Past societies often found their end amid a challenging climate. Environmental changes can put considerable strain on a society and there are many cases in history where it was a major contributor to their collapse, especially when the change was sudden. Today we are also living through a significant shift in global climate, which makes it likely that we reach temperatures last seen on Earth 20-50 million years ago. While this change is massive, so far it has been relatively slow and predictable. This could change if we start pushing the Earth system more and more out of its old equilibrium and possibly trigger its tipping points.

What are tipping points?

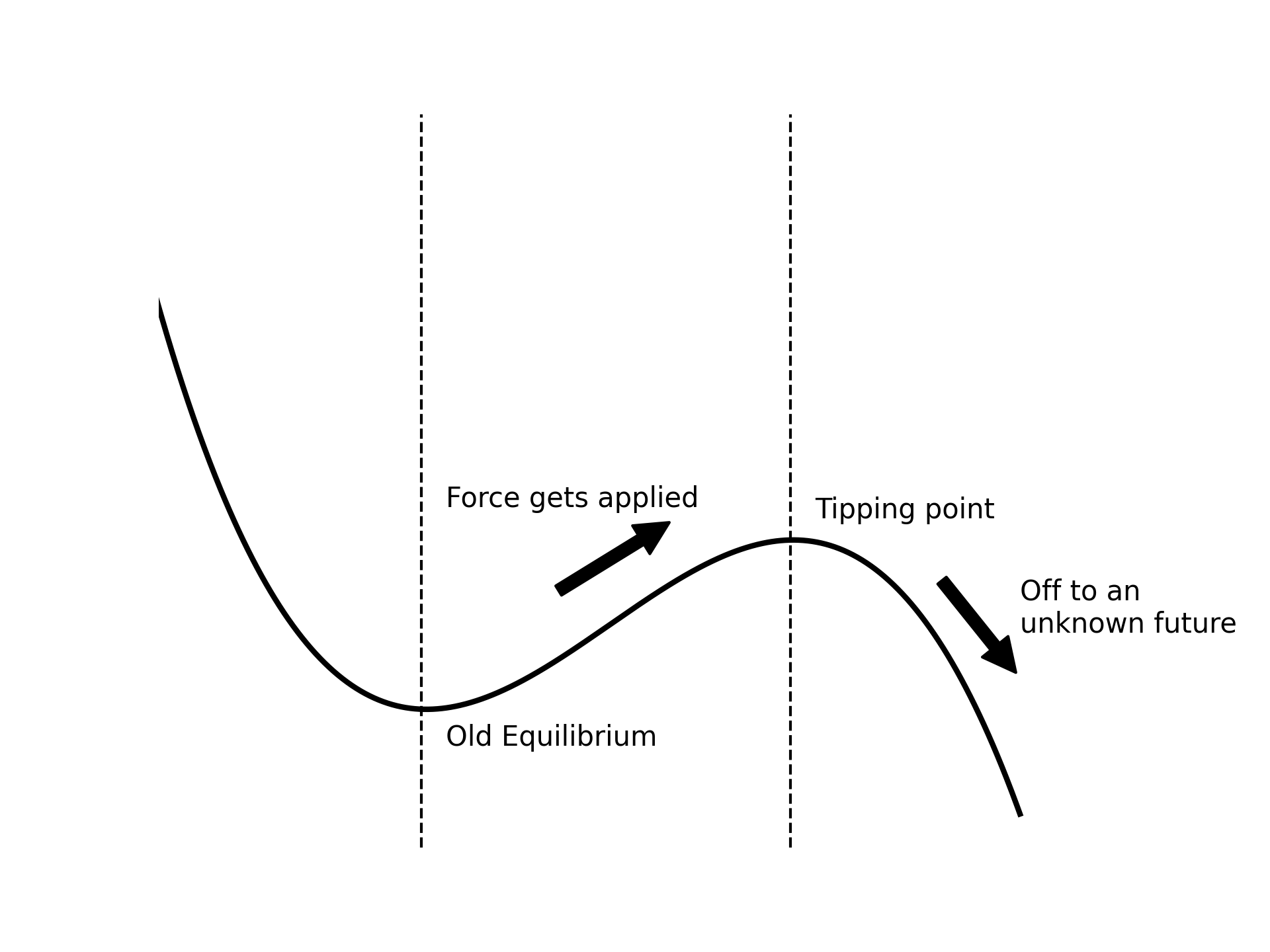

The origin of the idea of tipping points in the climate system is from a 2008 paper by Lenton et al.. Complex systems have a natural ability to bounce back to their original state, so long as they are not pushed too far. A tipping point is a point in the system where any additional pressure will make it impossible to go back to how it was before (Figure 1). Before the tipping points feedbacks in the system tend to bring it back to its original state. Once the tipping point is crossed it won’t.

