well understood, with few models available and significant uncertainty about the outcomes. Peterman et al. even argue that predictions beyond a week are mostly impossible due to our lack of knowledge. More research is clearly needed here.

Endnotes

(1) But there are also high altitude detonations of nuclear weapons causing electromagnetic pulses (HEMPs), space weather events.

(2) There is also the option of satellite phones, but they are not widely available.

(3) Although more renewables would make life more difficult in any catastrophe that blocks out sunlight.

(4) Except after a HEMP.

(5) Longer term there might be some options to pump the gasoline out without electricity.

(6) I find it pretty wild that I have been living in Germany for 34 years, did my PhD in hydrology, but never even heard before that Germany has a complete backup water system.

(7) And less if it was a HEMP.

(8) Some of this happened in a large blackout in Venezuela.

(9) There is probably a metaphor about life under capitalism in here somewhere, but I leave finding it as an exercise to the reader.

How to cite

Jehn, F. U. (2024, October 21). The consequences of large-scale blackouts. Existential Crunch. https://doi.org/10.59350/wnta7-w0c60

References

- Blouin, S., Herwix, A., Rivers, M., Tieman, R. J., & Denkenberger, D. C. (2024). Assessing the Impact of Catastrophic Electricity Loss on the Food Supply Chain. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-024-00574-6

- Petermann, Th., Bradke, H., Lüllmann, A., Poetzsch, M., & Riehm, U. (2011). Was bei einem Blackout geschieht: Folgen eines langandauernden und großräumigen Stromausfalls. edition sigma. https://doi.org/10.5445/IR/140085927