Democracies have a stronger incentive to keep their general population content compared to authoritarian regimes, as the political elite’s survival is more directly linked to the general population through elections. In a previous post, we explored the relationship between participation, inclusion, and democracy with societal resilience. We found that historically, more participatory societies tended to recover better from major catastrophes, such as large volcanic eruptions. Additionally, democracies have generally managed crises better than non-democracies in recent decades. In this post, I will discuss further reasons why democracies are crucial for societal resilience and forward-thinking decision-making. However, I will also argue that the number of democracies is currently decreasing and we must address this to ensure greater safety during global catastrophes.

Democratic processes favor societal resilience

In addition to the advantages in the previous post, democracies also tend to be more forward looking when it comes to global risks. For example, a variety of democratic countries have national risk assessments which include assessments of global hazards (Table 1).

Table 1: Examples of countries that cover global catastrophic risks in their national risk assessments. “Tangentially” refers to the threat being mentioned, but not discussed further.

| Country/Hazard | Nuclear Weapons | Artificial Intelligence | Climate Change | Near Earth Objects (e.g. Meteor) | Geomagnetic Storm | Pandemics | Supervolcanic Eruptions | Link to risk assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Switzerland | Tangentially | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Link |

| United Kingdom | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Link |

| Netherlands | Tangentially | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Link |

| New Zealand | Tangentially | Tangentially | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Link |

| Canada | Tangentially | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Tangentially | Link |

Not all countries listed here consider all risks, nor do all democracies have such national risk assessments. However, I am not aware of similar documents from any non-democratic states. These might exist without being public, but it is important that such assessments are easily available, so blind spots can be identified and taken care of. A great example of how this can play out is described in Boyd & Wilson (2021), which looks at New Zealand’s current plans and policies related to global catastrophic risk. They find them lacking and make a variety of suggestions on how they could be improved. Such an assessment and critique is only possible when plans are publicly available and a government exists that is open to feedback from their constituents. For example, the New Zealand assessment was previously classified, and once published, received harsh criticism.

In recent decades, citizens’ assemblies have emerged as a notable example of how more democratic processes can generate forward-looking suggestions. A citizens’ assembly gathers a demographically representative group of people, provides them with the scientific information on a given topic, and allows ample time for discussion on specific societal issues. The outcomes of these assemblies are typically nuanced and often result in workable compromise proposals. For instance, in Ireland, a citizens’ assembly was tasked with proposing new regulations for abortion, which was mostly illegal in Ireland up to this point. After careful deliberation, the assembly recommended a significantly more liberal approach, leading to a referendum where the proposal was approved by a clear majority. This case demonstrates how citizens’ assemblies can effectively navigate delicate issues and achieve majority support.

To make a more empirical argument for more democratic processes like citizens’ assemblies we can look at a recent study by Lage et al. (2023). They compiled the results of all citizen assemblies in the European Union focused on climate change mitigation. Their findings show that the assemblies’ recommendations are generally much stricter than those currently implemented by their respective governments, especially regarding regulation. This indicates that a representative group of citizens often reaches forward-looking conclusions aimed at ensuring societal safety and preparedness. Although there haven’t been any citizen assemblies on global catastrophic risk yet, I am optimistic they would provide valuable recommendations for better preparedness.

Another point on the advantage of democracies when it comes to resilience is maintaining peace. Historically, established democracies rarely to never (depending on how you define an established democracy) go to war against each other. A review of the current empirical evidence by Reiter (2017) concludes that this is indeed the case. They conclude that, even when accounting for factors like national interest, economic conditions, and gender norms that might influence a country’s decision to go to war, the primary factor remains whether the country is an established democracy. Tomz & Weeks (2013) tried to determine why being a democracy has such a strong influence on the decision to go to war. Based on past literature they identify public opinion against striking other democracies as the main reason. To verify this hypothesis they conducted public opinion polls in the United Kingdom and the United States. These opinion polls asked people if they would support a military strike against a country which is developing nuclear weapons. No specific country was named, but additional information was provided if the country was a democracy or not, if it was in a military alliance with the UK/US and if the forces of that country were equally or half as strong as the forces of the UK/US. If the country was a democracy this decreased the willingness to strike by around 20 to 40 %. While this is just one datapoint it provides backing to the idea that public accountability could be a strong factor here.

