While we generally aim to avoid a collapse, it is crucial to understand the potential recovery time if one occurs. Assessing this is challenging, as it depends on the starting level of complexity, the extent of the loss, and the desired recovery level. History suggests three main stages in the development of civilization from early human societies to a global civilization:

- Hunter-gatherer to early agriculture/pastoralism. The main switch here is that humans become sedentary for the majority of the year. Imagine a small village with some huts and a few fields of crops around them.

- Early agriculture/pastoralism to pre-industrial society. Here the development is towards a society like in medieval England. You have a clear state structure with a defined hierarchy, which controls vast swaths of land. Technology progresses, albeit slowly.

- Pre-industrial to industrial society. The endpoint here is essentially the society we live in right now.

In this post, I will explore the potential timeframes required for each of these transitions. Please take in mind that these are very rough estimates with considerable uncertainties.

Hunter-gatherer to early agriculture/pastoralism

These developments occurred in prehistory, meaning we lack written records and must rely on proxies. A common proxy is radiocarbon dating, which involves analyzing the distribution of carbon isotopes in archaeological organic materials. Since we understand how these distributions change over time, this method allows us to estimate the age of the organic material. By aggregating data from all archaeological evidence, we can create a density function over time. This function serves as a proxy for population levels, assuming that more humans would produce more materials that enter the archaeological record.