Figure 1: Schematic presentation of a tipping point. When a system moves away from its previous stable state, it gradually approaches a critical threshold called the tipping point. Once this tipping point is crossed, the system undergoes a significant shift without requiring further external influence and moves towards a new stable state.

Applied to our climate system tipping points can be found in large scale elements of the Earth system like the Amazon rainforest, the Greenland Ice Sheet, or the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. These are called tipping elements. If these tipping elements are pushed beyond their tipping points, this would change Earth permanently. Wang et al. (2023) wrote a very thorough literature review where they describe a variety of tipping elements and the physical processes that govern them. For instance, let’s consider the Greenland Ice Sheet. Currently, it is melting, but we’re unsure if it has reached a critical point of no return. This ice sheet has a significant impact on the local climate through a continuous cycle. It is composed of layers of ice, piling up to heights of 2000-3000 meters. As a result, the air at the top is cooler. Moreover, due to its high albedo, the snow cover of the ice sheet reflects a substantial amount of solar radiation, leading to further cooling. However, when the overall global climate becomes excessively warm, the snow cover starts to melt. This melting process triggers two effects: the sheet’s height decreases, and it becomes darker as the snow cover melts and the exposed ice is darker than the snow. Both of these changes contribute to a rise in local temperature, causing even more ice to melt. Additionally, as the ice sheet melts, the resulting water flows down to the base of the glacier. This water acts as a lubricant, making the glacier move more rapidly. Consequently, these faster-moving glaciers reach the ocean quicker, where they break off as icebergs. In combination, a feedback loop is initiated that cannot be halted until all the ice has melted. In the case of the Greenland Ice Sheet, this scenario could result in an additional sea level increase of approximately 7 meters within the next few thousand years. These changes usually don’t happen abruptly. The term tipping point is used here more in the sense that it is likely that beyond a given point processes are set in motion which will be irreversible for millenia or longer.

The Earth system as a whole likely does not have a single tipping point. Instead it has a complex interaction of separate large tipping elements, who each have individual tipping points. This complex interaction is hard to predict, but entails the risk of a so-called tipping cascade. This means that the tipping elements get in a positive feedback loop and start to push each other outside the safe territory and over their tipping points. The process and problems of tipping cascades are nicely described by Armstrong McKay et al. (2022). The process is similar to the feedback loops for a single tipping element and is mediated by influence on the global temperature and other processes in the climate system. This means if one tipping element like the Greenland Ice Sheet is tipped, it changes the global temperature, while also influencing processes like the salinity of the water in the North Atlantic. This increased temperature and change in salinity in turn could trigger another tipping element, in the case of Greenland Ice Sheet most likely the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, as it strongly depends on salty water in the North Atlantic to keep the circulation going. This self-reinforcing process could theoretically continue until all tipping elements in the Earth system are beyond their tipping point. Armstrong McKay et al. show that such a cascade might even get started in the temperature range of 1.5-2°C. Indeed, some tipping elements could already be beyond their point of no return.

Tipping element interactions

The original study by Lenton et al. identified 15 tipping elements, which they deemed policy relevant. A more recent study by Ripple et al. (2023) used a literature review to identify 41 tipping elements and feedback loops. However, not all of those tipping points are the same magnitude and many of the tipping points identified by Ripple et al. (2023) likely only have little effect on the overall trajectory of the Earth system. Therefore, most papers only focus on a subset.

One interesting study here is by Wunderling et al. (2021). They selected the four tipping points that have been identified as being the most likely to start a tipping cascade: Greenland Ice Sheet, the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the Amazon rainforest. Wunderling and coauthors represent all of the tipping points as a collection of separate differential equations that are all coupled with each other. This coupled model has a collection of parameters that account for the timescale and sensitivity of tipping for each tipping element and the strength of interaction between them. They use a Monte Carlo approach to run the model and show that even in a world with only 2°C warming, we have a 61 % chance that at least one of the major tipping elements will be triggered and in 39 % of the simulations a cascade of two or more tipping elements is started.

Building on this model, the same working group published a follow up study (Wunderling et al., 2023) to assess how much leeway we have when it comes to overshooting the temperatures that might cause tipping. The idea here is that the actual tipping point is characterized not only by temperature, but also by the time you stay in this zone of elevated temperatures. Therefore, to decrease the chance of triggering the tipping point you can either make sure that you keep the temperatures low, or if you fail to do so, you can at least try to get below the threshold quickly. This means the danger zone is a function of how much you overstep the threshold temperature and how long you stay above it.