Comparison to authoritarian regimes

But democracies are not only better at maintaining peace, they also tend to fare better when a geopolitical conflict breaks out. Brands (2018) used a review to explore how democracies and authoritarian regimes tend to approach great-power conflict and their conflicting worldviews in general. Economically, democracies consistently outperform autocratic regimes in building the wealth essential for strategic success. This stems from the free exchange of information, stable legal frameworks, and protection of individual and property rights that foster investment and innovation. Democracy’s decentralized power structure helps avoid rash economic decisions with potentially disastrous consequences, like China’s Great Leap Forward or going to war unprovoked. Additionally, democratic militaries tend to perform at higher levels than their authoritarian counterparts, as they typically employ professional forces comfortable with delegated authority and operational flexibility, while authoritarian regimes try to centralize power to be safe from coups.

Authoritarian regimes may boast advantages in speed and decisiveness, democracies excel in sustainable decision-making processes over the long term. The very features that can make democratic governance appear slow and inefficient—checks and balances, power transitions, and robust public debate—are precisely what enable reasoned deliberation and necessary course corrections. Conversely, authoritarian systems, which concentrate power in a small elite while stifling debate, are more prone to significant errors when leaders make emotional or illogical decisions without adequate feedback mechanisms. This long-term decision quality may prove especially critical when addressing complex global catastrophic risks that require sustained attention and adaptive management rather than merely swift action.

A similar point is often made around the ability of autocrats to govern for the long term. Here the argument is that democracies fail to foresee problems over long time horizons, because they can only think along their election periods (so mostly 4-5 years), while autocratic regimes are not bound by this and can therefore plan for decades ahead. The validity of this argument is explored in Millemaci et al. (2024). To study this, they looked at economic growth and long term positive societal outcomes (think education, health, public transport, taking public opinion into account) and compared it between democratic and autocratic countries. For economic growth they find results similar to previous literature, meaning that generally democratic countries outperform autocratic regimes. However, autocratic regimes have heavier tailed distributions. This means that while autocratic regimes are generally worse when it comes to economic outcomes, they also represent the largest outliers for both very slow (or even negative economic growth), but also very fast growth. But economic growth in and of itself is not something we really care about, because a higher GDP does not automatically mean that people are better off. This makes the study of Millemaci and co-authors especially interesting, as they also take into account positive societal outcomes in addition to economic growth and here the results are very clear. Democratic countries across the board deliver better societal outcomes to their citizens in things like health or education. This finding even stays robust when you control for how rich the country is in general. Therefore, Millemaci et al. conclude that there are no benevolent dictators who govern for the long term. They might be able to boost economic growth, but this only means they have more riches for themselves and their cronies. Their population would have a much better quality of life, if their country were democratic instead.

