If we want to learn about human society’s resilience or fragility, it’s helpful to learn from our species’ prior experiences. The trouble is, since collapse is a relatively rare phenomenon, we’re short on data. One way we can get a bigger sample is by looking to the increasingly distant past, but how deep into the past can you go and still get a useful sample?

Humans in their modern form have lived for around 200,000 years on this planet. The global society we have now is very unlike the hunter-gatherer tribes of the deep past, but we’re still the same species. There is no clear break between them and us. Still it seems obvious that the further you go in the past, the more difficult it is to learn something applicable to today’s global society. To start, consider this argument, adapted from Toby Ord’s “The Precipice”:

- Humans have existed for a long time

- Natural existential risks (think supervolcanoes, asteroids, pandemics, and other non-human dangers) did not kill us all

- Therefore, the danger of natural existential risks must be low.

This sounds like a neat and tidy argument, but a 2023 paper by Seth Baum challenges the validity of thinking about natural existential risks in this way.

Against natural existential risks

Baum challenges Ord’s assumptions in a two step argument:

1) There are no “natural” existential risks. Risks exist in interaction with society

Ord’s argument assumes natural existential risks occur independently of human society, which is somewhat true. However, in more recent discussions on existential risk, the focus has shifted towards considering risk in terms of three main aspects: hazard, exposure, and vulnerability. Hazard refers to the source of the risk, like an asteroid impact, for instance. Exposure pertains to how the risk interacts with society. For example, in the case of an asteroid impact, it could lead to a drop in temperatures, which would decrease the food available for the society. Vulnerability relates to how society is affected by the hazard through exposure. Importantly, vulnerability can be influenced by society itself. To stay with the example of the asteroid impact, we could develop resilient foods beforehand, for example, so we are less reliant on traditional agriculture when the temperature drops (1).

2) The track record of the human species does not tell much about the extinction risk that a global civilization faces.

This decomposition of existential risk implies using the last 200,000 years to assess the probability of natural existential risks is the wrong reference class. Hunter-gatherer tribes are just too different from our global civilization today to equate their survival with ours. While the hazard rate of risks is plausibly constant over time, risk is not; it varies over time with the vulnerability and exposure a given society has to a given hazard.

Consider, for example, today’s global food production system, which was recently explored in a modeling study by Moersdorf et al. (2023) (Disclaimer: this is a preprint, which I co-authored). We modeled how the global agricultural system would react to the loss of input like fertilizer, irrigation, mechanization and pesticides by global catastrophic events like a solar storm. Our model finds this would result in yield losses of around 35-50 % globally and would introduce the need for animal based agriculture (in the sense that an animal instead of tractor is used to pull a plough). However, the knowledge of how animal based agriculture is done is mostly lost in place with highly industrialized agriculture like Central Europe. If we cannot simply go back to lower stages of complexity, we would likely just collapse due to a lack of food if no preparations are made. This would be very different for a hunter-gatherer society, as they would not have any vulnerability to solar storms at all, because they lack the technology that could be destroyed by the solar storm.

This specific example can probably be generalized:, it seems likely that a hazard will be more and more destructive, the more connected a civilization is. This is due to the inherent complexity we created, which allows us to be more resilient to smaller shocks, but leads to collapse if our systems are strained beyond their capacity, as we lack the skills to re-introduce older, simpler technologies on short notice.

How low can we go?

If hunter-gatherer societies are too different from our own to be informative, what about more recent societies? Let’s agree 200,000 years is too low and we cannot infer much from the data in deep history for our global society. Another often discussed cut-off is 10,000 years, as this is roughly the time that humans started to form any kind of society with more complexity than a hunter-gatherer group. The next cutoff often discussed is around 250 years ago, when we shifted from a largely agricultural to a largely industrial civilization. Did any of those shift civilization in such a significant way that we cannot do comparisons anymore?