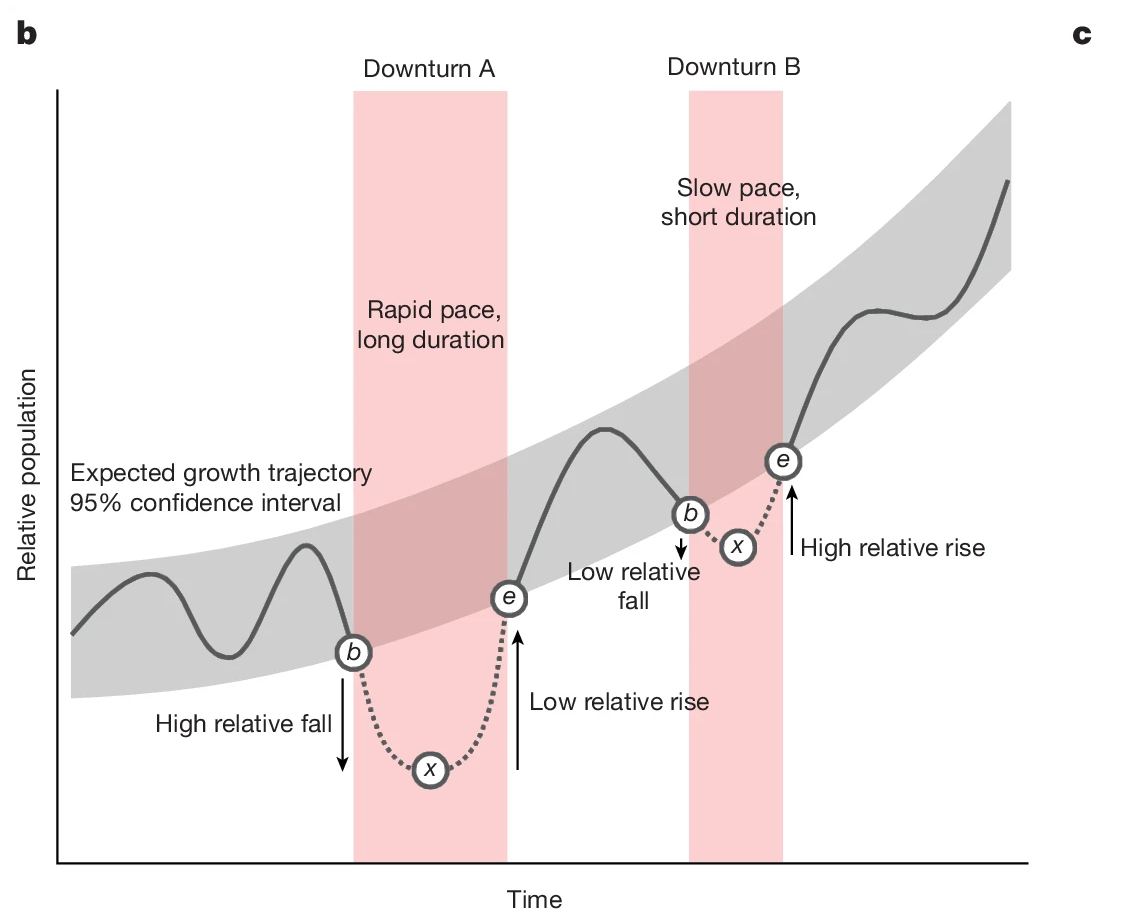

A recent study by Riris et al. (2024) aggregated the radiocarbon data from 16 other studies to try to estimate how human populations developed over the last 30,000 years and how they react to disturbance. They achieved this by fitting population trends over time to a curve, which provided an estimate of expected population at any given point. They then compared the actual estimated population to this long-term trend to identify the intensity and duration of population declines in those societies (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Example trajectory for a population and how the downturns were determined.

This data does not directly indicate how long the transition from hunter-gatherer societies to early agriculture/pastoralism took. However, it provides a proxy. The downturns can be interpreted as the time required to move from a lower level of organization (unable to support higher populations) to a higher level of organization (capable of supporting larger populations). Assuming this proxy works, we can examine the data on population declines. It shows that all regions studied regularly experienced population declines. Most of these declines took 100-500 years to recover from, with longer downturns being rare. This suggests that during early stages of civilization, recoveries could happen relatively quickly. Interestingly, Risis et al. found that the main predictor of recovery time was the frequency of past disturbances. Societies that experienced more frequent population declines tended to recover faster. Since modern civilization has little experience recovering from such collapses, we might face a slower recovery. The longest downturn in the sample was 2000 years. Thus, a more complex downturn takes around 500-2000 years to recover.

We can also look at more qualitative descriptions. For example, Zeder (2011) did a literature review about early agriculture and came to the conclusion that agriculture in the Near East all took around 2000 years from early attempts to established agriculture. However, as the data we have is so sparse, these numbers have high uncertainties. Still, it seems reasonable to assume that a typical transition takes around 2000 years, possibly 500 years if you did not have a complete setback.

This obviously introduces the question: If such a step is so quick, why didn’t humanity develop any kind of civilization earlier? And I think the answer here goes in the direction that the environment has to be suitable to actually develop any kind of civilization and also has to have the incentives to do so (1). This often is not given. Therefore, the estimate here can be understood as the value that I would expect if the conditions are good, like if you have a stable and warm climate as in the holocene.

Likely, the factor relevant here is you have to have an environment which is conducive to agriculture. This not only includes climate, but also things like your local soils or if you have plants and animals available which can be domesticated. This argument is underpinned by a study from Borcan et al. (2021). They collected a dataset which consists of the majority of societies who created states. What they wanted to find out was the question if usually you had agriculture first and then the formation of a state or the other way around. Their results show that this is the case. In pretty much all cases you had first agriculture and state formation only afterwards. Besides this they found that geography, climate, distance to other states and time since the first settlement founded in the area all play a role in the time it takes to go from hunter-gatherers to early states.

Early agriculture/pastoralism to pre-industrial society

The next step for societies is to go from the early seeds of civilization to a highly complex society which has the potential to experience an industrial revolution. Here we already have more accurate and direct data than in prehistory. The best data source is, as is so often the case, the Seshat database (2).