Their results highlight the need to keep to the 1.5°C aim of the Paris Agreement or, better yet, to keep temperatures below 1.0°C of warming above pre-industrial levels, at least in the long term. In their model, if the long term convergence temperature is 2°C, there is a 82% chance of tipping at least one tipping element, even if the maximum global temperature never rises above 2°C as well. However, that’s the long run, and their results also show that we possibly have considerable time to get back to a lower temperature. For many of the simulations there seems to be a time span of 100-200 years to get back to a lower convergence temperature. That said, this only seems to be true so long as the peak temperature is below 2.5°C. If we go above this temperature, the time we have to get back to lower temperature decreases considerably. This is concerning, as currently our world seems to be aimed at a temperature somewhere between 2 and 3°C of warming.

An earlier modeling study by Ritchie et al. (2021) came to similar conclusions as Wunderling et al., but saw a lower chance of tipping cascades. However, Ritchie et al. did not include direct interactions between tipping elements and only mediates all changes via temperature, while the Wunderling et al. model includes additional interactions based on physical knowledge of how the tipping elements influence each other.

There are a lot of studies that look into tipping elements. However, most of those are focussed on the description of the physical processes and are less focussed on the effects on the climate in combination with other tipping elements (see Wang et al. (2023) for an in-depth description of this). Currently, the studies mentioned here are the main path of research on tipping cascades and how interacting tipping points react to a variety of temperatures.

If you know of important studies I’ve missed, please email me and I’ll update this article!

How could we detect tipping points?

While the occurrence of tipping points is abrupt, there are still tools we can use to detect them before they happen. One paper which explores this is literature review by Dakos et al. (2023). The main way to detect tipping points are so-called Early-Warning Signals. They work by identifying changes in a system’s behavior as it approaches a tipping point. This change is often marked by a phenomenon known as critical slowing down, where the system becomes less resilient to disturbances. This means once a disturbance happens it takes longer and longer to get back to its original state the closer it is to the tipping point. However, Early-Warning Signals do not predict all types of tipping points and can also appear in smoother transitions. Despite this, they have been successful in detecting tipping points in nearly 70% of cases which Dakos and co-authors looked at.

How warm could it get?

Assessing the ultimate temperature impact of tipping points is quite difficult, as the potential ranges of the additional warming caused by them are quite wide. However, we can still make a rough assessment. Armstrong McKay et al. (2022) provides a summary of estimates for the effects of the 15 tipping elements identified by Lenton et al.. If we naively add up all those values we end up with an additional warming of ~1.17°C.

This is quite a lot, but does not tell the whole story, as the tipping elements differ considerably in their likely trigger temperature, whether their contribution to temperatures is positive or negative, and the timescale over which this warming would unfold. If we only add together tipping elements with an estimated trigger temperature below 3°C we end up with ~0.04°C additional warming. If we instead add together tipping elements with an estimated time scale below a hundred years, we have roughly 0.1°C of additional warming. This means that the global effect in the foreseeable future is detectable, but not massive. Still, those changes might be much bigger regionally. For example, the dieback of the Amazon rainforest could happen in as little as 50 years and could increase local temperatures by an additional 2°C . Wang et al. (2023) end up with higher values of ~0.21°C by the end of the century, but only humanity decides to focus mostly on fossil fuels for energy generation.

How bad is our situation?

This is the trillion dollar question and the honest answer might just be: we’re not exactly sure. As hopefully became clear in this post, there is not that much research about what would happen if we started a tipping cascade. However, given paleoclimatic evidence, we do know that the abrupt changes described here can happen. This has been acknowledged in the most recent reports by the IPCC and the overall state of knowledge about this was exhaustively explored in a 2022 literature review by Boers et al.. An example here would be the so-called Dansgaard-Oeschger Events. These events are characterized by a complex interaction of sea ice, atmospheric dynamics and the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation which leads to an abrupt temperature increase of up to 16°C in high northern latitudes in less than ten years. We also have further evidence for past tipping point behavior by looking into our paleoclimatic record. A recent paper by Setty et al. (2023) identified that three past temperature peaks in the Earth’s system are linked to significant changes in the carbon cycle. This indicates that a large amount of carbon dioxide was added to the atmosphere in a short period of time. Likely this was caused by a self-reinforcing loop of warmer temperatures and higher methane and carbon dioxide release from peatlands, submarine hydrates and permafrost.

There have been calls for more research into this area and higher temperature climate change in general (see for example Kemp et al. (2022)) and there are also calls for creating a special report of the IPCC about exactly this topic (Boers et al., 2022). But at the moment, this research has yet to be produced and summarized. Wang et al. (2023) also highlights several times that many of the processes are not well understood, especially for time scales beyond 2100. This research could be challenging, as tipping points are not considered in most of the major models used to model climate change (Kemp et al., 2022). It’s not even clear whether the global climate models we use are even up to that task (Balaji et al., 2022). Boerst et al. highlight several times that most of our current models struggle to replicate abrupt transitions in our paleoclimatic record, due to a stability bias and insufficient spatial resolution. This means it is hard to trigger extreme events, even if you apply massive forcing. However, when it comes to tipping points, extreme events are exactly the thing we want to study.

