Historical evidence shows that human civilizations repeatedly engaged in self-destructive behaviors in the past, especially in terms of resource overuse (1). Today, we could point to climate change, as a clear example of self-destructive behavior. In a recent paper, Søgaard Jørgensen et al. (2023) coined the term “anthropocene traps” for this type of behavior, building on the concept of evolutionary traps from biology. They show how these traps are endangering the stability of our civilization, how deep we are already in these traps, and what we might do to avoid them.

What is an evolutionary/anthropocene trap?

In biology, evolutionary traps refer to behaviors where an animal’s instincts lead them to prefer actions that harm their survival and reproduction. This occurs when a once adaptive trait becomes maladaptive in a changing environment, often due to human influence. A classic example is the giant jewel beetle. These kinds of beetles are large, brown and shiny and therefore the male beetles are attracted to large, brown and shiny things. Unfortunately, beer bottles fit this description, causing the beetles to try mating with them, which decreases their survival and reproductive success.

In humans, an example is our preference for sugar. This was beneficial in our ancestral environment where sugar was scarce, but in modern society, it can lead to harmful overconsumption. Unlike animals, humans can also exhibit these behaviors on a cultural level. This means we engage in culture-based behaviors that seem sensible to individuals or local groups but harm our overall societal well-being and functionality (2). This is what Søgaard Jørgensen et al. call “Anthropocene traps.” Unlike biological evolutionary traps, human cultural evolution follows runaway trajectories. This means that biological traps are somewhat fixed by the interaction of environment and genetics, while anthropocene traps are constantly self-reinforcing through feedback mechanisms. Therefore, in the case of humans the issue is not a lack of evolution but the inability to escape the harmful path that our cultural evolution takes.

How did they go on identifying the traps?

To identify different types of traps, several expert workshops were held at the Stockholm Resilience Center. During these workshops, experts first identified 61 key processes that they believed significantly influence the trajectory of the Anthropocene. They then examined which of these processes exhibited trapping dynamics. The criteria for a trap were:

- It evolves from an initially adaptive process.

- At the global level, it shows signs of undesirable impacts on human well-being or is hypothesized to show such signs in the future.

- It has a trapping mechanism that makes it harder to escape from negative impacts once activated. Based on these criteria, they identified 14 traps.

What kind of traps are there?

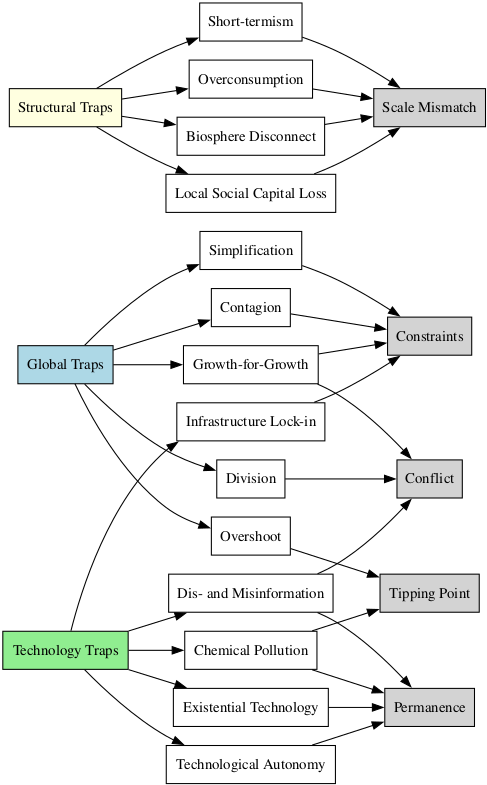

The 14 traps belong to three broad categories: structural traps, global traps, and technology traps (Figure 1). These categories describe the main evolutionary dynamic which pushes them forward. Note that traps can also interact with each other. Søgaard Jørgensen et al. find that these interactions are mainly reinforcing, e.g. higher levels of organization, leading to more technology development. Let’s look at these three categories.

Figure 1: Overview of the kind of traps (left), the traps (middle) and the trapping mechanism (right). Own figure produced from table 1 in Søgaard Jørgensen et al. (2023).

Global traps

Søgaard Jørgensen et al. (2023) explain global traps as problems that come from growing social complexity and cooperation on ever larger scales. Human societies have become more organized to solve problems; over time this connects us globally but also increases our impact on the environment. This leads to a cycle where more organization brings specialization, efficiency, and growth, with the net effect being higher resource demands. If these resources are not easily available to you, these demands can be met by taking more resources by conflict or more cooperation (3).

This cycle has several risks. Specialization reduces diversity and resilience, focusing on growth can harm well-being, and using more resources risks surpassing ecological limits. The instability of global cooperation can lead to conflicts, and increased connectivity can spread diseases and other shocks.

In the past 30 years, these traps have worsened, causing more frequent and severe ecosystem shocks, disruptive economic growth, economic crises, rising inequality, worsening environmental crises, increased political tensions, and more frequent global disease outbreaks. This push for higher organization and efficiency makes the global system more vulnerable to various crises.