Democracies seem to be stagnating or even decreasing

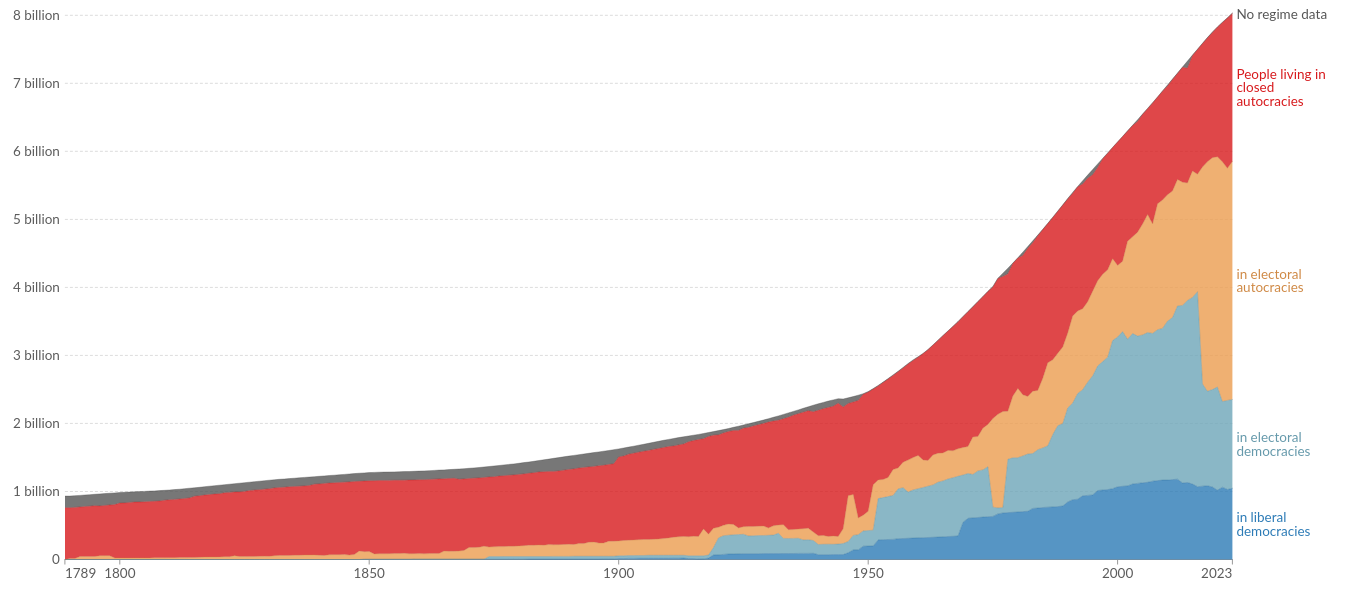

We thus know that past societies fare better when they are more participatory, that democracies handle disasters better, generally don’t fight each other and that the very democratic processes like citizens’ assemblies tend to produce forward looking proposals subject to public oversight, which would make our societies more resilient to future hazards if implemented. This means it would be very advantageous from the standpoint of resilience against societal collapse if more states become democracies and if the existing democracies become more democratic. Unfortunately, this does not seem to be the case right now (Figure 1) (1).

Figure 1: Number of people living in states which are democratic/autocratic from 1789 till today. Source: Our World in Data

In the last decade the number of electoral democracies has mostly stagnated, while the number of liberal democracies has declined. Here, “electoral democracies” means responsive governance through free and fair elections, ensuring that political and civil society can function without interference and that the media can present diverse views. Liberal democracies in addition prioritize the protection of individual and minority rights from state and majority overreach. This involves enforcing civil liberties, maintaining a strong rule of law, and implementing checks and balances to limit government power. While both types value electoral processes, liberal democracies add an additional layer of safeguarding personal freedoms and institutional integrity. So, when it comes to making sure that we are safe from future hazards, liberal democracies are possibly the safer bet, as they focus more on keeping everyone safe against all kinds of harm.

The reasons for this decline in democracy are likely manifold. A review by Loughlin (2019) argues that this has been a slow and somewhat hidden process. The loss of democracy today does not happen by a coup, but by a gradual degradation of democratic processes. A prime example is Hungary. A country that is theoretically a democracy, but the rule of Victor Orban has over the years dismantled all checks and balances on his rule, while also bending the electoral process in such a way that it is almost impossible for him to lose. Similar attempts can be seen in many other established democracies as well. For example, the “Alternative für Deutschland” in Germany or the MAGA movement led by Donald Trump in the United States. While we can see the process of democratic decay relatively clearly, why exactly this is happening now is more uncertain. Loughlin provides some main suspects:

- Globalization: Rising globalization has undermined states’ ability to regulate their own economy, as they are exposed to many forces out of their control. This removes important options for national self-determination.

- Inequality: Economic inequality in many countries has been rising over the last decades, making life worse for many citizens in democracies. This decreased trust in traditional democratic processes, which promised people a better life.

- Focus on the individual: Neoliberal capitalism, which is the main form of economics in almost all democracies, focuses strongly on individual freedom. In combination with increased migration and inequality this leads to less group cohesion and identification with the collective. However, this identification with the collective is important to see democratic processes as valuable, even if they don’t always exactly end up doing what you personally would prefer.

- Economic power of companies: Gigantic companies like Amazon or Apple have increasing influence on governmental politics via lobbying. This frustrates voters, because they see that their preference is not taken into account if it goes against the interest of major companies.

