Almost all researchers use “gap-spotting”, a process that only creates boring research questions

It usually does not happen that I read through a non-fiction book in two days, but I could not put this one down. In the recent months, I noticed that one thing that I have to improve to become a better researcher is to come up with more and better research questions. However, when I looked around, I could not find many resources about this that offer more than uninspired check lists. By chance, I stumbled on “Constructing Research Questions: Doing Interesting Research” by Mats Alvesson and Jörgen Sandberg, and I am glad I did.

This book tells its stories somewhat in parallel, but there are four main topics the authors are exploring:

- How can we classify research questions?

- Almost all researchers use “gap-spotting”, a process that only creates boring research questions

- How can we find more relevant research questions? Challenge assumptions instead!

- Why do scientists use gap-spotting so much, even though it produces more boring research?

The focus of the book is on social science. However, in my experience in a collection of other research fields, those problems are also acute in fields far from social science. Therefore, I’ll treat everything here as a general comment around science. However, I would be curious to hear if there are fields in science that don’t suffer from the problems explained here.

I think the classification of research questions is the least interesting part of the book (still interesting though), so I’ll skip it and focus on the spicy parts instead.

Alright, let’s go through this step by step.

Almost all researchers use “gap-spotting”, a process that only creates boring research questions

The main claim this story starts with is that we have more research now than ever, but interesting and influential papers have gotten less, not more. This has to have a reason, and the authors propose that researchers today are mainly relying on gap-spotting to find research questions. Gap-spotting means that the researchers start their papers by identifying a gap somewhere in the scientific literature, and then justify the existence of their study by claiming that it fills the gap they found. Alvesson and Sandberg back this up with an empirical study. They collected a sample of over 100 papers and scrutinized them for their justification of the research question. Almost all of them used gap-spotting! They also found that gap-spotting comes in different flavors:

- Confusion spotting: “The literature has competing explanations for X, and my study will show which one is right.”

- Neglect spotting: “There is no good research about X. My study fills this hole.”

- Application spotting: “Technique X might be great to use on Y and I have tested it.”

After reading those descriptions of how gap spotting happens, you probably feel called out. At least I did. Most of the research I have written so far employs those themes to explain why I use a specific research question. And when I look around, the people I know also explain their research this way. It is often even the way people get taught to find research questions in the first place.

Alright, we now know that gap-spotting is the most common way to come up with research questions. However, there are also other ways:

- Critical confrontation: “X is crap and I will tell you why.”

- New idea: “X is new and great and I will tell you all about it.”

- Problematization: “I challenge X by showing that its underlying assumptions are not true and present a new set of assumptions that better explain X or even show that X is not a useful concept/theory/idea in general.”

The prevalence of using gap-spotting becomes a problem if the resulting research questions aren’t relevant and interesting. This might seem subjective, but we can actually find properties that important and influential studies have in common. Scientists evaluate a study as relevant and interesting if it challenges the assumptions of an established theory. Studies that do this have higher citations counts in comparison with studies that don’t. The problem is: Gap-spotting produces incremental additions at best, and has a good chance of just filling gaps in the literature no one even cares about. If I look for a gap to fill in the current paradigm, it is unlikely that the resulting study will challenge the paradigm itself.

We see that most studies use gap-spotting, and gap-spotting produces mostly studies that other academics don’t find that interesting. But is there a better way that we should use instead? According to Alvesson and Sandberg there is: Problematization!

How can we find more relevant research questions? Challenge assumptions instead!

Before even discussing how to find better research questions, the authors hammer in one point again and again: You have to read more! If you think you are reading enough, read more! If you think you read too much, you don’t, read more instead. Knowing and understanding the literature is the foundation of finding new research questions. Without this solid foundation, it does not matter what your process in finding questions is, you’ll produce nothing worthwhile either way. This does not mean that you have to read every obscure paper you could possibly find. Instead, concentrate on the most important works in your sub-field, but also read in neighboring or even distant fields. This allows you to gain new perspectives, and those will come in handy when it comes to finding the actual research questions.

As we have seen above, problematization focuses on challenging the underlying assumptions of established theories. To be able to do this, Alvesson and Sandberg propose a series of steps to apply problematization. They emphasize that this is not meant to be a linear process. Instead, you will have to revisit each step to come up with interesting and relevant research questions. The steps are:

-

Identifying a domain of literature: The key here is to find the most influential studies in the topic you are interested in. They contain the most important assumptions. However, you have to be up to date on the surrounding literature as well to make sure that the assumptions have not already been challenged by someone else.

-

Identify and articulate the assumptions: Usually, the assumptions aren’t laid out clearly, so we have to dig them up. Also, assumptions come on different scales. This can range from the shared assumptions on what a certain method can do, to the foundational assumptions of a whole field of research. The larger the assumption we want to dig up, the further we have to step away from the field. This gives us the distance and perspective needed to find the assumptions. Here it helps to have broad knowledge about other fields, as this highlights how concepts could be defined differently and shines a spotlight on the underlying assumptions.

-

Evaluate the articulated assumptions: Once you have identified the assumptions, it is time to articulate them in detail. You know that you have found the right assumptions to challenge if other researchers tell you “That’s interesting!” if you discuss the assumptions with them. In this step, you also have to decide which of the assumptions you found you want to interrogate further. Things to keep in mind here are a) the scope (bigger is better), b) can you come up with alternative assumptions, c) how important is the challenge of this assumption for society?