Technology traps

Technology traps are problems arising from our use of technology. Humans use technology to improve their lives, but this can have unintended negative effects.

Søgaard Jørgensen et al. identified five technology traps with two reinforcing dynamics. First, technological innovations often create new environmental or social challenges that are addressed with more technology. Second, as technologies evolve, they become more complex and interlinked.

These technology traps often result from solving other issues. The two fundamental traps are infrastructure lock-in, where existing technologies become hard to change due to sunk costs, and chemical pollution from new materials. The other technology traps are the risk of self-extinction from powerful technologies like nuclear weapons, the danger of autonomous technologies not aligning with human goals, and the spread of misinformation due to the exponential growth of digital information.

Structural traps

Structural traps stem from the rapid global changes driven by the dynamics of global and technology traps. Structural traps occur either when changes happen too quickly for human behaviors to be sustainable, or from masked effects of globalization. This masking can either be temporal and spatial: temporal masking occurs when actions now affect the future (temporal traps), and spatial masking occurs when local actions impact globally (connectivity traps).

The main temporal trap is short-term focus, where short-term economic growth and quick fixes overshadow long-term sustainability. Connectivity traps include processes like the separation of sites of consumption and production or an increasing fraction of the population living in cities and not realizing that the biosphere around their cities is disrupted as they don’t have easy access to it.

How do we end up in traps?

All 14 traps follow a similar trajectory in how they evolve over time. Søgaard Jørgensen et al. thinks this trap evolution happens in three distinct steps:

- Initiation and scaling: The trap comes into being, as a new technical or social solution is applied for a problem. As the solution is helpful it gets adopted on larger and larger scales. These solutions often address local and short-term consequences, but their effects can be global and long-term.

- Masking: The trap increases in size, but the effects are not yet visible, as they are separated from the solution in either time, space or both.

- Trapping: In this stage the trap is sprung and it gets increasingly harder to escape. This happens via five main trapping mechanisms.

Trapping mechanisms

- Permanence: Once you bring a technology into the world, it is hard to remove again. For example, nuclear weapons or many chemicals.

- Constraints: These are factors that make it difficult to change the state you are in. For example, the major focus of many international organizations on economic growth over other metrics.

- Tipping points: A tipping point is a point in the system where any additional pressure will make it difficult to impossible to go back to how it was before (4). For example, the dieback of the Amazon rainforest due to climate change.

- Conflict: Human cooperation often relies on an outgroup as a focus point. On a global scale this does not exist and makes cooperation on that level very difficult.

- Scale mismatch: The cause and effect are hidden by time or distance. For example, buying imported goods from countries with lax environmental regulation.

What is the current state of the traps?

After identifying the traps and their mechanisms, Søgaard Jørgensen et al. used globally available data and further expert elicitations to understand the traps. They find that 12 out of the 14 traps are already in their trapping stage and highlight the current state.

Global traps: Institutional lock-ins to intensive production methods limit our ability to make production ecosystems more resilient. Delayed effects between emissions and global warming mean we are already on track for a 1.5°C rise and above. National goals often conflict with global sustainability efforts, and many countries benefit from not cooperating. The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the difficulties in managing interconnected systems.

Technology traps: Dependence on fossil fuels, chemical pollution, and nuclear weapons creates hard-to-escape traps. The long-term and combined effects of pollutants are not well understood. The spread of nuclear arms has locked us into serious risks, making disarmament difficult. Autonomous technology and disinformation are emerging issues, with growing concern about their future risks. However, many potential failures of AI and robotics are still hidden, and efforts to regulate disinformation seem unlikely to succeed soon.

Structural traps: Here the main problem is the lock-in to short-term growth strategies that prioritize individual gains over collective good. Economic growth is still tied to high consumption, especially in wealthy countries, making it hard to align local actions with global impacts.

An interesting question is whether these issues are specifically related to the Anthropocene or are more general features of human societies. For some of these traps, it appears to be the latter. For instance, overconsumption has been prevalent in many historical societies. However, I believe most traps are characteristic of our modern civilization, particularly due to the reliance on capitalistic markets for resource allocation. While markets generally allocate resources efficiently, they frequently encounter the problem of negative externalities—unaccounted-for negative impacts on third parties. For example, if a farmer overuses fertilizers and harms the surrounding environment, this cost is not reflected in the price of their products because the farmer doesn’t pay for the environmental damage. Many of these traps, such as chemical pollution, are negative externalities. Society, not the responsible company, often bears the cleanup cost. Similarly, markets tend to incentivize short-termism, as future damage is typically not factored into current prices.

How does this relate to progress?

Reading this, you might think that Søgaard Jørgensen et al. view progress and technology purely negative. However, their argument is more nuanced. They suggest that humanity often ends up in harmful, self-reinforcing cycles due to how we organize our societies. These cycles cause harm, not the original goals of progress or technology. Therefore, the solution isn’t to revert to a pre-industrial lifestyle, but to improve our decision-making processes. For instance, many issues they mention could be mitigated by stronger democratic institutions, increased global cooperation and moving away from markets as our coordination mechanism if they cannot account for severe externalities.