While these are significant claims, they are frequently echoed in other papers examining the relationship between societal conditions, inequality, and democracy. For instance, Centeno & Cohen (2012) discuss neoliberalism’s history and emphasize similar issues as Loughlin. A more concrete example of how economic power enables large companies to influence the political system is provided by Supran et al. (2023). They examined ExxonMobil’s company records, showing the company knew by the early 1980s how much fossil fuels would heat the planet. These models accurately predicted recent decades’ warming. Despite this, ExxonMobil used its influence to spread misinformation that contradicted their findings and to persuade policymakers to avoid legislation that would impede their business.

When we look in aggregation at all these factors they have one thing in common. They are all consequences of neoliberal capitalism, which aims to minimize state power and favors markets as the main mechanism for societal coordination.

Ending up in a democracy is not the default arc of history

Democracies enhance our resilience, but they are somewhat in decline. This issue would be less concerning if we had reason to believe most states eventually become democracies. To those of us living in democracies, they seem clearly better to the alternatives. However, a paper by Treisman (2020) challenges the conventional narrative of democratization as a deliberate, rational choice. By examining historical transitions to democracy, he argues that most were unintended consequences rather than planned outcomes. Treisman categorizes democratic transitions into three main types:

- Democratization by mistake: The most common scenario, where autocratic regimes inadvertently create conditions for democracy through:

- Mishandling domestic opposition (e.g., ill-advised concessions or electoral mismanagement)

- Internal regime failures (e.g., losing support of security forces or elites)

- Foreign policy blunders

- Deliberate democratization: A less frequent case, where elites purposefully choose democracy to:

- Prevent revolution through promised wealth redistribution

- Garner public support for wars

- Increase incumbent popularity

- Resolve political deadlocks

- Achieve other goals like avoiding violence or securing international aid

- Unintended but unavoidable democratization: Situations where ruling elites actively resist democratization but fail to prevent it.

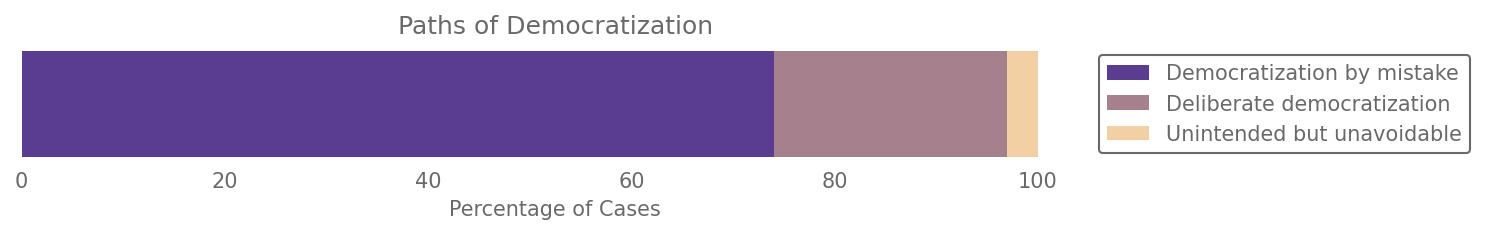

Treisman’s analysis (Figure 2) reveals that the majority of historical democratizations fall into the “accidental” category, suggesting that democracy often emerges as an unintended consequence of autocratic missteps rather than through deliberate action.

Figure 2: Percentage of cases for the different pathways to democratization.

This implies that democratization is not a given, as it depends on errors by rulers, which are possible but not certain. Additionally, revisiting the previous section’s argument, democracies may have once been an attractor state for many autocratic regimes, but this trend has shifted in recent decades.

But there is also some evidence that democracies seem to be a strong attractor to get back to, once you have been a stable democracy for a while. This is explored in Nord et al. (2025). They wanted to understand how democracies fare in the present “wave of autocratization”. To do so, they looked into history, as this is not the first time democracies face headwinds. They used a dataset of democracies from 1900 to 2023, which tracked how democratic these countries were over this period.