Still, my conclusion from writing this is a grim optimism. Don’t get me wrong, triggering any of the tipping points is very bad. I think it would be a monument to our failure if we destroyed the great biodiversity in the Amazon rainforest. However, it seems like tipping points cannot easily contribute an additional amount of warming that would put Earth as a whole on a >3°C trajectory, at least in the next hundred years. Also, many of the biggest impacts will be felt regionally, not globally. Finally, the biggest impacts of the tipping points will be to the general functioning of the biosphere and not to the temperature directly. This means my optimism is more in the form that I now think that tipping points alone are unlikely to cause a collapse of global civilization due to temperature changes. Still, we should be careful, as many of the past abrupt transitions in climate are not well understood and the Earth system might have some unwelcome surprises for us in store.

How to cite

Jehn, F. U. (2023, June 19). The trouble with tipping points. Existential Crunch. https://doi.org/10.59350/b9pgp-6ae83

References

- Armstrong McKay, D. I., Staal, A., Abrams, J. F., Winkelmann, R., Sakschewski, B., Loriani, S., Fetzer, I., Cornell, S. E., Rockström, J., & Lenton, T. M. (2022). Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points. Science, 377(6611), eabn7950. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn7950

- Balaji, V., Couvreux, F., Deshayes, J., Gautrais, J., Hourdin, F., & Rio, C. (2022). Are general circulation models obsolete? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(47), e2202075119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2202075119

- Boers, N., Ghil, M., & Stocker, T. F. (2022). Theoretical and paleoclimatic evidence for abrupt transitions in the Earth system. Environmental Research Letters, 17(9), 093006. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac8944

- Dakos, V., Boulton, C. A., Buxton, J. E., Abrams, J. F., Armstrong McKay, D. I., Bathiany, S., Blaschke, L., Boers, N., Dylewsky, D., López-Martínez, C., Parry, I., Ritchie, P., van der Bolt, B., van der Laan, L., Weinans, E., & Kéfi, S. (2023). Tipping Point Detection and Early-Warnings in climate, ecological, and human systems. EGUsphere, 1–35. https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2023-1773

- Kemp, L., Xu, C., Depledge, J., Ebi, K. L., Gibbins, G., Kohler, T. A., Rockström, J., Scheffer, M., Schellnhuber, H. J., Steffen, W., & Lenton, T. M. (2022). Climate Endgame: Exploring catastrophic climate change scenarios. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(34), e2108146119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2108146119

- Lenton, T. M., Held, H., Kriegler, E., Hall, J. W., Lucht, W., Rahmstorf, S., & Schellnhuber, H. J. (2008). Tipping elements in the Earth’s climate system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(6), 1786–1793. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0705414105

- Ripple, W. J., Wolf, C., Lenton, T. M., Gregg, J. W., Natali, S. M., Duffy, P. B., Rockström, J., & Schellnhuber, H. J. (2023). Many risky feedback loops amplify the need for climate action. One Earth, 6(2), 86–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2023.01.004

- Ritchie, P. D. L., Clarke, J. J., Cox, P. M., & Huntingford, C. (2021). Overshooting tipping point thresholds in a changing climate. Nature, 592(7855), 517–523. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03263-2

- Setty, S., Cramwinckel, M. J., van Nes, E. H., van de Leemput, I. A., Dijkstra, H. A., Lourens, L. J., Scheffer, M., & Sluijs, A. (2023). Loss of Earth system resilience during early Eocene transient global warming events. Science Advances, 9(14), eade5466. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ade5466

- Wang, S., Foster, A., Lenz, E. A., Kessler, J. D., Stroeve, J. C., Anderson, L. O., Turetsky, M., Betts, R., Zou, S., Liu, W., Boos, W. R., & Hausfather, Z. (2023). Mechanisms and Impacts of Earth System Tipping Elements. Reviews of Geophysics, 61(1), e2021RG000757. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021RG000757

- Wunderling, N., Donges, J. F., Kurths, J., & Winkelmann, R. (2021). Interacting tipping elements increase risk of climate domino effects under global warming. Earth System Dynamics, 12(2), 601–619. https://doi.org/10.5194/esd-12-601-2021

- Wunderling, N., Winkelmann, R., Rockström, J., Loriani, S., Armstrong McKay, D. I., Ritchie, P. D. L., Sakschewski, B., & Donges, J. F. (2023). Global warming overshoots increase risks of climate tipping cascades in a network model. Nature Climate Change, 13(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01545-9