How could we escape?

So far, this sounds like humanity is in a dire spot when it comes to anthropocene traps. However, Søgaard Jørgensen et al. try to end on a more positive note and describe how they think we might be able to overcome the traps. The main concept they present here is evolvability. This means changing our own cultural evolution into specific directions, so over time we become better adapted to the environment we have created ourselves, with the ultimate aim being global sustainability. To get to this state, they propose five aspects of evolvability we should work on:

- Recognizing traps: Right now we often only realize the traps when we are already in it. This means we have to increase the awareness that such things exist in the first place and create agendas like the Sustainable Development Goals, which have the explicit aim of making sure that we are creating an environment that is long term sustainable.

- Measurement and foresight: Often we realize too late that we are in a trap, because we have not monitored the pathways on which the harm happens. For example, the measure of GDP does not capture the damages we do. This means we have to develop measures that more accurately reflect the effects we have on our environment and use them for our decision making.

- Reorganizing and innovating: Many of our institutions are still organized around neoliberal ideals of small states, lax regulation and high economic growth. We must phase out these maladapted organizations and replace them with new ones that are better adapted to the challenges ahead.

- Being prepared for the unknown: Even if we work on all the other points, it is likely that we will be faced with unprecedented challenges we did not see coming. This means we have to have slack capacity in our system, which can be used quickly if something unexpected happens.

- Navigating conflict: Our lack of an out-group on the global scale makes it difficult to cooperate. We therefore need new narratives which could bring us together. For example, the common enemy of humanity could be the hostility of outer space and the difficulty of living on a limited planet (5).

These are all high-level goals, but the paper makes one concrete suggestion regarding trap interactions and priorities. It identifies three traps—global division, short-termism, and overconsumption—that each negatively impact eight other traps. Solving these three traps could significantly reduce system pressure.

Similar ideas

A similar concept to those of anthropocene traps is the death spiral as introduced in Schippers et al. (2024). They define death spirals as “a vicious cycle of self-reinforcing dysfunctional behavior characterized by continuous flawed decision making, myopic single-minded focus on one (set of) solution(s), denial, distrust, micromanagement, dogmatic thinking and learned helplessness”. They think historically there are two main things that cause such a societal death spiral: 1) rising wealth inequality and 2) dwindling resources. In contrast to Søgaard Jørgensen et al. (2023) this more concrete problem identification, also provides a more concrete solution: reducing inequality to increase general societal resilience. This finding also fits with other arguments we have discussed on this blog. Especially, the research around democracies shows that decreasing wealth inequality is a very important factor to create a society resilient against catastrophes.

Another other recent paper by Rockström et al. (2023) makes additional suggestions, which seem very in the spirit of the paper presented here. Rockström et al. looked at the stage of the current Earth system and its components like climate or land use and propose a range of safe and just Earth system boundaries, which would maintain the long term stability and resilience of the Earth system, while also trying to minimize the exposure of each human to the detrimental effects of Earth system change. If we would manage to stay in these boundaries, many of the traps described would become much less severe or would even be completely disarmed.

Endnotes

(1) This is especially emphasized in explanations like the one by Jared Diamond, but it can be found in pretty much all societal collapse schools of thought (see the intro post to this living literature review).

(2) The economics equivalent would probably be something like a prisoner’s dilemma.

(3) This sounds quite similar to the diminishing returns of complexity idea by Joseph Tainter, explained here.

(4) We discussed tipping points in detail in an earlier post.

(5) Maybe it’s just me, but this made me think of Pale Blue Dot: “…on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.”

How to cite

Jehn, F. U. (2024, June 20). Anthropocene traps. Existential Crunch. https://doi.org/10.59350/7nnaa-1vr81

References

- Rockström, J., Gupta, J., Qin, D., Lade, S. J., Abrams, J. F., Andersen, L. S., Armstrong McKay, D. I., Bai, X., Bala, G., Bunn, S. E., Ciobanu, D., DeClerck, F., Ebi, K., Gifford, L., Gordon, C., Hasan, S., Kanie, N., Lenton, T. M., Loriani, S., … Zhang, X. (2023). Safe and just Earth system boundaries. Nature, 619(7968), 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06083-8

- Schippers, M. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., & Luijks, M. W. J. (2024). Is society caught up in a Death Spiral? Modeling societal demise and its reversal. Frontiers in Sociology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2024.1194597

- Søgaard Jørgensen, P., Jansen, R. E. V., Avila Ortega, D. I., Wang-Erlandsson, L., Donges, J. F., Österblom, H., Olsson, P., Nyström, M., Lade, S. J., Hahn, T., Folke, C., Peterson, G. D., & Crépin, A.-S. (2023). Evolution of the polycrisis: Anthropocene traps that challenge global sustainability. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 379(1893), 20220261. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2022.0261