This provided them with a time series for every country. In this timeseries they looked for breaks when countries suddenly are becoming less democratic or less autocratic. Using this approach they found a process which they simply call “U-Turns”. This means that a given country turned toward autocracy for a while, but then quickly reversed course and became more democratic again.

They identify 102 of these U-Turn episodes. Which is significant, because this represents 52 % of turns towards autocracy. This means roughly half of all democratic backsliding gets quickly resolved again (meaning in less than five years). And it gets even better, because if we only look at the last 30 years 73 % of all turns towards autocracy got quickly reversed. So, even in the present day we apparently have a good chance to save our democracies. Additionally, in recent decades these U-Turns mostly start before a country becomes an autocracy, hinting that democracies got more resilient against the call of autocracy. Though, it remains a bit unclear why exactly.

Saving democracies by making them more democratic

To summarize, democracies are important, but in decline and if we lose them, there is no guarantee that we will get them back. This clearly leads to the question: How do we keep our democracies? The abovementioned review by Loughlin also provides some potential answers here. Overall, it can be summarized as: our democracies suffer from not being democratic enough. Mostly we offer only a chance to vote every few years and that is the only interaction most citizens have with their democracy. More democratic in this context would mean increasing participation, representation, and equality in decision-making processes within a society. Possible interventions here include citizens’ assemblies, participatory budgets and using new technologies to make it easier to sample the opinions of citizens (2). As many of the problems are also rooted in inequality, more equal access to resources for example via a universal basic income also could be promising (3).

No matter what we do, it seems quite important to me that we manage to maintain strong democracies if we want to have a good chance to make it through the hazards we will face.

Endnotes

(1) There is some recent research that argues that democracies are not actually backsliding, but stable. However, most research I have seen argues in the direction of democracy currently being in decline. Either way, the argument I am making here is mostly the same if democracies are not declining, but stable.

(2) Taiwan comes to mind here.

(3) These are all quite abstract measures, but there is also potential something that individuals can do. The German organization Effektiv Spenden has created a fundS that funnels donations to organizations which strengthen democratic processes.

How to cite

Jehn, F. U. (2024, July 26). Democratic Resilience. Existential Crunch. https://doi.org/10.59350/2h1aw-4w266

References

- Boyd, M., & Wilson, N. (2021). Anticipatory Governance for Preventing and Mitigating Catastrophic and Existential Risks. Policy Quarterly, 17(4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.26686/pq.v17i4.7313

- Brands, H. (2018). Democracy vs Authoritarianism: How Ideology Shapes Great-Power Conflict. Survival, 60(5), 61–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2018.1518371

- Centeno, M. A., & Cohen, J. N. (2012). The Arc of Neoliberalism. Annual Review of Sociology, 38(Volume 38, 2012), 317–340. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150235

- Lage, J., Thema, J., Zell-Ziegler, C., Best, B., Cordroch, L., & Wiese, F. (2023). Citizens call for sufficiency and regulation—A comparison of European citizen assemblies and National Energy and Climate Plans. Energy Research & Social Science, 104, 103254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2023.103254

- Loughlin, M. (2019). The Contemporary Crisis of Constitutional Democracy. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 39(2), 435–454. https://doi.org/10.1093/ojls/gqz005

- Millemaci, E., Monteforte, F., & Temple, J. R. W. (2024). Have Autocrats Governed for the Long Term? Kyklos. https://doi.org/10.1111/kykl.12425

- Nord, M., Angiolillo, F., Lundstedt, M., Wiebrecht, F., & Lindberg, S. I. (2025). When autocratization is reversed: Episodes of U-Turns since 1900. Democratization, 0(0), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2024.2448742

- Reiter, D. (2017). Is Democracy a Cause of Peace? In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.287

- Supran, G., Rahmstorf, S., & Oreskes, N. (2023). Assessing ExxonMobil’s global warming projections. Science, 379(6628), eabk0063. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abk0063

- Tomz, M. R., & Weeks, J. L. P. (2013). Public Opinion and the Democratic Peace. American Political Science Review, 107(4), 849–865. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055413000488

- Treisman, D. (2020). Democracy by Mistake: How the Errors of Autocrats Trigger Transitions to Freer Government. American Political Science Review, 114(3), 792–810. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000180