-

Develop alternative assumptions: Once you have decided on assumptions you want to challenge, you have to find alternative assumptions that are better at explaining the world. The important thing here is that you have to be truly open to new assumptions. You want to avoid reproducing your own biases. This can be helped by a) reading sources outside of the field, b) simply reversing the original assumptions, c) talking with people who hold assumptions that are different to yours.

-

Relate assumptions to the audience: Before you challenge assumptions, you have to check that people even hold them. Would be kind of a bummer if you challenged assumptions that nobody has. Also, you have to consider what the effects on the audience and society could be if the assumptions are successfully challenged.

-

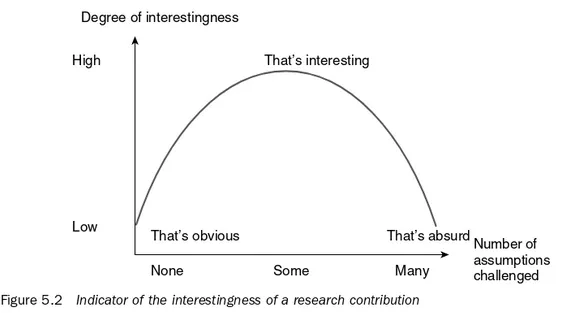

Evaluate the alternative assumptions you came up with in its totality: Once you completed the first 5 steps, you have to check where your collection of alternative assumptions ends up on this graph:

If you challenge too few assumptions, people will discard it as obvious, but if you challenge too many, people will feel like you are proving too much and will just see it as absurd. You want the sweet spot where people read your alternative assumptions and their first reaction is: “That’s interesting!”.

Example

Now let’s look at a short example of this. It isn’t fully developed, as this would be a big academic project in its own right, but is merely meant to exemplify the process:

- Identifying a domain of literature: One path defining study for the field of progress studies is: “Are ideas getting harder to find?” by Bloom et al. (2020). It shows that we are having less and fewer ideas per unit of resources we put into science.

- Identify and articulate the assumptions: The key assumption in this study (and in progress studies more generally) is: We are having fewer ideas, because ideas get harder to find the further we explore science.

- Evaluating articulated assumptions: If this assumption could be successfully challenged it would be on a big scale and also relevant for society, as it would be pretty impactful if we could simply find a way to have more ideas per unit of research input again.

- Developing an alternative assumption ground: The book this review is about offers an alternative explanation for the problem that we have fewer ideas per unit of research input. Maybe the real reason is that gap-spotting was way less common in the past and the pace of research only slowed down because researchers rely on gap-spotting more and more, which leads them to less relevant research questions.

- Relate assumptions to the audience: I haven’t really done this step, as this is only an example. However, I am reasonably confident that people in the field of progress studies hold the assumption mentioned above and would tell me so if I would talk to them about it.

- Evaluate the alternative assumptions you came up with in its totality: I am fairly optimistic that this alternative assumption would end up in the “That’s interesting!” region. It does not challenge too much to become absurd, but it challenges such a fundamental assumption in progress studies, that it is unlikely to be seen as obvious.

Why do scientists use gap-spotting so much, even though it produces more boring research?

We have seen that much of research is done ineffectively, even though promising alternatives are available. This is especially confusing as there is clear evidence that assumption challenging studies are cited more and are widely regarded as more interesting and impactful than gap-spotting research. Why don’t researchers focus on producing such impactful research? Alvesson and Sandberg propose some possible explanations:

Institutional conditions

Scientists are more and more evaluated on having published research in high impact journals. Journals tend to emphasize the need to make clear in what way the study you submit adds to the current science. This means that it is likely more difficult to publish studies that challenge dearly held assumptions. As scientists need to publish to further their career, they focus on the easier gap-spotting research.

Professional norms in academia

Scientists are concentrated more and more in very tiny sub-fields. However, if you are deep in a specific sub-field, it becomes more unlikely that you will produce paradigm breaking research on a large scale. Also, research that is relevant for society often moves across disciplines. This is harder to do for someone who only knows about a niche topic. An additional point Alvesson and Sandberg criticize is that authors usually have to implement all the changes reviewers propose. This leads the authors to try to minimize the possible points of criticism in their draft. Challenging an important assumption can easily be criticized and is thus left out.

Personality of the researcher

Gap-spotting has become more entrenched over time. Many people know it as the only way to come up with new research questions. This might lead to them thinking that this is the only proper way to do science and other approaches should be opposed.

Call to Action

The book ends with a call to action for all researchers. While we could interpret the current situation of scientists being trapped in a system that forces them to do uncreative research, we could also look at academia and see that all the decisions are made by researchers themselves. Who reviews papers? Researchers. Who makes editorial decisions? Researchers. Who decides which projects get funded? Researchers. Who decides which research question to follow? Researchers.

We ourselves are creating this system, so we are the people who have to break free from it. Stop focusing only on papers, there are other important academic contributions as well. Reject more papers if they only fill gaps nobody cares about. Emphasize to younger scientists that it is important to study questions that go beyond filling gaps. Broaden your horizon to be able to do interdisciplinary work.

Become an innovative researcher, not for your career, but because it is the right thing to do.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Ekaterina Ilin and Peter Ruschhaupt for valuable feedback on this post.

How to cite

Jehn, F. U. (2023, February 3). Against the dominance of gap-spotting in research. Existential Crunch. https://doi.org/10.59350/cwhhx-cp072