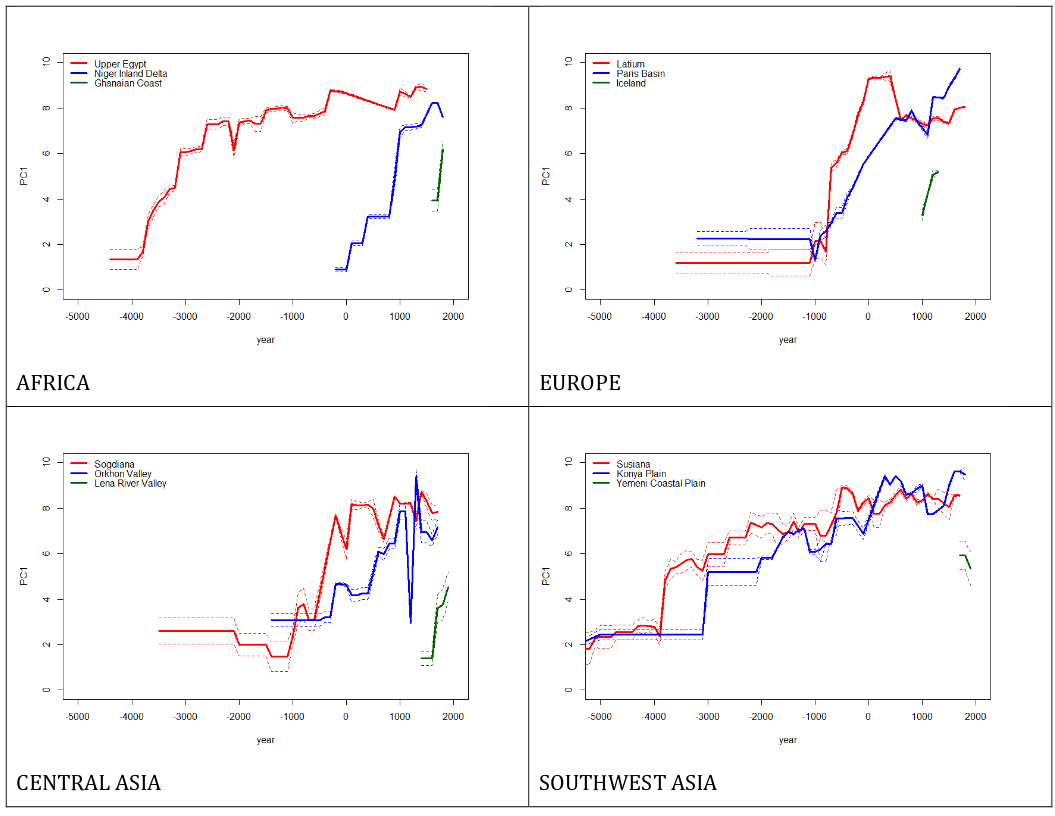

We’ll need some kind of way to compare civilizations across time and space. One way to answer this is looking at the work of Peter Turchin and collaborators with their Seshat database (Turchin et al., 2018). This database quantitatively coded archaeological data from all over the globe which Turchin et al. use to create a measure of societal complexity. This measure is based on 9 variables (e.g. how much writing there is or if money is used) on which they perform a principal component analysis. Principal Component Analysis involves uncovering the primary patterns in data variation. It achieves this by reorienting the data to highlight the directions of greatest variability, enabling the identification of essential underlying structures and simplification of data representation. The resulting new axes, known as principal components, guide our focus toward the essential aspects of the data’s behavior. In Turchin and coauthors’ dataset, the first principal component explains 76 % of the overall variability of their nine measures of societal complexity and all variables contribute equally to it. Turchin and coauthors argue this implies this principal component is a robust measure of overall societal complexity; it’s a single number that captures well the trends in their nine different indicators of societal complexity.

This allows them to plot the complexity for 30 societies over time. Figure 1 shows the timeline for 12 of those societies as an example, but the trend looks somewhat similar for all of the 30 societies considered (Turchin et al., 2018). Unfortunately, their data ends with the industrial revolution. For now, I will assume modern society has comparable complexity, as measured by Turchin and coauthors, as the high levels of the past, as I could not find any study that compares societal complexity before and after the industrial revolution. This assumption is a big one, because when we compare today’s society to the one that existed 200 years ago, they appear to be very different (2).

If you know of important studies I’ve missed here, please email me and I’ll update this article!

Figure 1: Examples for societal complexity over time (Turchin et al., 2018)

The results of Turchin et al. show a trend across regions. Civilizations seem to need around 1000-2000 years to spin up to a high level of complexity. Once reached though, the complexity mostly stays on a stable level. This implies that we can use civilizations as a comparison for today, once it has gone through its complexity spin up period. When this spin-up happens depends on the civilization. For instance, Upper Egypt reached this high complexity around 5000 years ago. For most of the societies considered the spin-up seems to have finished around the year 0. This means that roughly the last 2000 years seem like a reasonable proxy for today for much of the globe. The exception being some places that got complex very early, like Upper Egypt or never got highly complex (according to Turchin’s measure) like the societies in Oceania.