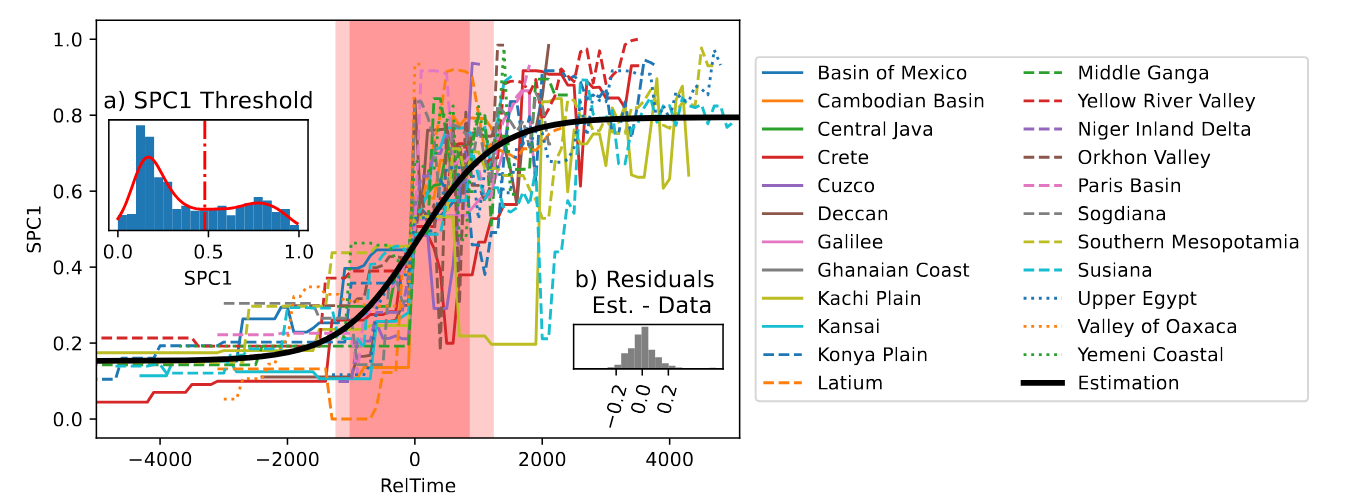

Wand & Hoyer (2024) use data from Seshat to explore the duration of societal development. They observed a temporal pattern in how long it takes societies to progress from low to high complexity (3). To verify this, they analyzed time series data for complexity build-up across various civilizations in Seshat, grouping them by natural geographic areas. A natural geographic area is defined by civilizational continuations within regions, such as the transition from the Roman Republic to the Roman Empire, while treating events like the Roman conquest of Ptolemaic Egypt as an endpoint of independent development.

This approach resulted in 23 historical time series of complexity specific to geographic areas. Wand and Hoyer then examined if these trajectories could be described by a simple mathematical model. They found that a sigmoid curve best represents the data, with a typical growth period of around 2500 years (Figure 2). This period reflects the typical time it takes for a region to progress from early agriculture/pastoralism to pre-industrial complexity, offering a rough estimate for the typical pace of human societal development.

Figure 2: Complexity trajectories of natural geographic areas. SPC1 stands for the first principal component of all the measures in Seshat that measure aspects of complexity. This figure is from the preprint. I used it because it is more easily readable than the one from the published paper.

Pre-industrial to industrial society

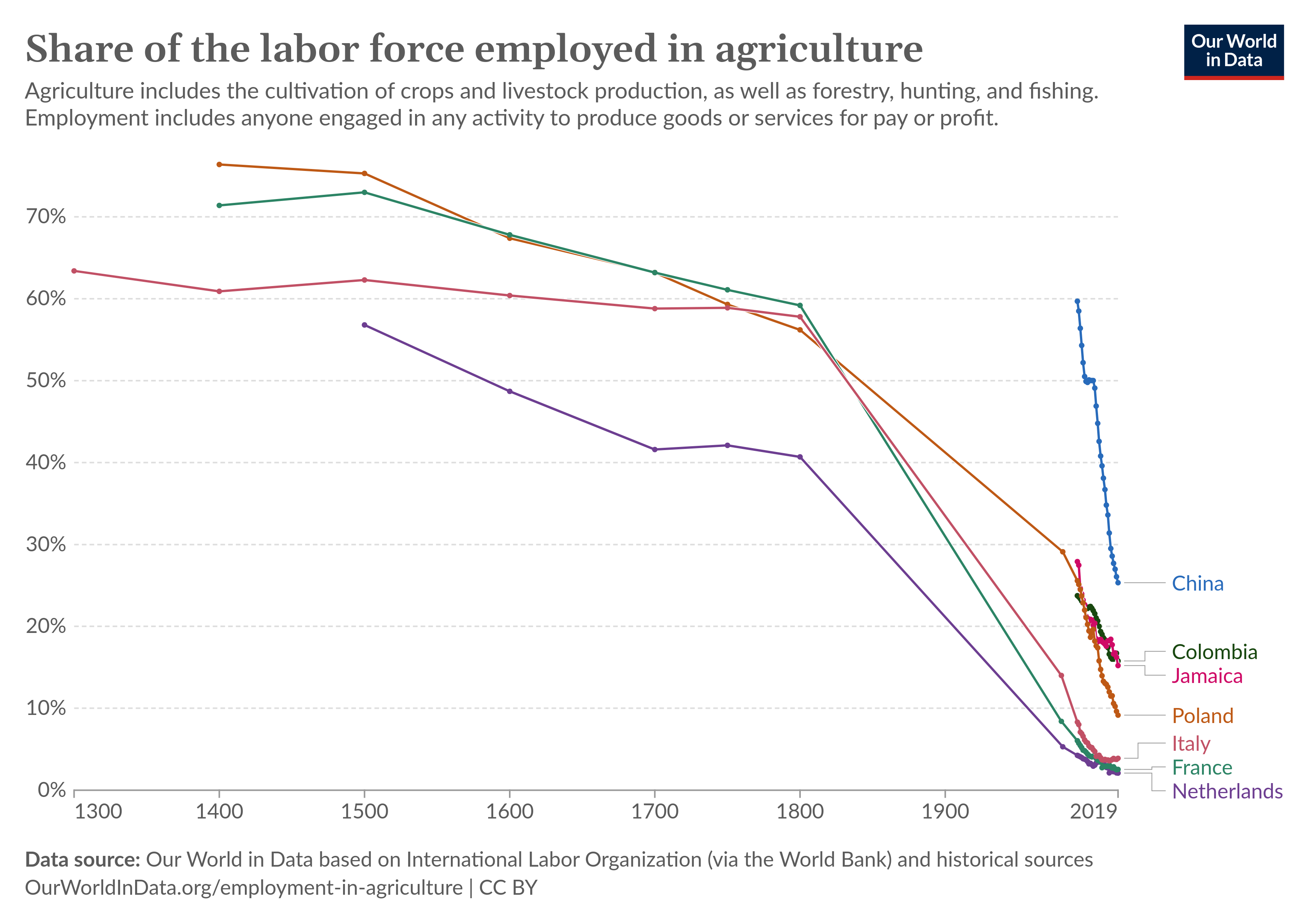

For this last step of the development I was not able to find specific papers. However, Our World in Data provides a plot that shows how much of the workforce was employed in agriculture from 1300 till today (Figure 3).

If you know of important studies I’ve missed here, please email me and I’ll update this article!

Figure 3: Share of labor force employed in agriculture from 1300 till today.

The share of agricultural workers serves as an indicator of industrialization. For countries undergoing industrialization, there has been a significant decline in agricultural employment due to improved productivity. Modern farming techniques enable a single farmer to feed many more people than in the past, allowing others to engage in manufacturing, science, and other fields, accelerating overall development.

Historically, pre-industrial societies had around 50-80% of their population in agriculture, depending on factors like local productivity, climate and soil fertility. These percentages began to drop with early industrialization efforts. The 18th century marks the start of the Industrial Revolution, with a noticeable decline in agricultural employment beginning around 1800, although the groundwork for this shift was laid in the preceding centuries. Some of this groundwork was the increased introduction of capitalistic means of production to the feudal system. This and other processes like more scientific invention which increased productivity allowed people to switch to professions besides agriculture. We can see this in the share of the labor force employed in agriculture. The downward trend begins to start around 1500. This means we can estimate that transitioning from a pre-industrial state to the level of the wealthiest, most developed countries today typically takes around 500 years. From those 500 years, we have around 300 years of slow build-up, then a shift and a highly accelerated progress in the other 200 years.

However, under favorable conditions, this process can be much faster. For instance, China reduced its agricultural workforce from about 80% to 25% in just 50 years by leveraging existing technologies and knowledge from already industrialized nations. Consequently, in the event of a collapse, recovery would more likely follow the typical 500-year timeframe, as we would be missing this boost.

How long would recovery take?

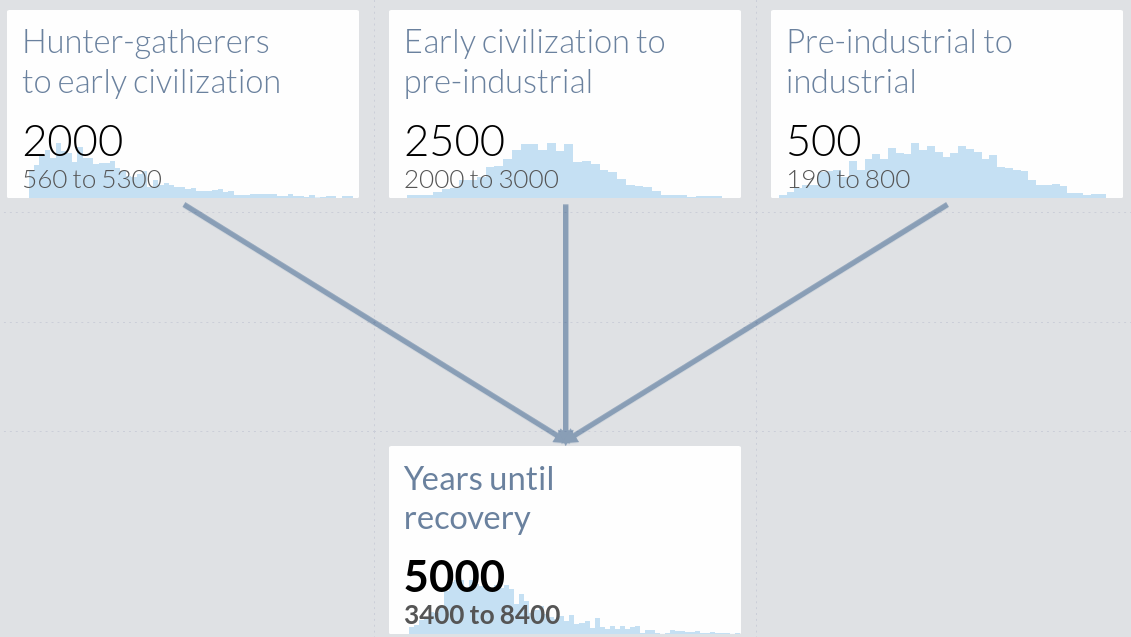

Combining all the factors, I estimate a total recovery time of around 5000 years for the transition from hunter-gatherer societies to modern developed nations, with a range of 3400 to 8500 years (Figure 4). This projection assumes a typical trajectory for each stage under favorable conditions, as well as a lognormal distribution for the first transition to account for the high uncertainty in the tails and normal distribution for the latter two transitions, as we have more data there. Keep in mind that such a lineage from hunter-gatherers to industrial civilization does not really exist. Instead we picked the typical case from three separate categories of development.