This seemingly similarity in the scale up of different civilizations was also noticed by others. Wand & Hoyer (2024) took a sample of 23 geographic regions from the Seshat dataset and tried to determine if all followed a similar pattern. They find that they indeed do so. Societies tend to need 2500 years to scale up their complexity from early settlements to premodern states. Finding such a clear pattern suggests that we might also find something like this if we look at the last 200 years. However, research here is still scarce.

Understanding how past societies would fare with today’s sustainability measures

So far we’ve argued that, because societies vary in their exposure and vulnerability to hazards, if we want to understand the risks to today’s society, we need to look at societies that are sufficiently similar to today’s and then used a quantitative database of archaeological evidence to try and see when societies become sufficiently like our society. Another way to explore this transferability of human experiences through time is to look at what we think makes today’s society work well and check if past societies also adhered to the same rules. Fortunately, there already exists a massive project where thousands of scientists thought about what makes a current day society sustainable for both people and planet: The Sustainable Development Goals. These goals were formulated by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015 to create a blueprint of what must be done to create peace and prosperity for everyone in the long term. The idea is to formulate a set of goals, which, when archived, allow a sustainable and equal ressources for all humans. The goals include no poverty, zero hunger and gender equality.

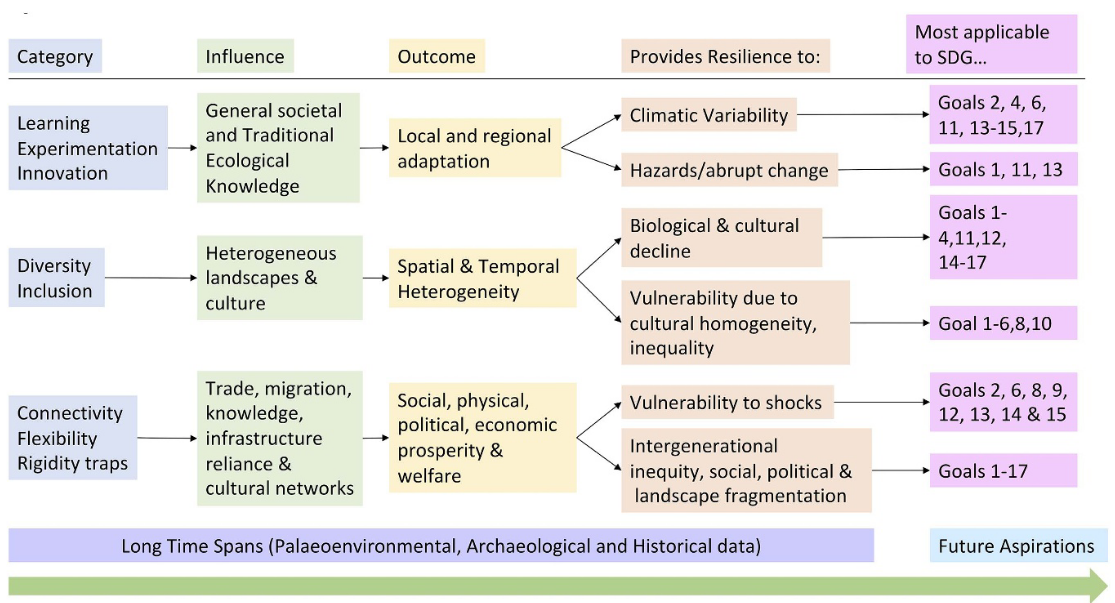

Allen et al. (2022) take the Sustainable Development Goals and look into history to determine if the survival and resilience of past societies is linked to their ability to stay in the ranges that the Sustainable Development Goals aim for. They use past archeological, historical and paleoenvironmental evidence and assign those to equivalent Sustainable Development Goals (Figure 2). For example, the 2nd goal aims to end hunger and achieve food security. This can be measured by looking at the prevalence of undernourishment signs in skeletons. Another example is the 15th goal, which is meant to capture the state of ecosystems on land. It is captured via the amount of deforestation and land degradation.

Figure 2: Schematic showing pathways by which information in historical and archaeological records become relevant to the SDGs (Allen et al., 2022)

Allen et al. determine that, in general, societies in the past that were able to live in line with the Sustainable Development Goals fared better overall. This past validation of today’s sustainable development goals is further evidence that societal insights can be transplanted across time.

The relevance of of premodern history for today

After the above-mentioned papers have explored from what kind of societies we can learn, I also want to discuss a review paper by Haldon et al. (2024), which explored the ways history is relevant for policy makers and especially, how we can make sure to take reliable lessons from the past.