Figure 4: Guesstimate of civilizational recovery times. The ranges differ slightly to the values I discuss here, as they are a random sample drawn from a probability distribution.

So, how long would it actually take to happen if we don’t only look at the ideal case? This question is much harder to answer, because it depends on the likelihood of these steps happening. I think the first step has a low chance of happening again. Modern humans have existed for around 200,000 years and if we could really go so quickly to early civilizations, the chance of this happening must be fairly low (4). However, if this was more a question of climate caused incentive structure, it might be a higher chance. Unfortunately, we have embarked on a global climate adventure with uncertain outcomes, so it is questionable if these incentives will still be around in the coming centuries.

The step from early civilization to pre-industrial however seems to be fairly common, as it happened a lot of times, some of which are completely independent from each other, e.g. China, Europe and America. This means if you have a good base established I would think that it is relatively likely to get back to pre-industrial levels.

The last step, going from pre-industrial to industrial, seems to be more difficult again. Arguably it only happened once in Great Britain and spread from there to the rest of the world. Why did it happen in Great Britain and not in other places? This is still pretty much up for debate and until this debate is settled we can’t really tell. An argument that it might be easier next time is that often inventions are limited not by the technological level you are on, but by somebody having the idea. For example, Europeans took a long time to adapt the idea of wheelbarrows, but could have invented them much earlier. On the other hand, we have already used up much of the easily accessible resources like coal or metals. Every following civilization would not have these available to kick start their industrial revolution. However, you could also make the argument that many of the metals are actually easier available now, because we have already refined them and you just have to melt them again. Similarly, the ruins of the past civilizations might inspire humans to recreate today’s achievements, or they might be seen as a cautionary tale, never to be repeated (5).

If you know of important studies I’ve missed here, please email me and I’ll update this article!

Overall, this leaves me a bit ambiguous when it comes to our chances of recovery from civilizational collapse. If we have not completely broken the Earth in the process of collapsing, I would guess that it seems likely that we will make it back to pre-industrial levels in a few thousand years. If we will make it further than that seems quite uncertain, as the environment will simply be quite different to our first attempt at building a global civilization.

Endnotes

(1) For example, this paper suggests that changed seasonality gave the incentive to switch from hunter-gatherers to early agriculture.

(2) A vast historical dataset, which we have already mentioned a bunch of times: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

(3) I also briefly made this observation in an earlier post.

(4) There are numerous conflicting theories regarding the prolonged timeline. The most frequently discussed ones involve climate and psychology. One idea is that civilization emerged following the stable environmental conditions of the Holocene epoch. Another suggests that significant social innovations, possibly involving religion, enabled collaboration on a scale beyond the Dunbar number before civilization developed.

(5) Many of these points are also discussed in the excellent book “The Knowledge” by Lewis Dartnell.

How to cite

Jehn, F. U. (2024, September 24). How long until recovery after collapse?. Existential Crunch. https://doi.org/10.59350/1hh7g-3kv98

References

- Borcan, O., Olsson, O., & Putterman, L. (2021). Transition to agriculture and first state presence: A global analysis. Explorations in Economic History, 82, 101404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2021.101404

- Riris, P., Silva, F., Crema, E., Palmisano, A., Robinson, E., Siegel, P. E., French, J. C., Jørgensen, E. K., Maezumi, S. Y., Solheim, S., Bates, J., Davies, B., Oh, Y., & Ren, X. (2024). Frequent disturbances enhanced the resilience of past human populations. Nature, 629(8013), 837–842. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07354-8

- Wand, T., & Hoyer, D. (2024). The characteristic time scale of cultural evolution. PNAS Nexus, 3(2), pgae009. https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae009

- Zeder, M. A. (2011). The Origins of Agriculture in the Near East. Current Anthropology, 52(S4), S221–S235. https://doi.org/10.1086/659307