They argue that we rely on history all the time to make political decisions, because if you face a crisis, it is only natural to try to figure out how past decision makers reacted in similar situations. You need something to ground yourself in. However, this runs into several problems. History is complex and policy makers are often stripped for time. This means they tend to cherry pick easily, as they default to the most well known history facts from their own country. However, this leaves out the vast majority of lessons we could take from history. For example, this leaves out lessons from large sample and modelling studies, both of which try to capture the more general trends in history.

Haldon and co-authors also make several suggestions on how we could improve history uptake in politics in the future. They think that especially expert elicitations are underused here. With this they mean to ask a large group of experts about a specific topic, which is relevant to policy and then aggregate all those voices into one report, which highlights the main lessons to be drawn and also in what areas the experts’ opinions diverge from each other. In addition to this, they suggest we should aim for qualitative-quantitative data integration. With this they mean combining the strength of large datasets, with specific case studies. Use the large dataset to identify a recurring trend and then give an example of how this trend played out in a particular historical crisis, which is relevant to what the policy maker is looking for (3). Their hope is that such an approach will make it easier to rely on history for policy makers, as in current debates, the insights of scientists from the natural sciences are often ranked higher in their trustworthiness. It is important for history to bridge this gap, as otherwise many important insights from history will remain unheard in our policy debates.

Conclusion

My reading of the evidence is that studying past societies that have advanced beyond the hunter-gatherer stage and developed for a few thousand years to get to a high level of complexity, can be helpful for understanding our current society. However, this only holds if the industrial revolution did not change our society in such a way which makes it impossible to compare. Whether this is the case is still up to debate. Personally, I am inclined to the notion that meaningful comparisons can still be drawn, particularly when focusing on overarching trends rooted in fundamental human behaviors. This implies that arguments concerning issues like coordination problems, supported by historical data, seem credible to me, as these problems possess a degree of universality that spans across eras. Additionally, the sustainable development goals provide another noteworthy piece of evidence. These goals were formulated with the central question of ensuring the long-term sustainability of modern society. The fact that these goals have also proven beneficial to civilizations of the past can be regarded as a form of independent verification, lending further weight to the idea of parallels between historical and contemporary societal dynamics.

Endnotes

(1) Liu et al. (2018) explain hazard, exposure and vulnerability in the context of existential risk in much more detail.

(2) In principle, the methods used by Turchin and their colleagues to measure complexity can also be used to analyze our current society. For instance, they look at factors like the number of bureaucrats in the government, the size of a society’s territory, and the population of its capital city. Nonetheless, these factors have undergone substantial changes over time, so it’s not certain whether this assumption holds.

(3) This is what the Seshat database is often used for, e.g. in this paper.

How to cite

Jehn, F. U. (2023, August 10). Lessons from the past for our global civilization. Existential Crunch. https://doi.org/10.59350/3fc9m-gvv63

References

- Allen, K., Reide, F., Gouramanis, C., Keenan, B., Stoffel, M., Hu, A., & Ionita, M. (2022). Coupled insights from palaeoenvironmental, historical and archaeological archives to support social-ecological resilience and the Sustainable Development Goals. Environmental Research Letters, 17. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac6967

- Baum, S. D. (2023). Assessing natural global catastrophic risks. Natural Hazards, 115(3), 2699–2719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-022-05660-w

- Haldon, J., Mordechai, L., Dugmore, A., Eisenberg, M., Endfield, G., Izdebski, A., Jackson, R., Kemp, L., Labuhn, I., McGovern, T., Metcalfe, S., Morrison, K., Newfield, T., & Trump, B. (2024). Past Answers to Present Concerns. The Relevance of the Premodern Past for 21st Century Policy Planners: Comments on the State of the Field. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.923

- Liu, H.-Y., Lauta, K. C., & Maas, M. M. (2018). Governing Boring Apocalypses: A new typology of existential vulnerabilities and exposures for existential risk research. Futures, 102, 6–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2018.04.009

- Ord, T. (2020). The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity. Hachette Books, 480 pp.

- Turchin, P., Currie, T. E., Whitehouse, H., François, P., Feeney, K., Mullins, D., Hoyer, D., Collins, C., Grohmann, S., Savage, P., Mendel-Gleason, G., Turner, E., Dupeyron, A., Cioni, E., Reddish, J., Levine, J., Jordan, G., Brandl, E., Williams, A., … Spencer, C. (2018). Quantitative historical analysis uncovers a single dimension of complexity that structures global variation in human social organization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(2), E144–E151. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1708800115

- Wand, T., & Hoyer, D. (2024). The characteristic time scale of cultural evolution. PNAS Nexus, 3(2), pgae009. https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae009